Only one question appeared to catch Alex Salmond slightly off guard when I interviewed him in Aberdeen almost a decade ago.

Indeed, he told me at the time that no other journalist had raised the matter with him during his long round of pre-election sit-downs with members of the media, although it was not a particularly incisive query and he did not mean it as a compliment.

Sitting in an otherwise empty wing of the five-star Marcliffe Hotel in early April 2011, I asked whether Mr Salmond was confident of victory in the upcoming Holyrood vote.

What briefly flummoxed the formidable former first minister was that I was not referring to the SNP’s chances of securing a second term in office.

I was instead asking whether he was feeling upbeat about his prospects of winning his Aberdeenshire East seat.

As it turned out, a few weeks later Mr Salmond was not only elected as the constituency’s MSP, with some 64.5% of the vote, but he had also led his party to an unprecedented landslide that would realign Scottish politics and make a historic independence referendum inevitable.

The reverberations from that victory, and the political polarisation that followed, will continue to be felt later this year, if and when Scots are able to go to the polls once again, because the constitutional question overshadows everything else today.

But what would a Scottish election look like now if the independence issue was resolved, settled or, for whatever reason, did not exist?

What if Labour had won the 2011 election, as the polls had predicted would happen for several months, or if it had denied the SNP a majority, and therefore, a referendum?

Or what if Scots had voted Yes in 2014, and the nation had now moved on?

Although he could have had no idea of the scale of what would follow, Mr Salmond had of course been confident of winning both his seat and the election when we met in 2011.

Looking back at that interview now, he said he believed Labour was blowing its poll lead as a result of its mistaken belief that it “could fight an election about Westminster”.

Mr Salmond added: “The thing that will decide the election is about vision for the future. We’ve got a vision for the future of this country and they don’t.”

He was correct, and every election since has effectively been about each party’s “vision” for Scotland’s constitutional future, although in practice that has often also meant it has ended up being “about Westminster”.

This makes the democratic discourse in Scotland a bit different from elsewhere.

“I think it is very unusual for politics to be as dominated by one issue, or one identity, as is the case in Scotland with the constitution,” said Robert Johns, an Essex University professor who co-authored a book on the rise of the SNP and was the principal investigator on studies into what influenced voters at recent Scottish elections.

“There are not many examples of this, and six years since the referendum, pushing seven now… that’s a long time for this still to be as dominant as it is.”

Opinion polls

Of course, polling offers an insight into the kind of topics that might be at the top of the agenda in an election in which the independence question was not all-pervasive.

A recent example was a survey carried out by Survation last summer that asked Scots to name up to three of the “most important issues” facing the country.

Scottish independence was only the seventh highest, behind health, which was backed by more than half of the respondents, the economy, tackling poverty and inequality, Brexit, the cost of living, and education, in that order.

Prof Johns said there is “nothing unusual” about these priorities, but what made Scotland different is that “what people think about these specific issues is driven by their over-arching view on independence”.

However, he did believe that public services, and the way they were funded, would be the focus of much of the attention in a Holyrood election that did not need to consider the independence question.

“Since, even before devolution, there was this sense that the Scots were more preoccupied with public services – essentially had a more left-wing issue agenda than the concerns with the economy down south,” he said.

“I think you do see signs of that in polling. I do think Scottish elections – this is partly a consequence of which issues are devolved – but I think you would see a very public services-dominated election, in the way that a UK general election doesn’t tend to be so much.”

If the constitutional issue was somehow settled, or at least if the independence question was shelved, the big constitutional question would be about taxes.”

In the interview with Mr Salmond almost 10 years ago, despite it taking place just a month before the SNP took a key step towards an independence referendum, the first minister said at the time that the “immediate target” of a re-elected SNP government would not be independence but gaining powers for the Scottish Parliament over borrowing, corporation tax and the Crown Estate Commission.

Professor Johns also believed that the debate would have moved on to economic levers.

“Let’s say the SNP had just fallen short of the majority in 2011, so there hadn’t been a referendum, the next big discussions, I think, would have been about actually devolving more financial power, but also kind of ending this thing that ‘you can’t keep voting for good schools and hospitals when you are not responsible for raising the taxes for them’,” he said.

“That debate has largely been put on hold, I think. But if the constitutional issue was somehow settled, or at least if the independence question was shelved, the big constitutional question would be about taxes.”

Politics of the pandemic

The fact that health and the NHS has topped recent polling on political priorities in Scotland is hardly surprising in the context of the pandemic.

Perceptions of the differing way in which the Westminster and Holyrood governments have responded to the crisis would be likely to play a decisive role in this year’s Scottish Parliament election whether the constitutional question remained live or not.

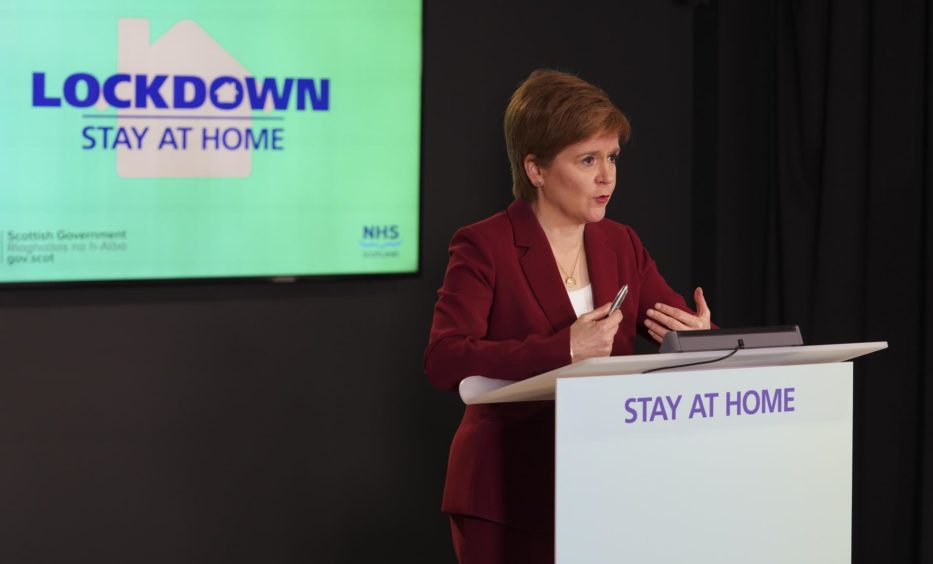

A survey in November found that 19% of the Scottish public believed Prime Minister Boris Johnson had handled it well, compared to 74% who praised the way First Minister Nicola Sturgeon had dealt with events.

Stirling University politics professor Paul Cairney suggested that perceived competency would become even more important in an election that was not dominated by the constitution.

“I guess that the focus would shift somewhat to the governing competence of the main party, which is still likely to be the SNP, in relation to its handling of Covid-19 and related services, such as the NHS and schools,” he said.

“There would still be some comparison to the UK Government, but with the recognition that this kind of rhetoric would be less useful to the Scottish Government.”

Prof Cairney added: “Maybe some people would be interested in things like further devolution to local councils, and reforming taxation, such as introducing a local income tax, but it would be difficult to see these issues catching fire right now.

“It’s also hard to see much demand for higher taxation, so the biggest debates would be about how to distribute between services.”

Climate change

Of all the priorities named by Scots in the Survation poll last summer, the environment was only the 10th highest, which would appear to buck an international trend.

The big trend that we have seen, and I think we see it consistently there so it is interesting, is that climate change made a real comeback.”

Isabell Hoffmann is the founder and co-author of eupinions, which conducts polling four times a year in every EU member state, including on policy priorities.

She said: “The big trend that we have seen, and I think we see it consistently there so it is interesting, is that climate change made a real comeback. Or environmental issues, with climate change being up front.

“Usually what you would expect to see is economic and social issues rating very strongly, and they do.

“And then you look at the European Union, and during the euro crisis and financial crisis, it was persistently up.

“But then we actually saw with the ‘Fridays for Future’ movement, the issue of climate change coming back, rising really strongly, and basically that trend was generationally independent – we saw it in different generations and age groups.”

Ms Hoffmann added: “We haven’t seen an election yet that was decided on these issues, and I think these things (elections) are very regionally specific – it strongly depends on social and political dynamics that are much more regional.

“But if there is one big trend we see and it sticks, then that is climate change.”

Opposition parties

While climate change, along with public services and tax rates, might be among the issues that would gain more traction in a Scottish election that was not dominated by the independence question, there are many others, of course.

Opposition parties would no doubt point to the education attainment gap, controversial new hate crime legislation, and waiting times for cancer and mental health services.

Perhaps there would also be more made of the evidence that has emerged so far from the ongoing parliamentary inquiry into the way harassment allegations against Mr Salmond were handled by the Scottish Government and senior figures in the SNP.

Meanwhile, the crisis that has led to Scotland recording the highest drug-death rate in Europe might feature higher up the domestic political agenda.

Drug death scandal

Austin Smith, policy and practice officer at the Scottish Drugs Forum, said the media must shoulder part of the responsibility for the way important subjects become overshadowed.

“Until recently I think, yes, there has been an issue with trying to get some focus on specifically the issue of drug-related deaths, and how services generally cope with the pandemic and so on,” he said.

“It is a crowded field. There is the Covid, and the constitutional issue, but there is also, in my personal view, there is also an issue with the capacity of the Scottish media to exercise people’s interest in a variety of topics.”

Mr Smith pointed to recent progress, such as the appointment of a minister for drugs policy in Scotland, and he hoped the issue would receive “some kind of profile within the election period.”

However, he added: “I think, tragically, what has had to happen, and this is true of Covid too, but it’s literally deaths that has pushed things up the agenda.

“It would be nice to see an earlier focus on what are a very vulnerable group of people, among other vulnerable groups in society.

“It’s about attention to the details, as it might be seen, of different policies, rather than the fact that things are neglected.

“It’s just about prioritisation and focus.”

How soon is now?

It is almost 10 years since Mr Salmond accurately predicted that voters would prioritise and focus on his party’s “vision for the future” at the pivotal 2011 election.

Varying visions of Scotland’s constitutional future have dominated the discourse since.

One day, when a future has finally been found, there may be more prioritisation and focus put on the details of the here and now.