Vines grow well in certain areas and not at all well in others, and it is very much the same with raspberries.

The French describe the combination of soil, climate and aspect as ‘terroir’. Although there is no equivalent Scots word, the concept was well understood by the consortium of canny Blairgowrie businessmen who founded Blair Estates.

They had seen the emergence of raspberry growing around their home town in the late 1890s and noted the profits that could be made.

A three-ton-per-acre crop not unusual in these early days could be sold at £28 per ton to gross £84 per acre. Costs including rent and picking came to only £30 per acre, leaving a net profit of £54 per acre. This would equate to an unbelievable £5,620 today so it is little wonder that there was a “gold rush” into raspberry growing not just by existing farmers but by people from all walks of life.

By 1900 around 1,000 tons of fruit was being despatched annually by rail from Blairgowrie, mostly heading for the jam factories of the English Midlands.

The consortium behind Blair Estates was watching the situation closely. In 1902, when 450 acres of land at Drumellie and Essendy came up for sale, they were quick to pounce.

Some thought that, being four miles to the west of Blairgowrie, it was too far away from the berry heartland and that the soil might not be suitable.

In fact the businessmen knew their ‘terroir’ well and the land was ideal for raspberries, especially because most of it had a northerly aspect making the buds less susceptible to frost damage.

The consortium, represented by Blairgowrie law firm Keay & Hodge, quickly sold off some lower-lying land near Marlee Loch and then set about dividing the remaining 250 acres of prime berry land into holdings varying from five to 25 acres.

Most of the land was sold on instalment plans and the new owners came from all walks of life.

There was, however, at least one local family involved. The Nivens had been at nearby Drumellie as tenant farmers since 1885 and they did not miss the opportunity to be part of the new berry bonanza.

By 1918, following medical discharge from the army, Robert Niven became manager to a Miss Irwin at the holding known as the Sholach.

Broughty Ferry born Miss Irwin lived during the summer at the Sholach but spent much of her time in Glasgow as organiser of the Scottish Council of Women’s Trades.

All of this and much more has been recorded in a recently published book written jointly by Robert Niven’s son Jim and granddaughter Irene Geoghegan.

“My dad started writing down his memories once his health began to fail and he soon became completely absorbed in the task.

“After he died I realised that this could be a book, and started writing some chapters myself,” said Irene.

The father-and-daughter combination has worked well. Jim Niven’s lifetime in the berry industry is complemented by Irene’s experience as a crop scientist and plant breeder. All told it makes their book Berry Treasured Memories an excellent read. One of its great strengths for students of agricultural and rural history is that the memories are first hand and unlikely to be matched.

The Niven family were to become an integral part of berry growing at Essendy.

At one stage they were processors, too first with a bottling plant and then with an on-farm jam factory.

It wasn’t all profit, however. There were bad years, some of them catastrophic.

The First War World saw prices rising as demand for fruit for jam-making soared.

By 1920 raspberries were trading at £100 per tonne. But as the depression set in, prices slumped.

Jim records that in 1930 the season opened with buyers offering £34 per ton, but within a few weeks it was down to £9 per ton and then no offers at all.

Early sellers breathed a sigh of relief and late sellers in some cases saw their berry growing careers come to an end.

The book also contains a huge amount of statistical information on the all-important weather. Hard winters weren’t so bad, but a sharp frost in May could spell disaster.

However, the Essendy growers mostly survived and built up a reputation for quality fruit.

Jim Niven as a young man in the 1930s started to do contract horse work for other growers, especially those with smaller acreage.

For berry work the requirement was for a smaller, more nimble horse, and Jim’s first purchase was a West Highland garron.

A slightly larger Shire followed, then to be joined by the first tractor a Fordson E27N.

The breakthrough in mechanisation came in the late 1940s with the introduction of the narrow version of the Ferguson TE 20. This special version of the ‘wee grey Fergie’ was converted for raspberry use by Reekie in Arbroath. With a wheel track of only 32 inches it could easily work between the rows.

Much of the book, however, is devoted to that most important of elements the pickers. No pickers meant no harvest, and the Essendy growers had to make sure they could muster several hundred willing workers by the first week in July.

In latter years it was a case of sending buses to Dundee or Perth. Some even went daily down to the mining villages of Fife.

But in the early days the pickers mostly women and children came for the season. Some were travellers but the majority came from Glasgow and the west and, of course, needed accommodation.

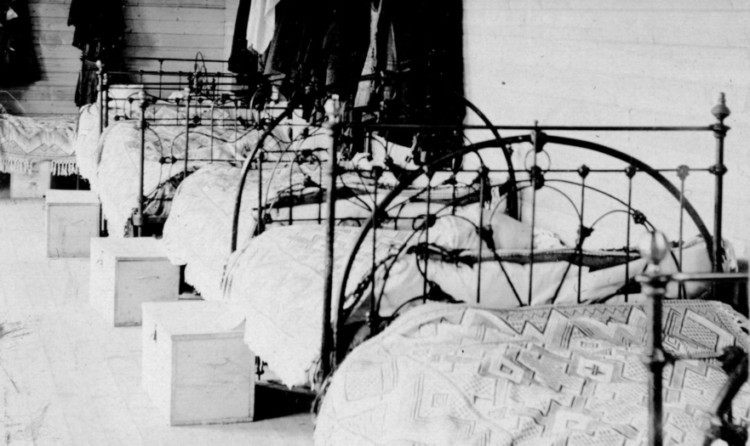

Blair Estates still had eight acres of moor unallocated and, working in cooperation with the growers, they set about building the summer camp which soon became known as Tin City. It had 18 brick-built dormitories and another six made entirely of corrugated iron.

By 1905 it could house 1,000 pickers, all of whom would arrive by train at the start of the season and leave again at the end.

Jim Niven describes in great detail the well-regimented administration and routine that made Tin City a success.

For social historians this alone would make Berry Treasured Memories a good read. Add in Irene’s chapters on varieties, pests and diseases and it is a great account of a unique period of horticultural endeavour.

Berry Treasured Memories has been published by Blairgowrie, Rattray and District Local History Trust and costs £10, with any profits going to the trust.

It is available in several retail outlets in Blairgowrie, in Waterstones in Perth and Dundee, and online at Amazon.

Irene has set up a dedicated email account at igeoghegan3@hotmail.com to provide further information.