Michael Alexander learns how the Eden Estuary Local Nature Reserve in Fife is at the forefront of conservation efforts to tackle climate change.

It was King James VI who called the ancient Pictish Kingdom of Fife “a beggar’s mantle fringed with gold”.

The frayed cloak was represented by the ragged coastline of the begging hand Fife holds out into the sea, and the gold lining was made up of the fishing villages of the coastal kingdom.

But while the beauty of the Fife coast remains all these centuries later, perhaps one of the finest jewels in the natural heritage of the kingdom today can be found at the Eden estuary, nestled between St Andrews and Tentsmuir Forest.

The estuary was designated a Local Nature Reserve (LNR) in 1978 and is noted for its key habitats and wildlife ranging from migratory birds and harbour seals, along with its sandbars, saltmarshes, mudflats, reed beds and riparian features.

Well known as a stunning backdrop to St Andrews and its famous golf courses, it’s also a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) for notable species such as Black tailed Godwit, Redshank, Grey Plover, Scaup and Shelduck.

For most people it’s a wonderful place to visit for recreation.

But for the Fife Coast and Countryside Trust team who manage it with a dedicated advisory group made up of local landowners and organisations such as St Andrews Links Trust, Scottish Wildlife trust, BASC, local councillors, SNH and St Andrews University, it’s a labour of love.

Ranald Strachan, Countryside Ranger with the Fife Coast and Countryside Trust, says the Eden Estuary LNR is a great example of a nature reserve that has people and nature at its heart with the management ensuring very strong communication and knowledge transfer between land managers and owners.

“The reserve was set up more than 40 years ago with a simple and single aim – ‘for the protection of wildlife, habitats and landscape within a framework that also emphasises the importance of education and enjoyment’,” explains Ranald.

“The site is protected by a suite of byelaws that are written and agreed to by all parties.

“The reserve has always been managed with a democratic and transparent openness and this has allowed it to lean into many challenges in its 40-year history.

“The ethos promotes the primacy of nature and this sits at the heart of all actions. However, it is a reserve run by people and for people with an objective to promote engagement and connection with this ideal.”

The coronavirus lockdown had a huge impact on the reserve with the Eden Centre closed early on, no education visits and restrictions on ranger cover and site surveys.

Looking at the bigger picture, however, Ranald said there are significant longer term challenges facing the site and none more so prevalent now than climate change.

The reserve has been at the forefront of research for decades, pursuing understanding of the causes and impacts, and latterly offering real solutions.

Saltmarsh regeneration programmes and Scotland’s largest sand dune restoration project are examples of scientifically supported and community led habitat restoration programmes.

Ranald says this integral work has been augmented by the Dynamic Coast programme report which has identified the next 30 years of potential local impacts and recommends efforts to address these impacts.

He said the cross-boundary management approach afforded by the LNR network works well and has made a strong bond between nature reserve, golf course, university and industry.

“This bond built over 40 years assists each to empathise with the other’s priorities by building partnership, accepting compromise and promoting mutual understanding,” adds Ranald.

“This network of land managers each play this critical role in supporting the other by their own volition, according to their expertise and ability.

“Collaboration builds into an ecosystem-wide application where mutually beneficial projects are supported and delivered with nature as the central support.

“This is vital to address wider issues such as pollution, increased rainfall inputs, salination changes and importantly bird disturbance.”

Ranald said the site is a fantastic bird resource.

However, in line with many other reserves, a notable decline of species across the board is being recorded.

Whilst a small number of species are thriving such as Little Egret, Pinkfooted geese and Osprey, many waders and wildfowl are fairing less well.

“It is important to note there are stable populations of some species such as Redshank, Black tailed Godwit and Shelduck locally,” he says.

“However, the decline in Grey Plover, Bar tailed Godwit, Dunlin and others cannot be ignored.

“The issues facing these birds are multi-faceted and international.

“However, there are local efforts to address declines where they are amplified by human interaction.

“Examples of this effort are the coming together of local land managers and reserves to put in place measures to help the public identify where birds are and how best to avoid or support them.”

Dr Clare Maynard of St Andrews University started working on the Eden project back in 1999, by transplanting a range of saltmarsh species, dug from local healthy marshes, in field trials around the estuary’s shoreline.

Restoring saltmarshes is a slow process, with the transplants taking a few years to establish as a functioning marsh, but once thriving the vegetation serves to soften wave energy and slow down tidal currents.

“The amazing saltmarshes that surround the Eden Estuary Site of Special Scientific Interest and Local Nature Reserve do two very important jobs: they provide wildlife with habitat and also protect the hinterland from coastal flooding and erosion,” she says.

“Saltmarsh habitats are a treasure trove of rich and unique wildlife and are increasingly valued for the role they play in keeping our ecosystems healthy.

“Unfortunately, shoreline degradation and climate change are placing saltmarshes under increasing threat.

“But this long-standing stakeholder partnership is trying to combat this habitat loss and strengthen the Eden’s shoreline against rising sea levels.”

Clare is now head of the Green Shores project – a collaboration between coastal landowners and community organisations that has created fringe saltmarsh habitat in key sections of degraded shoreline.

The development of’ nature-based’ solutions to reduce coastal erosion and flood-risk in flood-prone, low-lying coastal areas within Scottish estuaries is increasingly urgent.

She is full of praise for the “amazing job” carried out over the years by the conservation authorities – SNH and FCCT – as they deal with potentially conflicting interests of major employers and landowners around the estuary including St Andrews Links Trust arable farmers, and the MoD.

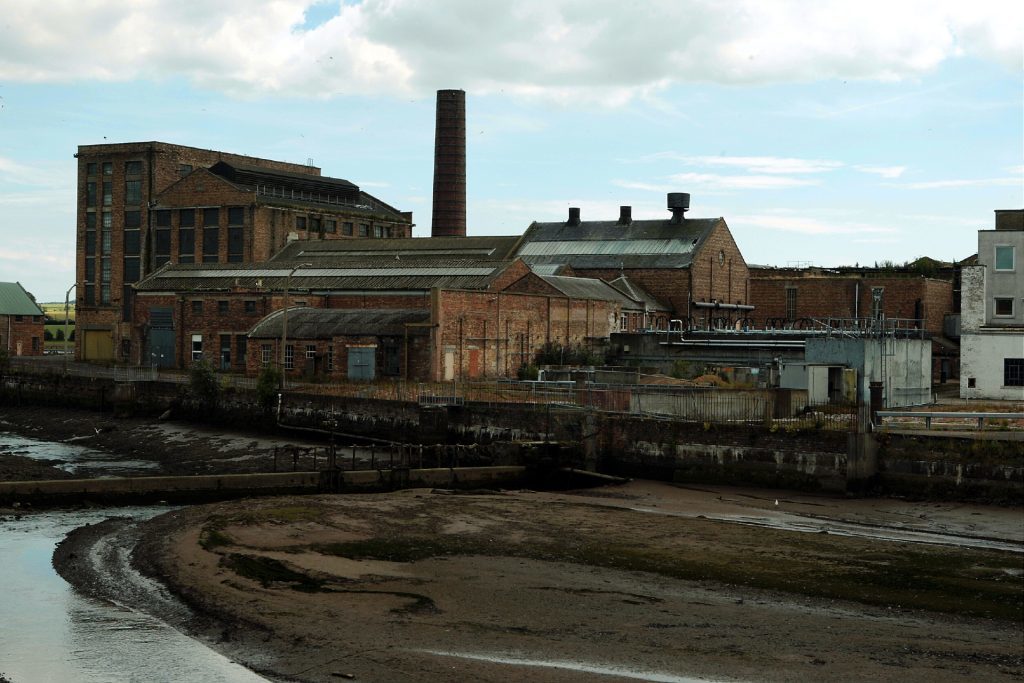

A recent addition, however, has been the St Andrews University Eden campus on the former Guardbridge papermill site, and it’s here she is taking her salt marsh planting research further with experimental planting near the shoreline at the Motray Water.

“I’ve done some successful test planting there,” she says, adding that the university with its clean energy research centre intends to be a good neighbour to the village, to the other landowners and the natural heritage that’s around the Eden campus while looking to restore and protect the land and the sea around it.

“Until those plants have grown out their roots and integrated underground, they are quite vulnerable to wave washout.

“That’s where I’ve been developing soft engineering. That just softens down the waves enough that gives the plants the chance to take hold so that they can then spread themselves.

“My initial tests worked – there’s nothing wrong with the sediments – but now I need to do something bigger and better to show the marsh actually takes into the future as well.

“These projects have taken off in the last few years – I’m the first in Scotland using them on shorelines, although I’m certainly not the first person using them around the world on shorelines.”

Clare said multi-million pound seawalls and ‘managed realignment’ – where bits of land are given up to the sea to alleviate flooding elsewhere – are two existing approaches to managing sea level rise elsewhere.

However, a third way was planting of saltmarshes which were proven to reduce the impact of erosion and flooding of the land behind it.

“I don’t ever say to landowners I’m going to solve all their flooding problems,” she says.

“I say I’m buying them time. We can’t stop sea level rising. The day is going to come you know when we all have to retreat from the coast.

“But that isn’t today and it’s not as far as we know in the next 10 years.

“We might as well try and soften our defence systems. Instead of being these expensive, hard concrete things, let’s try and get some softer systems in, and salt marshes and sand dunes are two perfect examples of that.”

Tay Bridgehead Fife councillor Tim Brett is chair of the Eden Estuary Advisory Committee which meets several times a year to support Ranald.

He describes the Eden Estuary LNR as a “wonderful resource” which he suspects many people barely know is there.

Crucial, however, is the way the partners work well together.

The Fife Coastal Path is another significant part of the area with the route going around the LNR.

Mr Brett, a Bristol University geography graduate who loves the outdoors, is also very pleased that with development of the Eden Mill project at Guardbridge, the university has “taken a lot of care with what they are doing there”.