Realising he’d been helicoptered to an oil rig to replace one of the 45 workers killed in the 1986 Shetland Chinook crash was a defining moment for Jake Molloy.

The formidable trade unionist, who will be made a Master of the University of Aberdeen today, says it inspired him to speak out for offshore workers contending with “wild west” conditions in the North Sea.

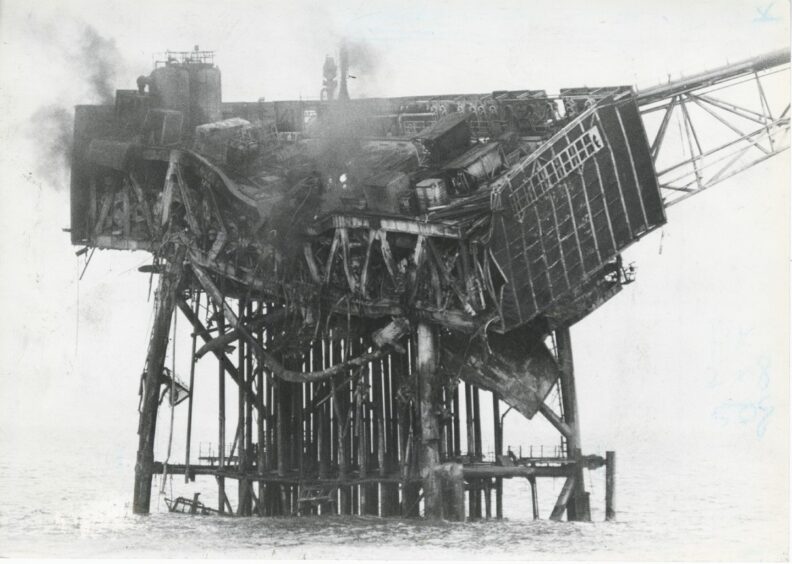

Losing friends among the 167 men killed when the Piper Alpha platform exploded just two years later only sharpened his focus.

That tragedy forced a watershed for the oil and gas industry and a shift from minimal oversight to safety first.

Jake helped lead the charge in calling for change, gathering offshore worker reports about repairs and maintenance, gas leaks and temporary patches on pipes.

Doggedly gathering evidence, he waved red flags on behalf of workers too afraid to speak up about safety on North Sea rigs for fear of losing their jobs.

“It’s been sheer luck down the years, rather than good management or good control, that’s prevented another major event in the North Sea,” Jake says.

“There was an oppressive culture on board the rigs through the eighties and up to Piper Alpha. To challenge that would see you sacked.”

Piper Alpha took terrible toll

Piper Alpha sparked the biggest fundamental change, says Jake, and most importantly it got the offshore oil and gas industry properly regulated.

“Piper had a terrible toll, but things changed in a way which could never have been achieved had we not had an accident of such devastation.

“We all knew we were in a dangerous industry, but nobody thought you could destroy an entire platform and kill that many people.”

When he retired in 2023, Jake had worked his way up to the role of RMT Regional Organiser, with responsibility for all offshore energy activity.

This included engaging and organising divers, seafarers, catering, engineering, drilling and renewable sector workers.

Born and raised in Dundee, Jake left school aged 16, before sitting his O-Grades, and was a plumber by trade.

He was “fitting a bathroom suite for a guy that was working for Chevron,” when he learned about the huge demand for trades offshore. Then in 1980 he joined 300 others working at the Ninian Central oil platform.

Losing many of the workmates and friends he made working in this dangerous offshore environment spurred Jake to push for change.

One of the hardest to take was the Chinook crash in 1986.

“It was a sore one, because I had been made redundant in July that year along with thousands,” recalled Jake. “Oil price collapse always means redundancy.

“I got a call asking me to go back offshore, but I didn’t know where I was going.

“It was only when I got there I realised I would be filling the boots of someone who had been killed in the helicopter.”

Giving people a voice

It hit home when he was given the locker of one of those 45 victims. A man he had worked alongside and considered a friend.

He said: “I got involved in the campaign to get rid of the Chinooks because I felt that bad being out there. And we got rid of the Chinooks.

“Then a couple of years after that we had Piper and lost friends on there. Again, I went down a route of campaigning on health and safety.”

Elected safety rep in 1990, Jake used his position to agitate from within.

“We started raising issues,” he says. “People were coming to me and saying Jake you raised this issue, can you raise this as well?

“When the safety rep legislation came in 1989 that put me in a role which I had never been in before.

“But I took to it and I really enjoyed it. And we made a real difference. We got a good bunch of safety reps together, we got on the safety committee and we were making things happen.

“That gave me the feeling that maybe I could influence change.”

Then in 1997, Jake was elected general secretary of the offshore industry liaison OILC which later merged with the RMT Union.

“I was approached to stand and won it, which surprised me,” he says. “If that hadn’t occurred, I might have gone down a different route.

“I was actually thinking about giving up offshore work. But I got that involved in the strikes and disputes and everything else, the rest they say, is history.

“The whole idea of giving people a voice only came about as a consequence of Piper Alpha.”

Critical to drive change

From there Jake started organising conferences and campaigns and pushed through changes in working times and training.

“You listen to the workers,” he said. “That’s the key for me. I’m the one that makes their voices heard because they don’t feel able for lots of different reasons.

“Just that inherent fear and the nature of the industry.

“You are bringing about change as a consequence of their input. The input of the guys at the coalface.”

But you need to be critical to drive that change, he says.

“Every change that we have managed to bring about has had a consequence.

“Before Piper it was like the wild west out there. Much as it is in the renewables side just now.”

Deepwater Horizon aftermath

Jake was flown over to the US to speak with offshore workers in the aftermath of 2010’s Deepwater Horizon explosion.

Eleven people were killed in the disaster at the BP drilling rig.

And five million barrels of crude oil were released into the Gulf of Mexico, killing an estimated one million seabirds.

“In the role you start to get a feel for what is happening internationally,” says Jake.

“Deepwater Horizon was a big event as well and I was asked to go by the US Chemical Safety Board and talk about what we were doing for workers in the North Sea.

“To try and involve them more and give them greater powers and greater influence to try and prevent accidents.

“In other words, give them [offshore workers] the ability to speak out and say no, because that was what was missing with Deepwater Horizon.”

Today, Jake says horror stories coming from the offshore wind sector should be cause for alarm.

“My fear for the renewables side is we are doing the same thing over again,” he adds.

“Workers are going out there, precarious work, short-term contracts, agencies, working on vessels which they have not got any real knowledge of.

“The regulator isn’t there to the extent we think they should be. If you look at the statistics, they tell us it’s a pretty hazardous environment with the number of accidents that are occurring.”

‘It’s an incredible honour’

While he doesn’t usually have much truck with academia, Jake says his work with the University of Aberdeen and its Just Transition Lab team triggered a rethink.

Since 2022 Jake has served as commissioner on the Scottish government’s Just Transition Commission, providing advice and scrutiny on how best to deliver the shift to a low carbon economy. Particularly for workers and society.

And it was sharing his stories with that team, and the stories of other offshore workers, that led to the university’s decision to shoulder-tap Jake for an honorary degree.

“Now that it’s happening, I’ve got to say that it’s an incredible honour,” admits Jake. “To be recognised by a seat of learning such as the University of Aberdeen is special.

“But the recognition for me should be for the people I have represented.

“It’s not me that’s brought about the change. It’s the workers.

“Through sacrifice and through commitment.”

Conversation