As the 70th anniversary of D-Day approaches, Courier Farming looks at the significance the momentous events had for agriculture.

Many a farmer listening to reports of the day’s events on old Bakelite radios would already have felt the impact of the preparations for the landings.

Farming was as important a front as the military ones in Europe, North Africa or the Far East. British agriculture had been given a huge task to provide sustenance for the population as well as the armed forces following the virtual cessation of food imports.

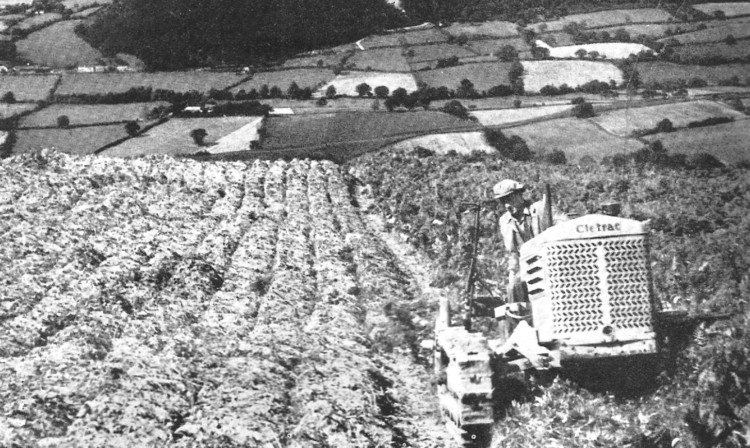

Agriculture rose to the task magnificently, and part of the success was due to the increase in mechanisation and the use of tractors in particular.

In six years of war the number of tractors tripled to around 150,000 machines, most of which were the Fordson Standards.

Some of this increase came about in the rise of home production and the decline of exports: 913,731 tractors and items of machinery were exported in 1939, compared to 144,936 units in 1940.

Significant numbers of North American tractors began to arrive following the Lend-Lease agreement signed in 1941.

But as early as 1942 when the Allies began building up forces, supplies and equipment in preparation for D-Day Lend-Lease agricultural imports actually dropped, while demand from agriculture was still increasing.

The huge military supplies needed for an invasion were parked throughout southern Britain in readiness for the assault and led to Britain being described as the largest American aircraft carrier.

Much of this equipment was parked in the countryside of southern England.

However, activity relating to the D-Day landings did spread north, with increased air activity, train traffic and military training at bases such as the Commando training centre at Achnacarry.

Farming folk of the south west would see the components of Churchill’s inspired Mulberry harbours constructed at Garlieston in Wigtownshire.

Country folk could see at first-hand the build-up of men and munitions, especially US troops, billeted in individual households.

Indeed some large tracts of land, including farms and even whole villages in Devon, were cleared of local inhabitants to create training grounds for US forces.

Some of the deep hedge-lined lanes in this part of the world were completely covered with camouflage nets to hide the military vehicles that were parked in them.

Even haystacks were used to hide equipment.

Such was the subterfuge to confuse the enemy as to where the landings would take place that the allies created a phoney army based in Kent to create the illusion of landings in the Calais area.

Tank tracks were created in fields to create the illusion of training exercises, and inflatable tanks and trucks lined country roads.

This phoney army must have worked, as the Germans believed that the Calais area was going to be where the landings would take place and even on D-Day they thought the Normandy assault was a distraction.

Bad weather led to the postponement of the invasion initially, and when it finally got under way it was in less than ideal conditions.

As the troops tumbled out of the landing crafts and flung themselves on to the beaches, in most cases under heavy fire, back on the farms of Courier Country workers tumbled out of bothies, cottar houses and lorries to start the work of the day.

At that time of year this included turnip and sugar beet thinning, where no doubt the talk among the squads would centre on the progress and the privations of the war.

Among these squads would be the old farm workers, loons too young for call up, reserved farmers and workers, Land Girls and of course prisoners of war.

Up until this point POWs mainly consisted of Italians captured in North Africa.

Following D-Day, German POW numbers began to rise and the dire labour shortages of 1944 meant they were also used to work on farms.

By 1943, 37,000 POWs worked on farms and the Land Army had reached its peak of 80,000 girls.

The big harvest of 1944 saw a request by the Ministry of Agriculture for a further 36,000 POWs. Germans were used, beginning with that year’s potato harvest.

Careful selection of German prisoners was required to weed out Nazi fanatics, but it was not long before the Germans began to be appreciated for the quality of their work.

Eventually they were billeted on farms after initially being held in camps such as Annsmuir near Ladybank.

Anyone thinking on June 6 that the ending of the war was close was in for a shock.

Tough German resistance in Caen and the bocage country inland of the Normandy beaches slowed up the breakout, and the subsequent setbacks at Arnhem and the Ardennes meant the war in Europe was to drag on until the following spring.

Parts of Europe freshly liberated by the advancing Allies now needed feeding. Holland especially suffered greatly as retreating Germans had flooded vast areas of the productive polder lands, creating starvation conditions for the Dutch population in the winter of 1944/45.

Indeed even after the war in Europe was won in May 1945, food shortages continued and Britain played its part in addressing the problem right up until 1954, when food rationing was finally lifted.

In many cases in contrast to the military element of D-Day which was leading to the ending of hostilities, for farming it could be argued that D-Day was just the beginning of another campaign to produce more and more food for consumers both home and abroad.