Computers might seem like a relatively recent invention, but their history stretches back more than 2500 years to the abacus.

The difference between a basic bean counting machine and a modern computer might seem vast, but the basic aim to make repeated calculations more quickly than the human brain, is identical.

The Second World War was a crucial time for the development of computers and by 1965 the concept of a home computer was still the stuff of science fiction.

And yet significant leaps were being made in computer technology which paved the way for the technological world we take for granted today.

Perhaps not surprisingly, one forward-thinking institution, already renowned for its collective brainpower, was St Andrews University.

In 1965 the university brought its first computer into service in the town.

And now it is putting on a small exhibition at the Byre Theatre charting the changes in this now ubiquitous technology.

The IBM 1620 Model II was the largest system of its kind in Europe and it occupied an entire air-conditioned room within the university’s observatory.

Valued at £135,000 in 1965 but purchased for £60,000, it cost around the same as a small housing estate at the time when the average UK house price was £3,660.

The enormous machine, which was the result of more than a year of negotiations and planning, was run around the clock, managed by the Department of Astronomy and trained operators.

While the capacity of the IBM 1620 is minute by modern standards, the computer was advanced for the time and played an important role in the development of computing in St Andrews.

Records from the time show that the computer was in use over 400 hours per month. Courses were held on programming and seminars were given by university staff who had made use of results from the computer.

It was able to churn through extensive calculations and was most in demand by staff and researchers studying astronomy, applied mathematics, botany, chemistry, physics and theoretical physics.

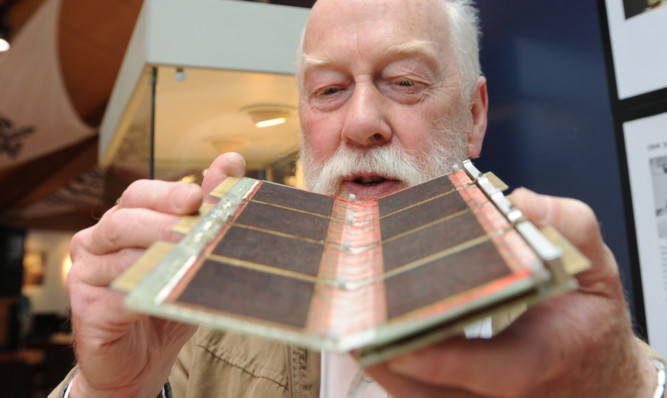

Peter Adamson, retired computing officer from IT Services at St Andrews University, has worked with Roger Stapleton, honorary scientific officer from the School of Physics and Astronomy, to gather together items for the Byre Theatre display.

These include elements from the first computer and its early successors like the BBC Micro and Commodore PET, along with documents such as the 1961 letter from the late Professor Douglas Walter Noble Stibbs to the then Principal, Sir Thomas Malcolm Knox, putting forward the case for purchasing the 1620.

An array of objects and images from the 1960s and early 1970s show what life was like in what was then called the Computing Laboratory, including heavy hand-cranked calculators, a large steel printer roller covered in embossed symbols and lettering, and early punched cards, which served to input programs or data into the computer.

Mr Adamson, 68, who retired from the university’s IT Services department in 2011 after 42 years, told The Courier that the first computer service within St Andrews revolutionised departmental work.

He said: “There were demands from certain departments for processing large quantities of data. Obvious candidates were the physics and astronomy departments. We had astronomers having to use the IBM central computer in London, carrying their data reams with them, with great expense involved.

“A computer at St Andrews was talked about as early as 1955. But I must correct a mistaken assumption. This was not the first computer at the University of St Andrews. At that time, Queen’s College in Dundee was part of St Andrews University and they got their first computer in 1961.”

Mr Adamson said the St Andrews computer was so big because the components were so big. From the processors that did calculations to the memory. Nowadays a silicon chip contains millions of transistors. But in those days one transistor came in a metal can which would then be placed on a circuit board. Power supplies and air conditioning units also took up vast space, as did the tapes and discs.

He added: “The equipment required careful programming and weekly engineering maintenance but we were now able to process enormous amounts of data locally instead of taking it elsewhere.

“I have fond memories of working with these early computers, and of course I enjoyed it when enterprising users made the IBM 1620 graph-plotter hum Christmas carols, or created a 3D noughts and crosses game. Due to a bug, the computer always won!”

Swift advances in technology and increasing workload meant that a replacement computer was installed in 1969.

This IBM 360/44 was specially tailored for scientific use.

It enabled computer programs to run 60 times faster than the 1620 model, and it had a central processor with a respectable 128K bytes of memory dwarfed by today’s smart phones.

The free exhibition, The First Computers in St Andrews, runs at the Byre Theatre in St Andrews until October 31.