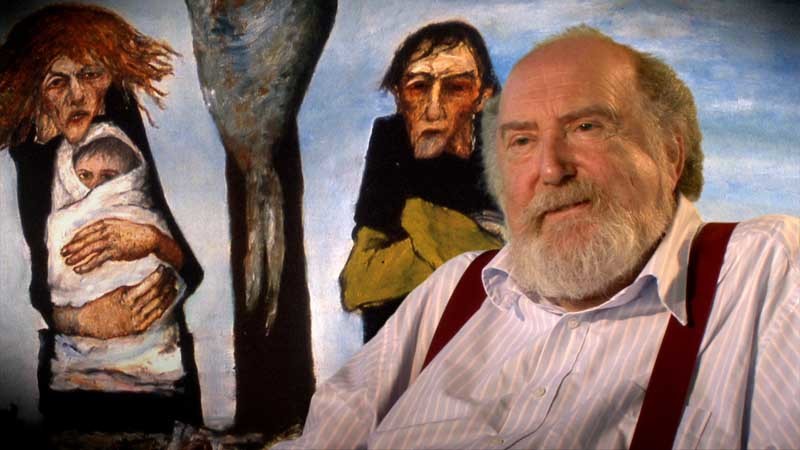

John Bellany’s work hangs in the world’s most prestigious galleries and in the homes of David Bowie and Sean Connery. One of Scotland’s greatest living artists, he has taken part in a documentary about his life created by his film-maker son Paul. He tells Jack McKeown about Fire in the Blood.

In 1988, deeply ill after a liver transplant and unsure whether he would survive, John Bellany picked up a piece of paper and sketched his masterpiece. Drawn in burnt orange, the self-portrait shows the gaunt artist’s head on the pillow of his hospital bed, the tube from a drip disappearing up one nostril and his teeth exposed in a rictus of agony.

“That’s the best drawing I’ve ever done in my life,” he says. “After the operation I developed an infection. It was looking pretty grim and I was in a bad way. About 3am one night I thought, that’s me I’ve had it. The agony was so colossal. I thought this might be the very last thing I ever do so I’m going to make it the very best I can do.

“I felt as if I was drawing with fire. It was as if the picture was drawing itself. I’m sure that was what it was like for Picasso or Matisse, but for me that was the first time it had happened. When I was finished I was completely drained of all my energy. I lay back and thought that was the end of me.”

The thread Bellany’s life was hanging by was the result of decades of heavy drinking, culminating in a cluster of years in the 1970s when the artist then one of the most acclaimed in Britain was consuming an entire bottle of rum each day. Even during his most self-destructive phase, Bellany felt compelled to work and would spend at least 10 hours a day in his studio.StudiedBorn in the fishing village of Port Seton, on the coast of the Firth of Forth, Bellany (67) studied at Edinburgh College of Art then the Royal College of Art in London. Fans of his work include David Bowie, who visited Bellany and was photographed next to a portrait of himself, Sean Connery and Damien Hirst.

“They’re all okay, these people,” he says of the more famous Bellany collectors. “You think they might be different but they don’t have any airs and graces, they’re just people. What surprised me about David (Bowie) was that he had heard of my work a long time ago. He was a student at the same time I was and knew about my painting back then. David’s a lovely guy and has been a great friend.”

The Scottish artist Peter Howson has cited Bellany as one of his earliest inspirations and said drawings done from his hospital bed are “in the class of Michelangelo”.

Bellany met his first wife and mother of his three children, Helen, when he was a student in Edinburgh. Eventually, he left her and remarried. His second wife Juliet committed suicide in 1985. Bellany later remarried Helen and the couple remain together to this day.

Much of Bellany’s early work drew inspiration from the fishing community he grew up in. His father was a fisherman, and the anchors in Bellany’s childhood came from his Calvinist upbringing and stories surrounding the Eyemouth disaster of 1881, when 46 boats set sail into a storm and only 26 returned.

During the next stage of his career many of John’s paintings were very dystopian, portraying nightmarish creatures that were half-human, half-bird.Scholarship”I got a scholarship to Spain and saw Goya at the Prado,” he explains. “Then in 1967 I was invited to East Germany where I visited Buchenwald concentration camp. It had such an impact on me. I’d had such a happy childhood and this incredible apparition came to me from Buchenwald. I’d never dreamed humans could be so evil. It was horrific.”

Coupled with his drinking, his visit to the Nazi death camp had a powerfully negative impact on the artist.

“That’s when the darkness came,” he continues. “Buchenwald brought on the darkness and it didn’t lift for a long time. It’s still with me now to a certain extent.”

During the 1980s his health began to fail him and Bellany became increasingly ill, yet continued to maintain a hectic working schedule. His portrait of cricketer Ian Botham inspired one national newspaper to dub 1985 “the year of John Bellany”. Three years later, his health had deteriorated to such a degree that he would die unless he got a liver transplant. A donor was found and he underwent the operation but developed complications, which brought him within a whisker of death.

Eventually he recovered from what was at the time the longest and one of the most complicated surgical operations in the world. Had he been born any earlier, the procedure would not have been invented when he needed it.

“I was very fortunate to be one of the first liver transplant patients of all time,” he says. “It was done in Cambridge Hospital, which was the only place in Britain that was doing liver transplants. It was a very traumatic experience. I never knew if I was going to come back alive or in a coffin.”WakingAlmost the first thing John did after waking up was start drawing.

“I had to wear a mask and I couldn’t speak. The first thing I asked was for a bit of paper. The nurse brought me some paper and I did a drawing of her. I thought to myself, if I can draw that means I’m going to get better.”

And get better he did, though the process was long and painful. His weight dropped to seven stones and pictures from this era show him emaciated and clearly in great pain. He observed, drew and painted his way through it.

“I got the professor who ran the hospital to sit for me,” he smiles. “I wouldn’t let him go because I wasn’t finished. I told him it might be the last thing I ever painted. He laughed and said he’d stay because the painting would be worth a fortune then.”

One of his most uplifting days was when Rolf Harris dropped in to see how his recovery was going.

“Since then I’ve had nearly 22 wonderful years that I didn’t expect and probably didn’t deserve and I’ve been grateful for every moment. That I’m still here has a lot to do with the hospital’s doctors, surgeons and nurses. We should be paying them double, not cutting back on them.”

When he thanks medical workers, Bellany is referring not just to his transplant, but to the treatment he received following a heart attack in 2005. Medics managed to revive him after he had lain with no pulse on a pavement in Glasgow for more than a minute.

Now, Bellany has taken part in a documentary made by his film-maker son Paul, who left his job as a visual artist on the Harry Potter series to make the film. Fire in the Blood due to be broadcast on BBC2 on Easter Monday is a courageous work that addresses Bellany’s alcoholism, liver transplant and the suicide of his second wife.

His first and current wife Helen takes part, as do his two sons, Paul and Jonathan, and his daughter Anya. Pulling no punches, the programme addresses his daughter’s teenage difficulties as well as Paul and Jonathan’s spiral into the far-right music scene. Bellany is proud of his son for producing such an unflinching account of their family history.Special”He really rose to the occasion and pulled off something very special,” he says. “It’s a very difficult subject, and there really were no holds barred. He said, ‘Dad, if we start it like this we’ll have to carry on.’ I said that’s the only way you can produce something worthwhile, by following your vision and being courageous.”

More than 100 hours of footage were boiled down for the hour-long feature. In it, Bellany’s sons remember their childhood and how their bedroom wall was covered with the frightening, nightmarish creatures their father had painted.

It could not have been easy for them to get to sleep at night. John laughs heartily at this suggestion. “No, maybe not. But it brought them up to know that everything isn’t rosy and nice about the world. When they were children we went to other houses and they would ask why there weren’t paintings on the walls. One day the home owner said I don’t have paintings but I have flying ducks. So we weren’t that bad really.”

A down-to-earth and relatively private man, Bellany says he is happy with the portrayal of his life his son has produced.

“Even though all these things have happened I’ve had a wonderful life. We’ve had our ups and downs just like other folk. I’ve got eight grandchildren now. I’ve been so lucky.”InterestNow approaching his 68th birthday, interest in Bellany’s career remains high. Awarded the CBE in 1994, his work is on display at the Museum of Modern Art, the Metropolitan Museum in New York, the Scottish National Galleries and the Tate. A portrait of his friend Michael Spens, a senior research fellow at Dundee University, hangs in the university’s law library.

This month the Beaux Arts Gallery in London is staging an exhibition spanning five decades of his work.

Not everything is rosy however. A few weeks ago John was diagnosed with macular degeneration, a loss of central vision that can make it difficult to read, recognise faces and paint.

“It’s not great,” he admits. “And I’m worried about it. But I’ve just done a drawing this morning. My sight will degenerate further but they don’t know when. I might get worse in six months or it might stay like this until I’m 85.”

“I can hardly see the paper when I’m drawing and painting, but I just have to try and be like Monet (who suffered from cataracts). He just ploughed on and his style of work changed. He followed his passion all the way to the end.”

He pauses before adding, “And I can still see my beautiful wife Helen. That’s a blessing to me.”Fire in the Blood is on BBC2 Scotland on Easter Monday (April 5) from 9-10pm and will be available on iPlayer.