Fossil collections in Perth and Kinross, Dundee, Angus and Fife are included in a major review of fossil collections held by Scotland’s museums. Michael Alexander reports.

Baking deserts, tropical rainforests and erupting volcanoes are not something we tend to associate with the gently undulating landscapes of Tayside and Fife.

Yet evidence of this turbulent geological past is all around us in the form of ancient volcanic plugs, sandstones and coal seams.

Over enormous timescales in geological history, the region has been covered by water and, more recently, ice, which helped shape the contemporary landscape.

But evidence of how changing geology and climate have affected the development of life itself can also be found in fossil records, including those now held in local museums.

Geological time

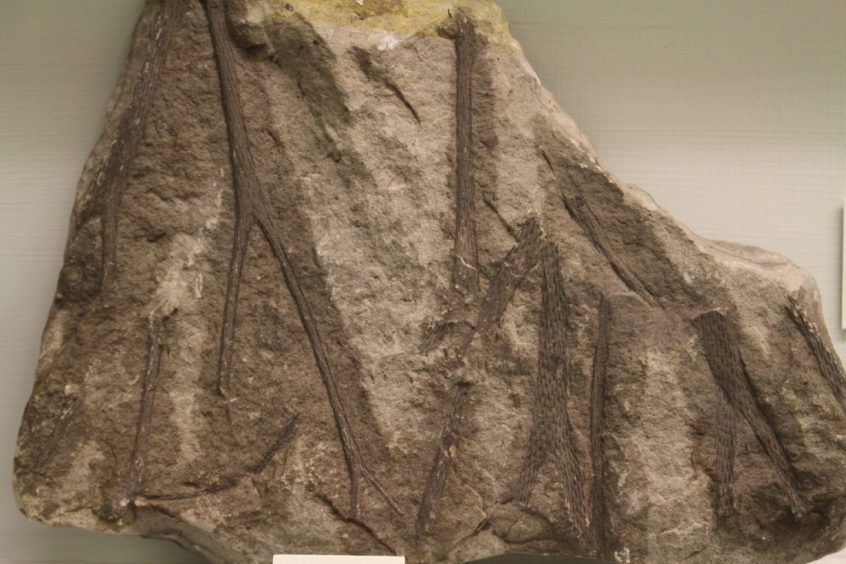

For example, between 419.2 million–393.3 million years ago, a Lower Devonian river system across what is now Angus was home to spiny sharks and shovel-headed cephalaspid fish, arthropods and primitive plants.

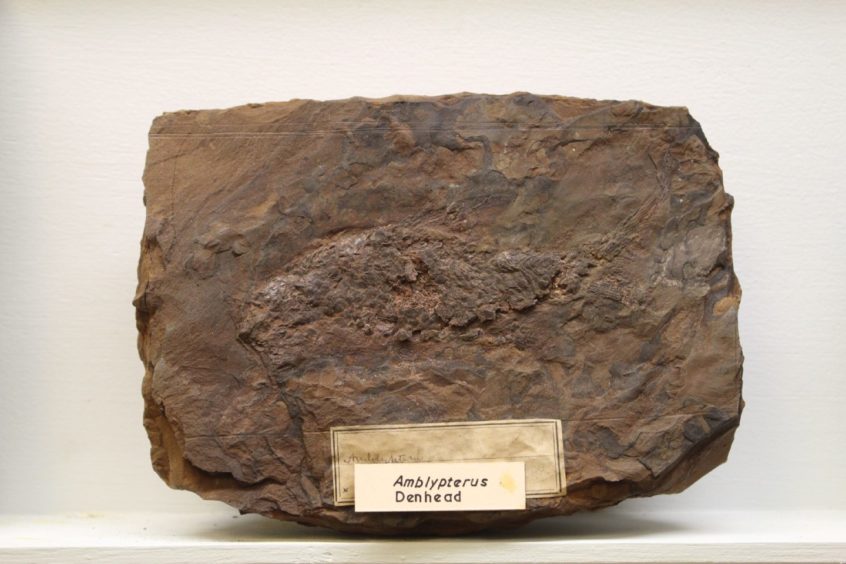

Several species of fish are known from only a single locality in this region and Perth Museum and Art Gallery holds material from Balruddery Den, Angus, rarely found elsewhere.

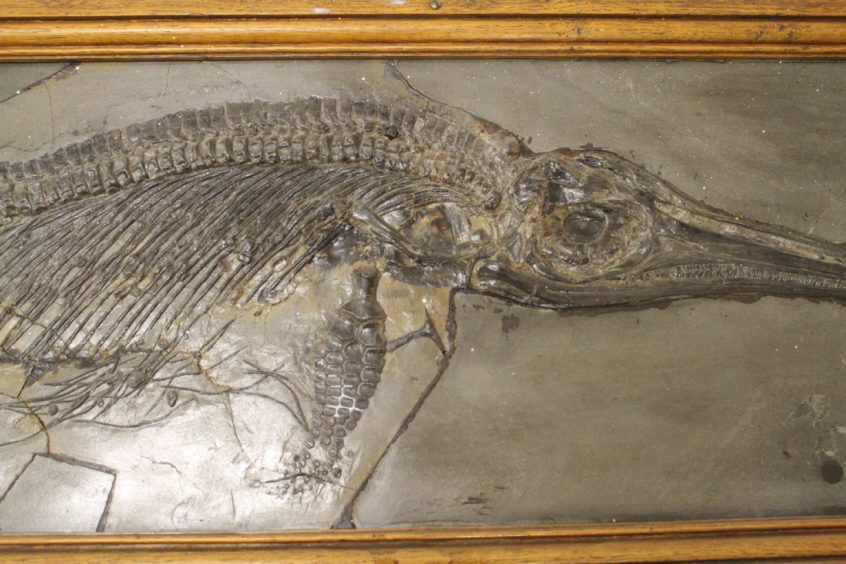

In contrast, slabs of sandstone from Dura Den in Fife bearing the large, well-preserved fish Holoptychius, with its recognisable ornamented scales, and Bothrioplepis, a heavily armoured placoderm, are found in most collections, including the Bell Pettigrew Museum in St Andrews and Fife Collections Centre in Glenrothes.

The most recent fossils, from Pleistocene Arctic clays along the Tay estuary, document warming of the climate in the last 15,000 years following glaciation and can be found in the collections of Montrose Museum, the McManus: Dundee’s Art Gallery and Museum and Perth Museum and Art Gallery.

Major review

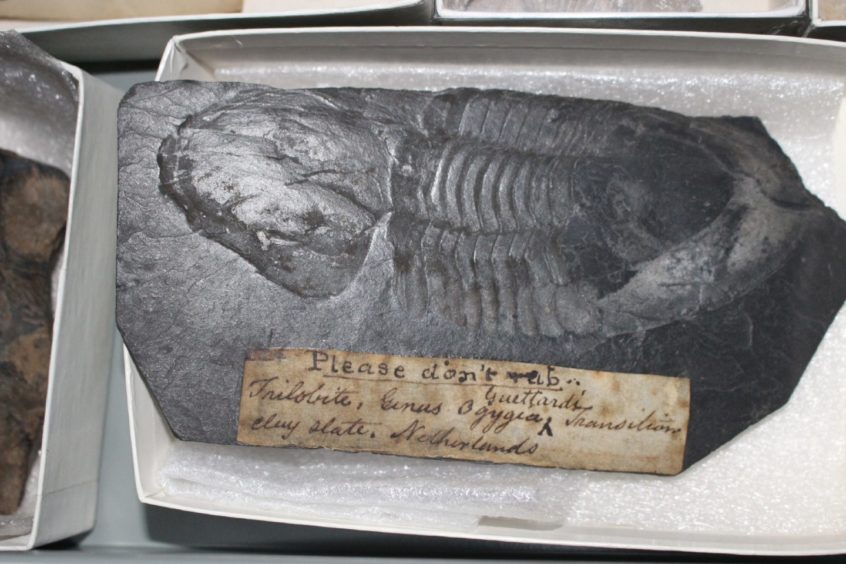

Now, the Tayside and Fife collections have been documented as part of a major review of fossil collections held in Scotland’s museums.

In total, over 250,000 specimens have been documented.

The project, funded by John Ellerman Foundation and undertaken by National Museums Scotland, began in 2019 and the resulting Review of Fossil Collections in Scotland documents specimens held in 57 museum collections across the country.

It is hoped that the review will enable greater awareness of and engagement with Scotland’s unique fossil record for both public and researchers, as well as helping the museums care for these remarkable collections in the long term.

Examples include the 410 million-year-old Rhynie Chert of Aberdeenshire which preserves the earliest known terrestrial ecosystem on Earth, specimens from which are held in Perth Museum and Art Gallery, The McManus: Dundee’s Art Gallery and Museum, Cockburn Museum and Tweeddale Museum.

Fish from the Middle Devonian of Caithness, Sutherland, Orkney, Shetland and the Moray Firth are world-famous.

Most collections across Scotland have at least a few examples with extensive collections in Nairn Museum, Elgin Museum, Inverness Museum and Art Gallery, Stromness Museum, The Discovery Centre and Glasgow Museums Resource Centre.

Fascinating

Dr Sue Beardmore, John Ellerman Project Curator, National Museums Scotland, says: “It has been really fascinating to review the hugely varied fossil collections held around Scotland.

“Some of the material featured is well known to national and local audiences, much of it less so.

“We hope that this review helps to raise the public profile of these collections, will be of use to researchers and scholars and will help museums to further develop and care for these collections now and in the future.”

Dr Nick Fraser, Keeper of Natural Sciences, National Museums Scotland says: “The Ellerman fossil review is an important and substantial piece of work.

“One striking thing is the way in which these diverse collections frequently mirror the immediately local geology and, considered together, show how important Scotland’s geological and fossil record is in understanding the development of life on Earth.

“On a more practical level, it’s also really useful.

“Expert assessments like this review set museums up to be able to start sorting and properly documenting the nation’s natural science assets.

“This benefits the museum sector generally and each of the individual museums as it gives those that need it the power to unlock these collections to make them more accessible for people, whether scientific researchers or the wider museum-visiting public.”

The John Ellerman Foundation said in a statement: “The wide geographical dispersion of populations and museums in Scotland means that collaboration, sometimes difficult to organise, is therefore doubly important.

“When National Museums Scotland first approached us in 2018, they already had a strong track record of working with museums across Scotland but this project provided a first-time opportunity to appoint a curator to work with natural science collections.

“Behind the proposal we detected genuine two-way partnerships welcomed by museums where advances in curatorial knowledge and collections care could enhance public engagement with their fossil collections.

“Three years later the impact of the grant has been significant. The project’s legacy is felt first and foremost by the partners, where the profile, skills and visitor engagement in relation to partner institutions’ fossil and Natural Sciences collections has been strengthened.

“Beyond the participating museums, there has also been a tangible benefit for the museum community more widely by making the resulting resources available online.”

Scotland’s key role

Scotland’s varied geology and long history of fossil collecting mean it has had a key role in our understanding of the development of our planet over millions of years and has provided crucial evidence for significant changes over time and indeed for the theory of evolution itself.

As far back as the 1700s, geology was studied by eminent scientists of the day, notably James Hutton (1726-1797) whose ideas, based on his observations of Scottish geology, provided the foundations for geology as a modern subject.

For example, Hutton proposed the concept of deep time based on his observations of tilted layers of rock at several localities across Scotland, most notably Siccar Point, East Lothian.

Rocks across Scotland range from the Lewisian gneisses of the northwest, representing metamorphosed rocks from over four billion years ago, to the post-glacial clays of the Clyde and Tay estuaries, dated to 13,000 years ago and indicating the presence of a cold Arctic climate.

Almost every geological period between is represented by some form of sedimentary, igneous or metamorphic rock, indicating settings as diverse as desert sand dunes, swamps and great lakes, with tectonic events resulting in continental collisions, mountain building and the opening of oceans at different times.

Scottish fossils and geology also informed and inspired the work of many other prominent natural scientists including Charles Lyell through to more recent discoveries such as dinosaur bones on the Isles of Skye and Eigg.

Through scientific study, it’s known several of the fossil-bearing rocks of Scotland represent key stages in Earth’s history, such as the early ecosystems in the Devonian (419.2 million years ago, to 358.9 Mya) and the Carboniferous (358.9 million years ago, to 298.9 Mya) transition from life in water onto land.

Scottish fossils have helped to fill gaps in the fossil record, notably an interval known as ‘Romer’s gap’ in the Early Carboniferous and a rare glimpse of Middle Jurassic terrestrial life from 174.1 to 163.5 million years ago, including dinosaurs and early mammals.

The fossils of Scotland have also played a crucial role in historic scientific discussion.

For example, the distribution of fish and reptile fossils from Elgin, Moray, led to the separation of the Devonian ‘Old Red Sandstone’ from the Permo-Triassic ‘New Red Sandstone’, at the same time providing support for the then recently-proposed theory of evolution.

Courier Country collections

Perth Museum and Art Gallery holds 1,890-2,000 fossils in total.

The fossil collection includes 350 specimens of plants, eurypterids, fish and mammals from the Devonian, Carboniferous and Pleistocene of Angus, Perthshire and Fife, a collection considered to be important by palaeontologists studying the localities and fossils following numerous loans for research purposes.

Material from the Lower Devonian of Balruddery Den, preserving a range of invertebrate, vertebrate and plant fossils, is extensive and otherwise present only in the National Museums Scotland and The McManus: Dundee’s Art Gallery and Museum collections.

The fish are especially important for their diversity and range with examples of Cephalaspis, Mesacanthus and Parexus.

The McManus in Dundee has 2,500 fossils.

The collections have a focus on several stratigraphic levels exposed locally, although fossils representing the Devonian are noticeably numerous.

Samples of the Aberdeenshire Rhynie Chert contain the early plants Psilophyton and Rhynia.

Lower Devonian fossils from Turin Hill, Angus, illustrate another ecosystem deposited within the Forfar Basin.

Between 800 and 1000 fossils are housed at Montrose Museum.

Collection highlights include Lower Devonian fossils, linked to Reverend Hugh Mitchell (1822-1894); fossils from localities on land owned by Lord Kinnaird (9th Lord, George Kinnaird, 1807-1878); Arctic clay fossils collected by James Cunningham Howden (1830-1897) and Robert Boog Watson (1823-1910); fossils of the Munich Collection and fish fossils from the Devonian of Abergavenny, Wales.

Meanwhile, the Fife Collections Centre is managed by Fife Cultural Trust on behalf of Fife Council.

It comprises 2,000 fossils including fossils from the Fife area; fossils linked to Reverend John Anderson (1796-1864), Robert Dunlop (1848-1921), Reverend Dr John Fleming (1785-1857), James Wright (1876-1957), J Wood and D Nevey and fossils forming part of the Lauder Collection.