The life of a climate science pioneer who was born into relative poverty in Perthshire is being celebrated in a new children’s book.

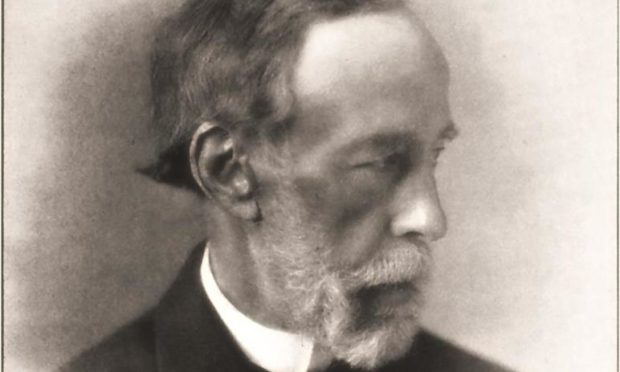

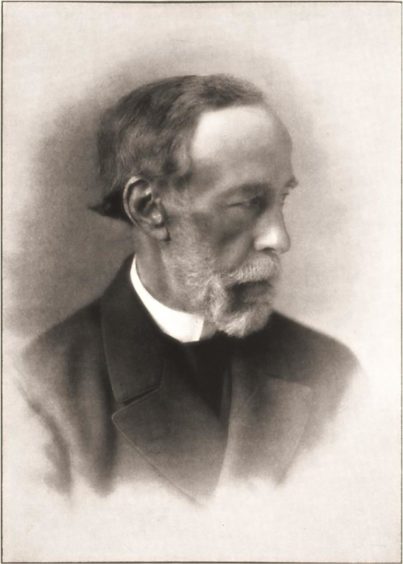

‘James Croll and his Adventures in Climate and Time’ written by Jo Woolf and illustrated by Dylan Gibson, tells the compelling story of James Croll (1821-1890), who is considered to be one of the world’s first climate scientists.

Raised in an impoverished crofting family with little access to schooling, James Croll was almost entirely self-taught, yet he helped us to understand why the ice ages happened, and how they could be predicted.

He was the first to consider the role of feedback loops in climate systems such as the albedo effect.

The book was initiated by the Perth-based Royal Scottish Geographical Society (RSGS) to mark the bicentenary of Croll’s birth – as featured in The Courier – and bring attention to his work as a Scottish climate scientist in the run up to COP26 in Glasgow later this year.

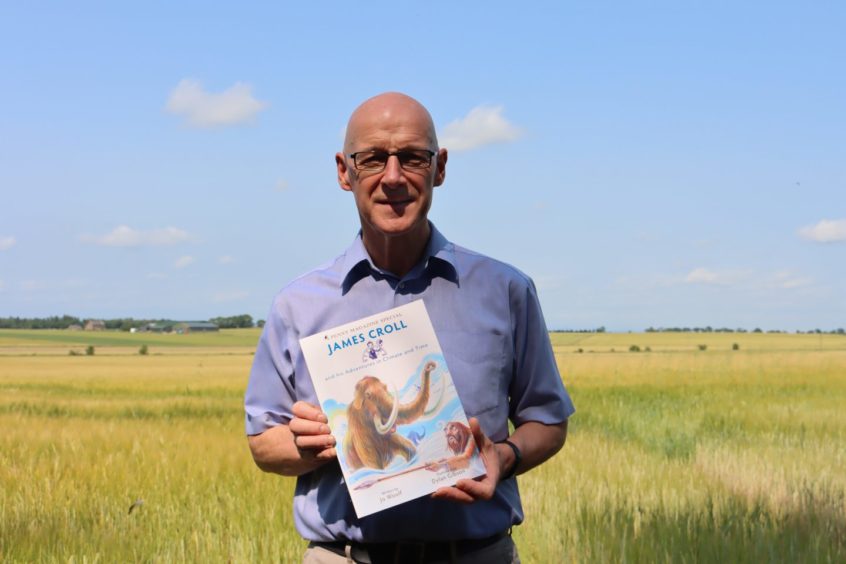

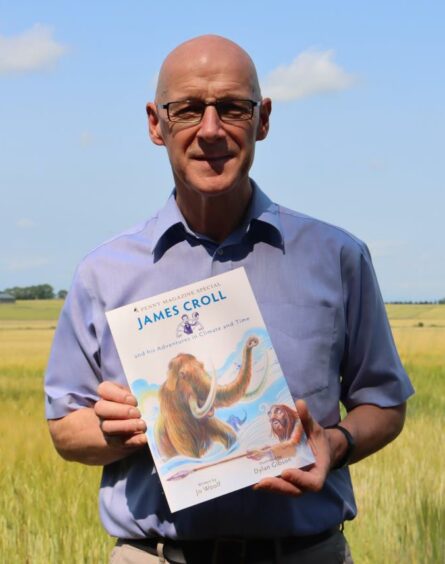

Commenting on the project as Deputy First Minister John Swinney helped launch the book, RSGS chief executive Mike Robinson said: “James Croll is one of the most significant, yet least heard of, figures in the field of geological climate science.

“This story could not come at a better time. With the eyes of the world on Glasgow, it is a reminder that Glasgow is not just the seat of the industrial revolution, but was also home to scientific discovery and learning.

“With the approach of COP26, his bicentenary is a great opportunity to showcase Croll’s and Scotland’s immense scientific contribution.

“This beautifully illustrated book has done a wonderful job of bringing Croll’s extraordinary story to life, perfectly explaining some of the science behind his theories, whilst also capturing his journey of discoveries.

“I believe that this book will inspire a new appreciation of Croll, not just as a scientist but as a remarkable human being.”

Mr Swiney added: “James Croll’s research into climate change was ground breaking, and inspired generations of scientists in the decades that followed.

“It is a source of enormous local pride that a man who has contributed so profoundly to our collective understanding of the world was born in Perthshire, and I am therefore delighted to support the publication of the Croll book.

“For centuries, Scotland has been at the forefront of scientific research and achievement, as we approach COP26, it is vital that we harness this academic ingenuity so that Scotland may take a leading role in the fight against climate change.”

Humble beginnings

Early in his life, Croll worked numerous manual jobs- most notably as a janitor at the Andersonian College in Glasgow, where he sat in on lectures and had access to a library of books which inspired some of his theories.

Croll applied his mind to some of the biggest questions of his generation: the age of the sun, the source and direction of ocean currents, the thickness of the Antarctic ice sheet, and the cause of the ice ages.

Croll eventually gained a position with the Geological Survey in Edinburgh and released his book ‘Climate and Time’ which gained him prominence amongst the most notable scientific minds of the day.

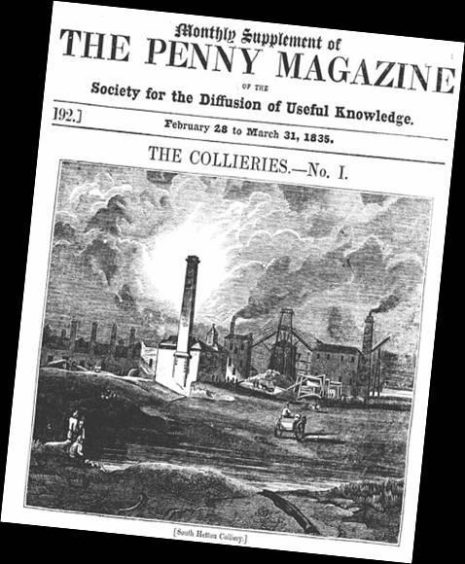

The inspiration for this children’s book’s format comes from a popular 19th century publication called the Penny Magazine, first published in 1832 which played such a key role in firing his young imagination; Croll became an avid reader at an early age, and later attributed his thirst for learning to the magazines wide-ranging articles.

Commenting on the experience of writing about James Croll’s life and discoveries, author Jo Woolf said: “It was such a fun experience to write the book, particularly as I was able to start almost from scratch and imagine Croll as a youngster, full of curiosity and enthusiasm.

“Dylan’s images are so lively and appealing and full of character.

“They sparked new ideas when I saw them, and that’s how the book progressed – working together, we were able to develop the text and the images alongside each other.

“I discovered some elements of Croll’s character that I had overlooked before – his determination and tenacity, and his ability to daydream which took him away from the awful challenges he faced.

“He absolutely refused to give up his passion, which was studying and pondering the big questions of the universe, and I find that really inspiring.”

The book has also been printed as free resource for schools with an accompanying lesson plan, set to be distributed in the autumn.

James Croll bicentenary

As featured in The Courier on the bicentenary of his birth, James Croll was born on January 2 1821 to David Croll, a stonemason and crofter, and Janet Ellis, formerly of Elgin, in the hamlet of Little Whitefield, about five miles north of Perth.

The family were forced to move when James was three years old after the croft was cleared by the landowner Lord Willoughby.

Some families were encouraged to relocate to Burrel Town, a mile or so east, and others were offered an area of derelict bog-land a mile or so west, in some sort of recompense for being displaced.

This latter area became the village of Wolfhill and here James’ father managed to clear between four and five acres and build their own house.

Having previously farmed an area of closer to 20 acres, as Croll’s family had for at least the previous 200 years, it was not possible to feed the family from such a small land-holding, so James’ father had to revert to his trade as a stonemason and travel regularly away from home. It therefore fell to James to farm the land.

But James was afflicted with a pain in his fontanelle which would have required him to wear a hat in class to keep his head from hurting.

This was enough to put him off attending school, so up to the age of eight he was schooled in part by his parents, occasionally by a visiting school teacher, but in main by his elder brother Alexander.

Unfortunately Alexander died at the age of 10, and James was forced to attend school himself from that point onwards.

James, whose younger brother William had died two years earlier at a few months old, attended school in Guildtown from the age of nine.

But he found the teacher to be “too tyrannical”, says Mike, and did not fare well.

When he finally left, aged 13, to help manage the croft, by his own admission he was below the average student.

But it was around this time that he stumbled upon the monthly ‘Penny Magazine’ of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge in a shop in Perth and suddenly his intellect was unleashed.

It was at this time that a leading Swiss scientist, Agassiz rocked the Swiss geological community by first reporting his theory of glaciation at a conference in Neuchatel.

Up until this time most scientists believed that massive rocks, which had travelled large distances from their source had been washed there in the biblical floods that Noah survived.

The idea that glaciers covered larger areas and had deposited rocks there but had now retreated was controversial and widely disputed, but it was Agassiz in 1837 who first formally presented this theory.

A deeply religious man who worked as a joiner to help build his friend, the Reverend Andrew Bonar’s new Kirk at Kinrossie (now the village hall), Croll moved to Glasgow and then Paisley where he continued to work as a joiner for three years, until 1846, when his elbow became ossified and he was forced once again to return to Wolfhill.

He began working for Bridgend coffee merchant David Irons in Perth for some months, before Irons set him up in business in Elgin with his own shop.

Whilst in Elgin he met and married Isabella MacDonald from Forres who helped him with the shop, but within three years, he became ill and unable to work and was forced to sell it and move back to Perth.

Temperance

Staunch tee-totallers, he and his wife established a Temperance Hotel in the Well Meadow in Blairgowrie, but it was perhaps predictably unsuccessful and he once again had to sell up.

He then worked as an insurance salesman in Dundee, Edinburgh and then Leicester, but, as a retiring and modest man, was never comfortable in the role.

This time it was his wife who became seriously ill, and they were forced to move back to Glasgow where her sisters could help with care.

Croll took some time at this stage to produce his first book, “The Philosophy of Theism”, and tried his hand as a journalist on a temperance newspaper in Glasgow.

Then finally, at the age of 38, in an age when the average life span was barely mid-40s, he finally got the lucky break he needed.

Paid just £1 a week (equivalent of £3,500 salary today), plus taxes, coal and a house, he got a job as a janitor at the Anderson College in Glasgow.

But he was the happiest in his work that he had ever been as he now had access to the extensive library.

Fairly quickly he began to develop more and more scientific papers.

Critical papers

In 1864 Croll waded into the glacial debate and wrote a critical paper for the Philosophical Magazine : “On the Physical Cause of the Change of Climate During Glacial Epochs”.

He proposed that there were in fact several ice ages and that they were brought about in part by changes in the orbit of the Earth round the sun; the tilt of the Earth in space, particularly in relation to the different seasons; and by the ‘wobble’ of the magnetic poles over time.

This began a period in which Croll corresponded regularly with many of the greatest scientific minds of the day including Darwin, Tyndall, Lyell, Wallace, Lord Kelvin, Joseph Hooker and Fridtjof Nansen.

In 1867 he was persuaded by Archibald Geikie to join the Geological Survey of Scotland.

In 1875 he published his most critical work, the distillation of his theory of ice ages and earth’s orbit, called “Climate & Time”.

In 1876 – the year his only surviving brother David died – he was made a fellow of the Royal Society, an Honorary Member of the New York Academy of Sciences and he was awarded an Honorary degree by St Andrews University.

However, forced to retire early aged 59, from the continuing ill health that had so plagued his life, he was forced to move into rented lodgings in North Methven Street in Perth after failing to get an enhanced government pension.

He was later given a monetary ‘gift’ by the Geological Society which allowed him to see out his days in a house at 5 Pitcullen Crescent in Perth.

James Croll died on December 15 1890 and is buried in Cargill churchyard on the banks of the Tay, close to the area in which he grew up.

In all he produced 92 scientific papers, wrote four books and although elements of his theory were incorrect, he opened the door to an understanding of the links between the sun and the Earth’s climate, paving the way for Milutin Milankovitch (1879-1958) and others to refine and develop his thinking.