Scotland has the strongest wildlife legislation in the UK. And yet the difficulties securing wildlife crime prosecutions remain very real, according to retired Tayside police officer Alan Stewart, who was Scotland’s first full-time wildlife crime officer.

Between April 2014 and February 2015, almost 250 wildlife crimes were recorded by Police Scotland.

The research, published by the Scottish Environment Link charity, showed that only 20 (13.5%) of the 148 confirmed wildlife crimes reported to the police during 2008-2013 resulted in a prosecution.

This led environmental groups to claim wildlife crime in Scotland is being under reported, whilst the Crown dismissed the charity’s criticism as “inaccurate”.

In an interview at his home in the Perthshire village of Methven, Mr Stewart said the approach to tackling wildlife crime is now far superior to decades ago when police were “just not very good at it”. The best deterrent was the likelihood of being caught and the prospect of jail.

But he said proving a wildlife crime had been committed particularly in remote areas continued being a huge challenge.

He told The Courier: “I suppose you could say wildlife crime is becoming a wee bit less of a problem because we’ve raised awareness of it so much over the past decade that people know what to look for, and how to report it to the police.

“But I’ve always said that of all the things I’ve investigated over the years, wildlife crime was the most difficult. Especially for wildlife crime that takes place in the middle of nowhere. If it’s someone knocking a house martins nest off a house that’s quite simple. But if it’s a poisoned golden eagle on an estate with nine gamekeepers, first of all you’ve to prove it’s a gamekeeper. Then you’ve got to prove which one. It’s very difficult.”

Mr Stewart has written four books about wildlife crime over the past decade. He also starred in the 2007 BBC documentary Wildlife Detectives about the work of wildlife officers in Scotland.

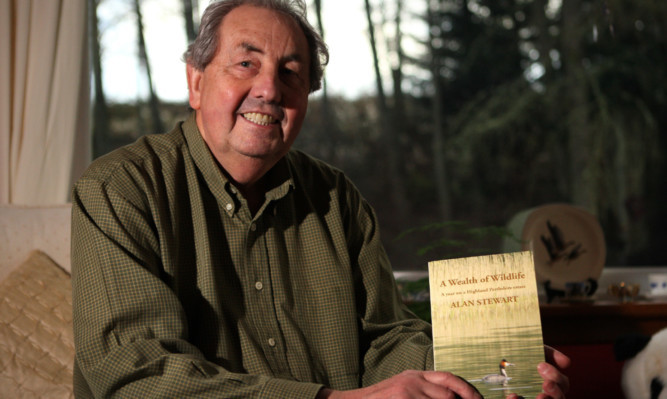

It’s his love of ecology and the impact of wildlife crime which has inspired his latest book, ‘A Wealth of Wildlife: A year on a Highland Perthshire estate’.

“The book is done in diary form,”he said. “I’m walking around the anonymous estate every day doing about eight or 10 miles, on a different route. I relate to the reader the different things that I’m seeing and expand on them. Sometimes it’s as far as wildlife crime is concerned and sometimes about the natural history, the ecology. “

Born in Perth, Mr Stewart, now 68, is a former pupil of Craigie School and Perth High School. He started as a police cadet in 1964, spending time as a constable in Dunblane and Perth. He spent a significant part of his career in CID and with the drugs squad. He was promoted to inspector in 1993, covering Crieff and Kinross, and retired after 31.5 years police service in 1997.

During his last four years with the force, he was Tayside police’s first dedicated wildlife crime officer.

He was re-employed as a civilian full-time wildlife crime co-ordinator a role he held until 2011 and also served as intelligence officer with the Livingston-based National Wildlife Crime Unit.

He investigated everything from bird of prey persecutions, to illegal trapping, poisoning, shooting, and poaching of salmon, game and deer.

The highest profile case he investigated was the poisoned golden eagle found at Millden estate in Angus in 2008.

Mr Stewart said it was another example of a case where a prosecution was never secured. Shaking his head, he added: “We had to prove it was killed on that estate. If it was killed on that estate was it one of the gamekeepers? Although we made considerable enquiries there was no satisfactory outcome. “

He first got involved in wildlife crime investigations as a young officer in the 1960s when he specialised in poaching cases. It was an experience that stood him in good stead.

He added: “There was a lot on the go at that time at three locations – on the Tay down at the (Perth) harbour where the Almond comes into the Tay and on the River Almond itself. I had some very good informants who, as well as telling me about general crime – they were salmon poachers themselves – would tell me about salmon poaching incidents. I suppose from their point of view it suited them, because they would tell me about a poaching incident that was coming off in a particular river at a particular time, involving particular people. They knew then I’d be there and they’d be fairly safe elsewhere!

“It was of mutual benefit!” he laughed.

Alan helped secure the first conviction under the Protection of Wild Mammals Scotland Act 2002.

It involved a man coursing foxes at the beach at Broughty Ferry.

He added: “Tayside was a great area to work in as a wildlife crime officer. It had it all.”