The world’s largest ice sheet could be more vulnerable to the effects of climate change than previously thought, according to new research.

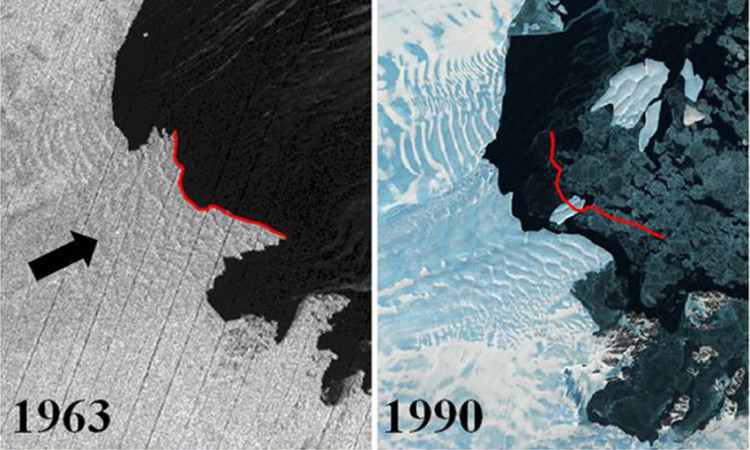

Scientists used 50 years of declassified spy satellite imagery from 1963 to 2012 to create the first long-term record of changes in glaciers where they meet the sea along 3,355 miles of the East Antarctic ice sheet’s coastline.

The sheet holds the vast majority of the world’s ice and enough to raise global sea levels by more than 164ft.

Using measurements from 175 glaciers, the researchers from the Geography department of Durham University were able to show the glaciers underwent rapid periods of advance and retreat which coincided with cooling and warming.

The team said this suggested large parts of the ice sheet, which reaches thicknesses of more than 2.5 miles, could be more susceptible to changes in air temperatures and sea ice than was originally believed.

Scientific opinion suggests glaciers in East Antarctica are at less risk from climate change than areas such as Greenland or West Antarctica due to its extremely cold temperatures, which can fall below -30C (-22F) at the coast and even colder inland.

However, the Durham team said there was now an urgent need to understand the vulnerability of the East Antarctic ice sheet.

Dr Chris Stokes said: “When it was warm and the sea ice decreased, most glaciers retreated but when it was cooler and the sea-ice increased, the glaciers advanced.

“In many ways, these measurements of terminus change are like canaries in a mine they don’t give us all the information we would like but they are worth taking notice of.”

The researchers found in the 1970s and 80s, temperatures were rising and most glaciers retreated but during the 1990s, temperatures decreased and most glaciers advanced

The 2000s saw temperatures increase and then decrease, leading to a more even mix of retreat and advance Dr Stokes said: “If the climate is going to warm in the future, our study shows large parts of the margins of the East Antarctic ice sheet are vulnerable to the kinds of changes which are worrying us in Greenland and West Antarctica.”