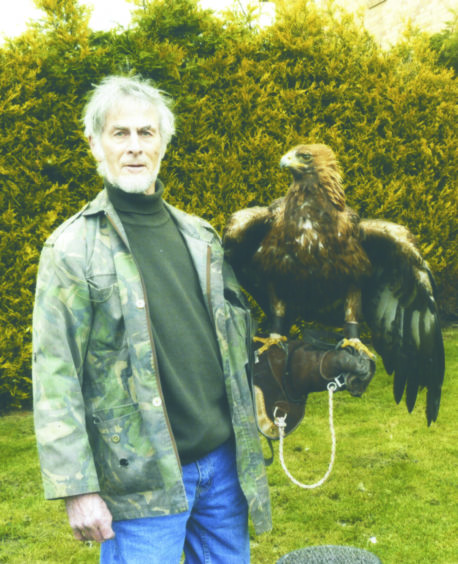

He’s Scotland’s foremost living nature write and has just penned his 40th book. Jack McKeown talks about woods, wolves and wildcats with former Courier columnist Jim Crumley.

Many journalists become authors but only one wrote their first book on a typewriter in a tent on St Kilda.

Having been a journalist since he was 16, in 1988 aged 40 Jim Crumley left his features job at the Edinburgh Evening News, having been commissioned to write a book by the landscape photographer Colin Baxter.

He spent two weeks on Hirta, the largest of the uninhabited islands that make up the St Kilda archipelago, exploring its remarkable landscape then huddling over a typewriter in his tent to write about the experience. “Fortunately some National Trust workers were out there and I got my evening meals with them,” he remembers. “I still had to carry my tent, two weeks of breakfasts and lunches, and my typewriter though.”

Writing a book in a tent on one of the UK’s most wild and windswept points sounds like an uncomfortable experience. “Looking back I was very lucky indeed,” Jim continues. “The weather was beautiful and it only rained once in two weeks. I remember walking to the high point of the island, around 1,100 or 1,200 feet and not being able to see land in any direction, apart from on one clear day when I could just make out the beaches of Harris, 40 miles away.

“My income had halved overnight but I wouldn’t have swapped the path I’ve taken for anything.”

That first book, St Kilda, was released in the autumn of 1988. This month saw the publication of The Nature of Summer, Jim’s 40th book and the conclusion of his quartet looking at Scotland’s seasons.

Jim was born and brought up in Lochee, and his grandfather was on Dundee FC’s 1910 Scottish Cup winning squad. He left school at 16 and joined The Courier as a trainee reporter, spending five years on DC Thomson publications before moving to the Daily Express then becoming the youngest editor in The Stirling Observer’s 150-year history. He wrote a weekly column for The Courier from 1997 until 2018.

Jim’s book writing career was given a boost when he interviewed the late Mike Tomkies for a newspaper feature. A colourful figure, Tomkies was the showbiz correspondent for the Daily Express during the 1960s. He lived in Hollywood, interviewing everyone from Robert Redford and Cary Grant to John Wayne and Steve McQueen, before turning his back on show business to spend the last 50 years of his life living in and writing about wilderness.

“I hit it off with Mike and he introduced me to his publisher, Jonathan Cape in London, who made encouraging noises and eventually commissioned me to write A High and Lonely Place, about the Cairngorms,” Jim continues.

For many years Jim lived in Balquhidder, in Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park, first in a cottage and then in a studio apartment above the Kings House Hotel. He now lives a slightly more domesticated existence in Stirling, though remains within easy reach of his favourite wilderness.

For the last couple of months, like the rest of us, Jim has had to make do with walks that are closer to home than the remote and wild places he’s made his living writing about.

“I’ve been walking every day but I can’t get to the places that really feed my soul,” he says. “Spring up at Glen Finglas in the oak woods is very special and I am sorry to be missing that this year.”

Jim is hopeful restrictions will be lifted by his favourite time of year – and the one that kicked off his quartet of books on our seasons. “Autumn has always been my favourite season. I love the influx from the far north and the changes that happen to the land and the trees.”

Though the experience of a lifetime of summers is poured into his latest book, Jim spent one particular summer immersing himself in research.

“I went to the Lofoten Islands in Norway during the time of the midnight sun. Those islands are extraordinary. It’s like being surrounded by 50 of Skye’s Cuillins, with sea eagles everywhere.

“I went to a crag near Balquhidder where I’ve been watching golden eagles for more than 40 years. I was at Glen Orchy, Glen Dochart, the Bass Rock. I explored the coast of Berwickshire and spent a week in a place called Burnmouth.

“I like to think I know Scotland well but I’d never heard of this tiny village, Burnmouth. There’s a headland above it and I went up there on the summer solstice and watched seals play and a pod of dolphin swim by. That evening I was sitting in the living room of my rented cottage and the same pod of dolphin swum back past. I thought to myself, I’m sitting on my sofa watching dolphin swimming in the sea – and getting paid to do it.”

Few people know Scotland’s wild places better than Jim. If he had to pick one, what would be his favourite Scottish spot?

“If you pinned me down and made me choose I’d say the west coast of Mull. It’s got everything from mountains to beaches and a surprising amount of woodland. I go back there whenever I get the chance.

“I grew up in Dundee and one place I think is fabulous is Tentsmuir. It’s so rare to have the forest running right into the sand dunes, there are the common and grey seal colonies, and of course you have sea eagles there now. I was invited to read poetry at StAnza for the first time this year and I wrote a poem called Tentsmuir 2050, about the forest and how climate change might reshape it.”

Scotland’s landscape has undoubtedly undergone change in all the long decades Jim has been wandering its paths. Does he think it has changed for better or for worse?

“If you’d asked me 10 or 15 years ago I’d have said it was struggling. There was all the grouse moor and climate change was having an impact on our coasts. Over the past decade or so there’s been a shift which gives me grounds for optimism.

“A lot of new native woodland has been planted. We’re seeing community woodland, community buyouts and that kind of thing.” Perhaps surprisingly, Jim also has praise for Danish billionaire Anders Povlsen, who is Scotland’s biggest landowner with 221,000 acres. Instead of using his land for traditional pursuits such as shooting, he has begun an enormous and ambitious programme of rewilding, planting millions of trees.

“Povlsen does seem to be very well motivated,” Jim says. “He’s doing some very good work bringing the land back to how it once would have looked. My only concern is all that land being in one man’s hands. I do think a lot of the other landowners could learn from his example though.”

Another area Jim has a great and longstanding passion for is the reintroduction of Scotland’s one-native species.

“The sea eagle and beaver reintroductions have been hugely successful. Since the lockdown began I’ve been cycling out to the River Forth and there are beaver down there, just 400 yards from the M9 and half a mile from Stirling Castle.

“Already they are having a benevolent impact, mitigating flooding and restoring the landscape to how it once was. Farmers are complaining but the key thing is to give them time. Beavers are here for the first time in 400 years. It might take 30 years before they’ve imposed a new ecosystem and we can properly assess the benefits of having them back.”

There is one animal whose return to Scotland Jim has spent decades pushing for. “There now isn’t a single country in mainland Europe where wolves haven’t returned,” he says. “They’ve had such a benevolent effect on other species and on landscapes.

“Deer and other herbivores get moved on by them so they don’t overgraze areas. They help manage animal populations. We have the perfect habitat and climate for them.”

What about fears wolves will prey on livestock or even attack people? “Norway has managed its wolf population and only allows four packs for the whole country, which is roughly comparable to Scotland in terms of population and landscape. That’s four packs of 40-50 animals. In the Highlands of Scotland you would almost never see them. We have a very good human-to-landmass ratio and there would be plenty of room for us and for wolves.”

In fact, there is only one native species Jim doesn’t think it’s a good idea to bring back. “The problem with lynx is I think they would spell the death knell for wildcats, and I would rather see the wildcat recover than have lynx back. There are only two populations of wildcats left and the two conservation groups that help them don’t work with each other – in fact they throw insults at one another.”

Jim is just as passionate about restoring Scotland’s landscape as he is about reintroducing lost species.

“We have too many grouse moors. I think there’s a very good argument for increasing tree cover, particularly on the islands. If you look at islands that are in lochs they’re covered with trees. That’s what natural island vegetation looks like, not the barren landscape many of our islands have.”

With more focus than ever on Scotland’s wild places should fans of Jim be looking forward to his 50th book before he packs up his typewriter and tent for the final time?

“I don’t have 50 books as any kind of target, although I take a bit of comfort in the whole body of my work. I don’t know anyone else in Scottish nature writing that has worked full time for so long or published as much work.

“I’m working on a book about the Lake District now, though coronavirus is likely to change the shape of that quite a bit. And I have two or three ideas for other books.

“I’m 72 but I’m in better shape than a lot of people in their 40s and I plan to keep going as long as possible. The key is to keep your thoughts on today and tomorrow rather than yesterday and the day before.”

The Nature of Summer is on sale now, published by Saraband and priced £12.99 in hardback and £6,99 in ebook.