Ahead of a public lecture, Dundee University geologist Professor Rob Duck tells Michael Alexander why rising sea levels in the Tay estuary might eventually force some areas of developed land to be returned to nature.

It is Scotland’s longest river which has helped shape life and landscape in the area for thousands of years.

But with scientific data predicting a climate change-fuelled 25 cm rise in sea levels in the Tay estuary by the end of this century, what might the future hold for the 120-mile long River Tay and the communities that line it?

The question will be floated in a public lecture by Professor Rob Duck, Emeritus Professor of Environmental Geoscience at Dundee University on Wednesday January 8 when he looks at the impact of human intervention over the last 200 years and how climate change since the industrial revolution might affect future sea levels.

Organised by the Abertay Historical Society as part of the Dundee Afternoon Lectures Programme, the talk has been arranged as part of Scotland’s Year of Coast & Waters 2020 and is increasingly topical given the latest Met Office figures confirming that a series of new records for high temperature were broken in the UK in 2019, concluding a record-breaking decade.

“I’ve called the talk ‘Two Centuries of Appreciation and Modification and What Might the Future Hold?’” explained Professor Duck, who graduated in geology from Dundee University in 1977 and who has spent almost his entire working life specialising in coastal and estuarine studies.

“There’s been an amazing amount of work done to modify the Tay over the last couple of centuries, but I also want to try and suggest what the future might hold as we adapt to climate change.”

Professor Duck’s lecture will look back to some of the early scientific work that changed the flow of the Tay including what Robert Stevenson and sons did to dredge the channel to Perth in the 19th century.

The engineers’ work between 1834 and 1842 made a “massive change” because it altered the speed that the tide enters the Tay estuary and meant that ships could get to Perth around 50 minutes quicker than they could before.

“Prior to that it was tiny boats taking quite a long time to get there,” he said. “This enabled bigger ships to get there far more quickly. They kind of turned the Tay into the ‘maritime HS2’ of its day. It was a real marine motorway. This impacted on the economy of Perth and all the little ports in between like Port Allen, Newburgh and of course Dundee.”

Another crucial development that happened from the late 18th century was the planting of what are now the largest continuous reed beds in Britain and, in the early 19th century, a lot of embankment work in the upper part of the estuary.

But while the Tay’s massive fresh water flow still ensures it’s one of the cleanest major estuaries in Europe, Professor Duck said the river is not immune from the impacts of climate change.

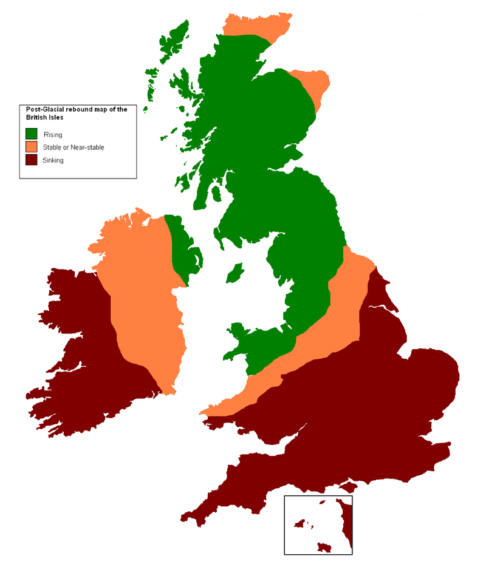

While changes in relative sea level around Scotland’s coastline over the past 20,000 years have been driven by post-glacial ice sheet melt and isostatic recovery – the land rebounding upwards after no longer being depressed into the Earth’s mantle by ice – Professor Duck firmly believes that man-made climate change linked to the start of the industrial revolution in the 1840s, is “accelerating” sea level rise in the Tay estuary.

“We know that since 1900, sea levels in the Tay – depending on location – have gone up somewhere between 3cm and 6cm,” said Professor Duck who is also chairman of the Tay Estuary Forum.

“That doesn’t sound much, but it is quite significant. The predictions are if we look to 2100 that there will be some sort of rise – 24/25cm – over the next century.

“In other words, sea level rises are definitely accelerating in this area. There’s still isostatic recovery happening here but those figures take that into account. If carbon reduction targets are not met it could be worse.”

Professor Duck said new sea defences such as the “very well thought out” ones along Dundee’s Waterfront are well designed to take into account sea level rises “well into the future”.

However, what’s far more difficult to predict is storminess and the potential for big storm events.

“If you’ve got a big big discharge coming down the river and you’ve got a high tide at the Dundee end, then you’ve got a big storm, that’s when you’ve got over-topping of defences and that’s when flooding will occur,” he said.

“I think there’s no doubt that storminess is increasing in the area – not just in the Tay. Although we’ve got good defences in place it doesn’t mean there won’t be flooding in the future.”

Professor Duck said melting ice caps/glaciers and ‘thermal expansion’ of water as it heats up amid global temperature increases were responsible for rising sea levels.

He agreed with the majority of world scientists this was “all due to global temperatures rising since the industrial revolution” and the start of the massive use of fossil fuels like coal.

With climate change already happening and unlikely to be stopped, he said the world had to “adapt”.

From a UK perspective, this might include giving up some fast eroding coastal areas to the sea or, in the case of the Tay, giving up some former flood-plains back to nature.

“One of the things that might be possible to do – and this is being considered in the Forth – is to remove some of the embankments in the upper part of the river that were put in to create farmland in the 18th and 19th century,” the professor said.

“This would allow the water to go back to where it used to go onto natural floodplains. Call that ‘managed realignment’, but it’s something that might, shall we say, have to be considered in the future.”

• Professor Rob Duck: What might the future hold for the Tay?, D’Arcy Thompson, Dundee University, Wednesday January 8, 2.15pm. Cost £2, pay at door.