There is something special about kestrels – small and sleek falcons with an underlying charisma that makes them totally addictive to watch.

As such, I jumped at the opportunity when Tom Bowser of the Argaty Red Kite Centre near Doune, Stirlingshire, invited me along to a session ringing young kestrels.

Kestrels have declined over the last few decades and placing marked rings on their legs plays an important role in tracking their movements and behaviour, thus aiding their conservation.

At Argaty, the good news is that kestrels are on the increase, probably because the placement of nest boxes has boosted their fortunes.

Nest boxes

When Tom first started erecting nest boxes in trees in 2018, there were only two pairs nesting.

This year that number has soared to four, an upturn that clearly delights Tom, who has a particular soft spot for kestrels.

“They are stunningly beautiful birds and have a special attraction that is totally compelling,” he says.

I know exactly what Tom means, and I believe it is the exquisite body lines, so slim and beautifully proportioned, combined with the intricate plumage that is at the core of this allure.

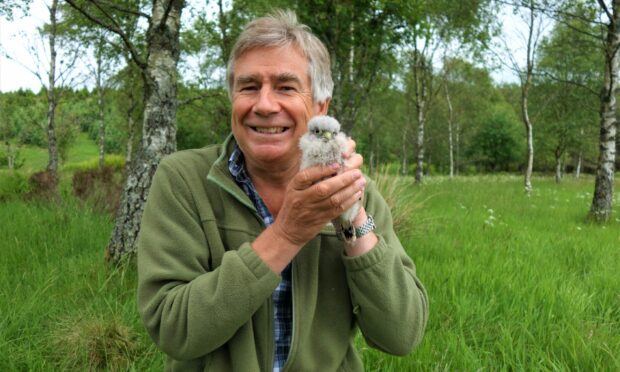

Accompanied by expert bird ringer, Keith Burgoyne, and his grand-daughter Holly, it was with great anticipation that we set off to a nest box in woodland near Argaty, where Tom knew there were chicks of a size ready to be ringed.

The nest box was roofed and enclosed, with a large entrance at the front to enable access for the falcons.

Predators

Kestrels often breed in old crows’ nests, but their success tends to be higher in nest boxes, because of the shelter provided from both weather and predators.

Tom deftly climbed the tree to the nest box, and then gently placed each kestrel chick into cloth bags, before being lowered to the ground.

Numbered and coloured rings were carefully secured around the legs of each bird and the youngsters were weighed and measured, before being returned to the nest.

The chicks were small bundles of perfection, still fluffed with down but the first signs of their adult feathers emerging.

Their eyes were keen and piercing, so essential for their future survival when they need the ability to detect the smallest tell-tale movement of a vole or insect on the ground from high up in the air.

Many theories have been put forward for the decline in kestrel numbers, including changes in farming practices and blanket afforestation reducing the open spaces that kestrels need to hunt.

The increase in buzzard numbers in recent decades may also be partially responsible – either through increased ecological competition or even direct predation.

Most likely, it is a combination of these and other more subtle factors that are behind the fall.

One thing for certain, however, is that the crucial study work being carried out by Tom, Keith and their compatriots in raptor groups all around Scotland will help ensure our precious kestrels continue to soar in our skies.

INFO

An adult male kestrel has a blueish-grey head, rump and tail, while the female has brownish upperparts and tail, both of which are barred black.