When we learned this week that the brutal murder of a Perthshire woman nearly 150 years ago is Scotland’s oldest unsolved killing, it got The Courier’s online team wondering — just how did our papers report the crime all those years ago?

As Kirsten Johnson reported on Thursday, Tayside Police have revealed that — at least officially — the file on Janet Henderson’s mysterious death at Mount Stewart Farm, near Forgandenny, on March 30, 1866, has never been closed.

The 50-year-old’s mutilated body was discovered lying in a pool of blood in the kitchen of her brother William Henderson’s home, sparking a nationwide murder hunt.

The wife of Airntully labourer James Rodgers, Janet had been helping out at the farm while her brother sought new servants in Perth.

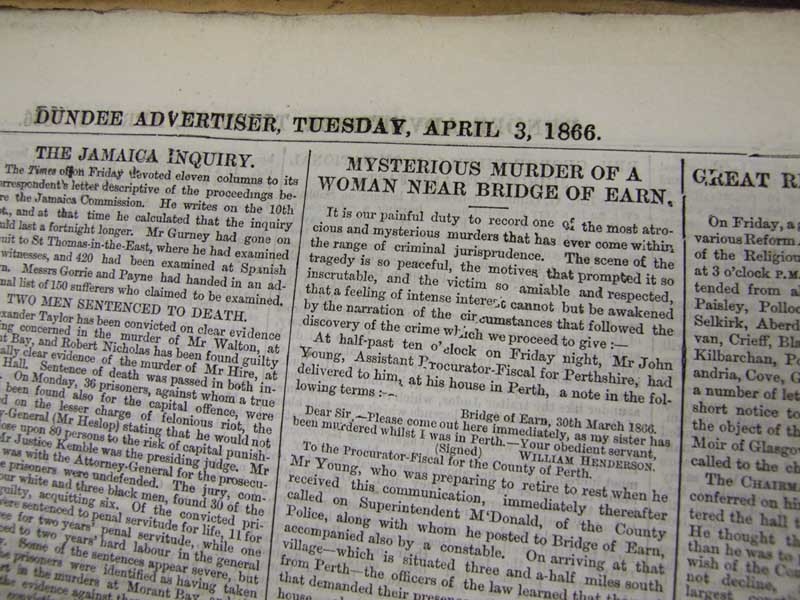

But as The Dundee Advertiser revealed in its edition of April 3, 1866, neither James nor William would ever again see her alive.

In an article headlined “MYSTERIOUS MURDER OF A WOMAN NEAR BRIDGE OF EARN” The Advertiser warns the reader:

“It is our painful duty to record one of the most atrocious and mysterious murders that has ever come within the range of criminal jurisprudence.”

In the colourful writing characteristic of 19th century journalism, it continues:

“The scene of the tragedy is so peaceful, the motives that prompted it so inscrutable, and the victim so amiable and respected, that a feeling of intense interest cannot but be awakened by the narration of the circumstances that followed the discovery of the crime which we proceed to give…”

We learn that “at half-past ten o’clock on Friday night” the assistant procurator fiscal of Perthshire, John Young, receives at his home in Perth a letter from William Henderson.

In a strikingly polite manner considering the circumstances, Henderson writes:

“Dear Sir, — Please come out here immediately, as my sister has been murdered whilst I was in Perth. Your obediant servant WILLIAM HENDERSON.”

Young rounds up a Superintendent McDonald and a constable of the County Police and, after establishing the exact location of the crime:

“Thither they at once proceeded, where a terrible spectacle presented itself.”

Sparing no detail, the report reveals that Janet:

“…lay on her back on the kitchen floor, a murdered corpse. A fearful contusion of the right ear, and a large wound on the top of the head by which the skull had been crushed in, and a heavy axe close by, showed too clearly how the foul act had been perpetrated. The head of the body weltered in blood, and lay towards the door, while the feet were extended in the direction of the fire. A great portion of the floor was covered with blood, which also bespattered many articles around. The house had a confused and disordered appearance, as if it has been ransacked for plunder.”

Now, at this point, we, and perhaps you, are starting to have suspicions about William Henderson. The first to find the body… The first to report the murder… That oddly calm letter to the assistant procurator… His claim to have been in Perth when it happened… Could he have been responsible for this “horrid crime”?

Once again, The Advertiser leaves no stone unturned and no angle ignored.

“For a considerable time back Mr Henderson has lived alone, without any servant or attendant; but on Wednesday last his sister … took up residence with him at his request, for the purpose of cleaning his house and attending a cow that was daily expected to calve. On the forenoon of the day in question, Mr Henderson states he left home for Perth with a horse and cart at eleven o’clock, leaving his sister alive and well. On his return home, between six and seven in the evening, he was surprised to find both the back and front doors of the house locked, and also the shutters of the windows secured. Having knocked in vain for admittance, he had recourse to entering the house by a ladder at one of the windows of the second storey, when he was horrified to find that his sister had been foully deprived of life during his absence.”

But, for The Advertiser, any suspicion surrounding Henderson stops there.

Referring to his account, it declares:

“This statement, it is of consequence to mention, has received material corroboration. It has been proved beyond all doubt that Mr Henderson was in Perth in the course of Friday, and also, that on his way home he made business calls on two tradesmen at Bridge of Earn, between six and seven in the evening.”

There are no such assurances given for Henderson’s foreman James Crichton, however.

In a sentence dripping with innuendo, the article states:

“The man Crichton was ploughing in the neighbourhood at the time, but can give no information on the subject.”

Newspapers across the UK initially carried descriptions of a “tramp” reportedly seen leaving the scene around the time of the murder and a £100 reward was offered to anyone who could offer information that might lead to a conviction.

Crichton was subsequently charged with murder — but following a trial at Perth the following year the case was found not proven and Crichton was released.

And so a crime that shocked 19th century Scotland gradually faded to memory.

The Advertiser and its successor The Courier & Advertiser will have made reference from time to time. But as the years passed and any possible witnesses died, the “atrocious and mysterious” murder near Forgandenny was to become what it is today — Scotland’s oldest unsolved killing.

Police forces across Scotland are currently investigating 77 unsolved murders — 53 in the Strathclyde region, 10 in Tayside, six in Lothian and Borders, four in Grampian, three in the Northern Constabulary area and one in Fife.

Most forces only have records dating back to 1975, when the current force structure was established.

But Scotland’s newspapers, in their various guises, have been around much, much longer. So perhaps the answers to these crimes lie waiting to be discovered in the dusty files that fill the shelves of publishers like D. C. Thomson.

It would be a fitting legacy to the generations of journalists, printers and readers who have helped investigate and document our nation’s affairs and lay down a priceless historical archive for future generations to explore.