Ninian Stuart has spent his life trying to answer one key question: “Why me?”

In 1991 Ninian somewhat reluctantly inherited all 1900 hectares of Fife’s Falkland Estate – including an ancient royal palace, forest and farmland – following the death of his father in 1991.

But the hereditary keeper spent years wrestling with guilt over his birth right to the estate long before it was passed down to him.

“I’ve struggled forever, since I was a young lad, with thinking: ‘Why me?'” explains Ninian, 67. “Because I was the youngest. I have three sisters. So why me?”

Legally, the answer is simple: royal lineage.

Ninian can trace a direct family line back all the way to Robert the Bruce, whose daughter married into the Stuart family.

Born on the estate, he spent his first seven years at Falkland, “jumping bareback on ponies and ‘stealing’ apples from my dad’s orchard” before he was “sadly” sent off to English boarding school Ampleforth College.

But instead of returning to his idyllic childhood home after completing his education, Ninian left behind the path laid out for him in the “exclusive world of people who went to public school” – and he went to work.

Ninian swapped palace for homeless shelter

“When I left school, I took on a few jobs of selling ice creams at Edinburgh Zoo and working in a café,” he recalls. “And then I spent a number of years living and working with homeless people in Glasgow with charity Simon Community.

“That was, in some ways, a response to the life I didn’t want to have – a life of privilege and being treated as special.

“I could’ve lived off this place, but I didn’t want to. Glasgow was where the foundations for my life were built.”

It was in Glasgow that Ninian met his late first wife, Anne O’Donnell – a working class Glaswegian woman descended from Irish labourers.

Together, they returned to the estate when their children were six and seven years old, allowing Ninian’s own daughter Christina and son Francis to pick up where he left off.

Things would be different for Ninian’s kids

But knowing how heavily the burden of the estate had weighed on him, he decided to change things for his own children.

They attended the local primary and then Bell Baxter High School, instead of being shipped off to boarding school.

Like Ninian, they grew up playing in the same scenic countryside that Mary, Queen of Scots, used to play in, and which attracts tens of thousands of visitors each year.

But unlike Ninian, his children will not be the sole inheritors of Falkland Estate.

“My children have two very different lines,” explains Ninian. “And Anne and I came back here thinking: OK, we may have some ambivalence about being in this position and we may be struggling with it.

“But we’ll take it on, grasp the nettle, and let’s see what we can make of it.”

Leadership was sharp learning curve

Since then, Ninian has spent 33 years learning what it takes to be the ‘keeper’ of a place like Falkland, which boasts organic farmland, apple orchards, 1,000 acres of forest, numerous tenancies and small-holdings, and the renowned Pillars of Hercules cafe.

And what he found was that being a keeper of the land also meant being a leader for those who belong there.

“I am a really slow learner,” he admits. “There’s a lot of baggage that comes with inheriting an estate, and landowners do not always get it right.

“For me personally, a lot of my early working life was about everybody being equal and a sense of working towards fairness and egalitarianism.

“One of the things I’ve learned through the role that I hold here is that hierarchy is not everything, but that sometimes I’ve been ‘too saft’.

“I’ve over-emphasised ‘lets do everything together’ over that really clear sense of direction and leadership. I think I am now getting much better at that.

“So it’s taken me a long time to find my feet, and to know and trust my heart.

“And I can easily slip back into that imposter syndrome thing again of: why me?”

‘How can one person own the land?’

But on the warm, overcast midsummer day that he shows me around the estate, checking on the apples, enquiring with carpenters working on sheds, and liaising with staff, Ninian seems every bit the capable landowner – or, as he puts it, “land-holder”.

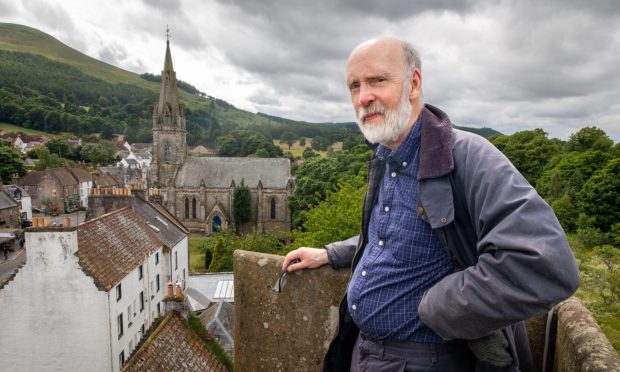

“How can one person own the land?” he asks, gazing out across the orchard, village and crowning jewel of East Lomond from his perch at the top of the palace turrets.

We climbed up here together, Ninian with all the deftness of childhood muscle memory; me trailing behind, panting.

“I deeply believe that hill or that forest can’t belong to me,” he shares. “Legally, I or the estate trust which my father set up holds title to it.

“But in reality, it holds and hosts us, the people. We kid ourselves on if we think we can own it. It’s a made-y up thing.”

What is recipe for ‘successful succession’?

This long-held egalitarian outlook is just one of the driving factors behind Ninian’s decision to “move on” the inheritance of Falkland Estate.

As he approaches an age where he’d “like to pass on some of this”, he wants to see the estate to move beyond his family line, so he can “share the resource” the estate holds.

However, he admits the exact way forward is “not yet clear”.

“It’s a bit of a journey from me to we,” says Ninian. “My children and I are wanting to move this on, but we’re not saying that anything goes.

“We want it to move on with some things that we think are really important and essential to the place.”

Falkland community under consideration

One option he and his children are exploring is having the Falkland Stewardship Trust, a charity set up in the grounds in 1994, take the estate on.

Ninian was a founding member of the charity, originally called the Heritage Trust, but is no longer a trustee.

If this were to happen, he says, a local community buyout or partial community ownership could be part of the conversation.

“If the Stewardship Trust were in a position to take it on, they’re also in conversation with the community,” he explains.

“They’ve got some money from Scottish Land Fund, and that would be looking at a community ownership model. We’re open to that, and that is one option.

“My family have been involved here since 1887,” he muses. “But if I think of the village of Falkland, there are a number of families there who have been there twice or three times as long. What if we can somehow tap into that?

“We believe Falkland Estate will be stronger with more than one family behind it.”

Falkland ‘has not got lots of wealth’

But Ninian also wants to ensure that Falkland Estate is financially solid for generations to come, meaning any community ownership agreement would be subject to “a lot of capital behind it”.

“When my great-grandfather took this on, he was very, very wealthy,” he explains.

“But now we have the money from what we grow, and from rents.

“Falkland has not got lots of intergenerational wealth. That’s the reality.

“So if the community were to take on all of it, it would be really important that they would draw in a lot of financial backing and capital behind it, in order to make it viable.”

Go Falkland is part of sustainable legacy

It’s important to Ninian that his family’s legacy at Falkland Estate is one of sustainability.

That’s why this summer, the estate will host its second ever Go Falkland regenerative agriculture festival.

Hugely expanded from its inaugural 2023 event, this year’s festival will host more than 40 food industry sessions – from farmer workshops and grower talks to information sessions from policymakers – over the course of two days.

For Ninian, it’s an event which encompasses what Falkland is all about – growing, regeneration and, of course, hospitality.

“When the royal family used this place, it would’ve been for entertainment and hosting,” he observes.

“And one of the advantages of a place which has been passed down the line is that it has been protected from the worst ravages of exploitation.

“So there is both a privilege and a burden of responsibility within these places to try and keep them well.”

Go Falkland 2024 takes place at Falkland Estate on July 17 and 18 2024.

Conversation