A revival of the old Scottish tradition of hutting could have widespread benefits.

“It’s just good for the soul to have a little place to call your own, that you can get away to whenever you want.”

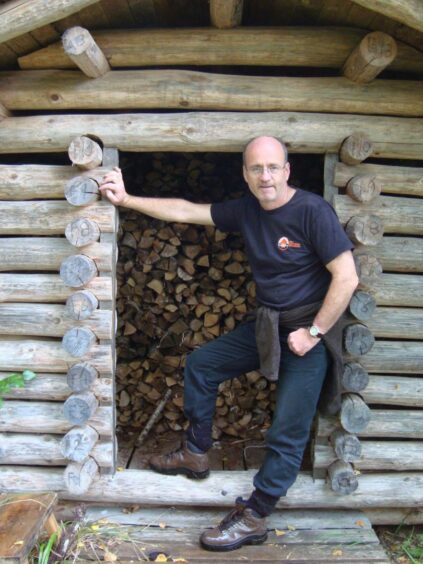

Donald McPhillimy leads Reforesting Scotland’s 1000 Huts campaign.

He is enthusiastic about the benefits of hutting.

Popular in Nordic countries, hutting was once more widespread across Scotland.

But cheap flights and the lure of warmer climates led to woodland retreats being abandoned.

Donald now hopes a pilot scheme in Fife will reintroduce people to the simple pleasures of retreating into nature.

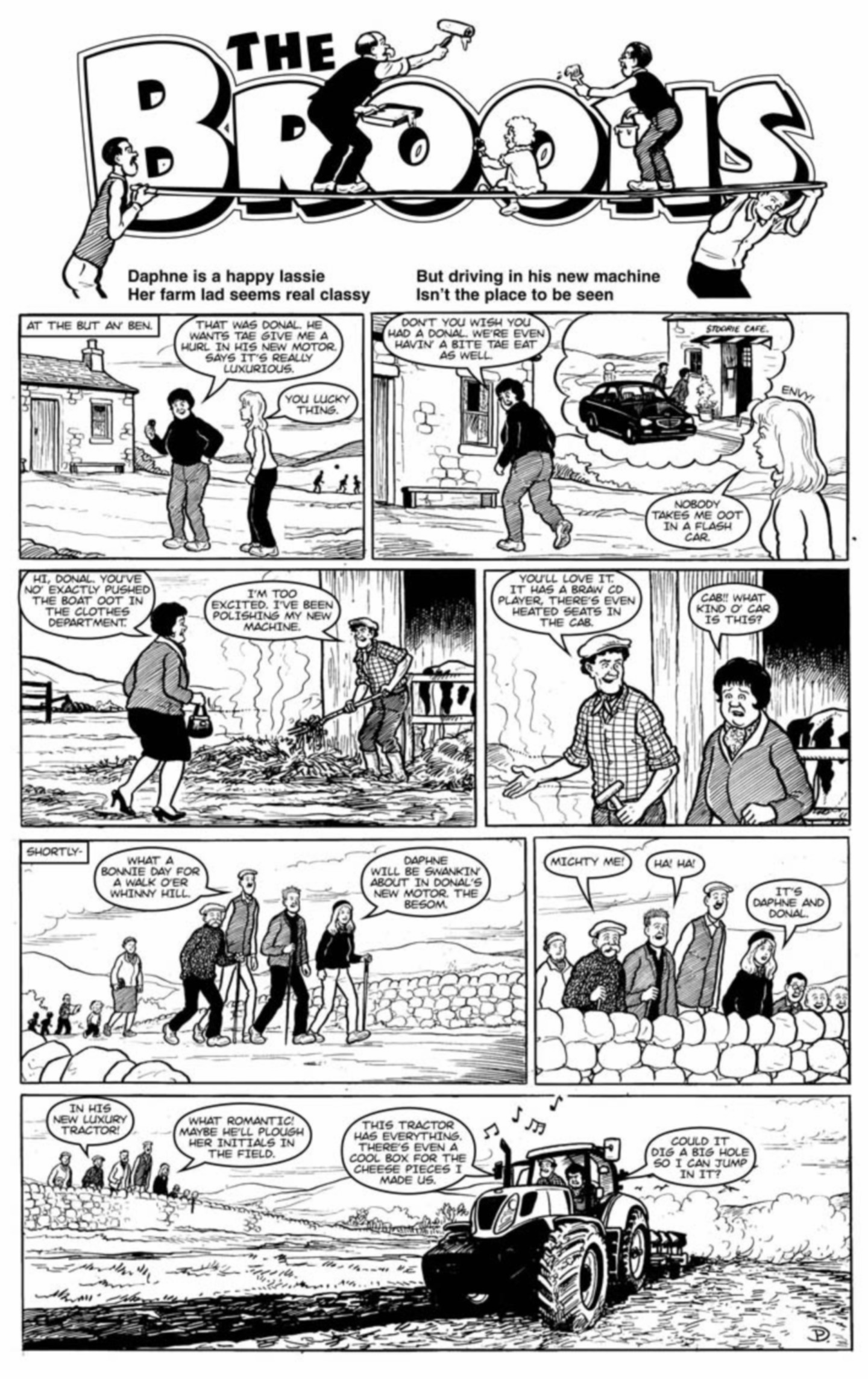

What is hutting and what does it have to do with the Broons?

After the First World War, workers from industrial towns could rent a little patch of ground and build a hut they could escape to during weekends and holidays.

It got them out of polluted urban areas and close to nature. It was somewhere they could connect with the outdoors and relax.

Think about the Broons holidaying in their wee but an’ ben.

They may have been crammed into a Dundee tenement flat, but even the comic book favourites could afford to escape to the country.

And that is exactly the point, says Donald.

“The Broons used to go off to the countryside and stay in their but an’ ben.

“The but an’ ben was a stone building, a stone farm cottage, and we’re talking about wooden huts.

“But it was the same idea.”

Donald says the 1000 Huts campaign is determined hutting does not turn into something for the middle class and affluent.

“Because huts are low impact and affordable, lots and lots of people can buy into this and get the benefit from it.

“It’s open to everybody.”

What’s happening in Fife?

There are hutting sites around Scotland.

But for decades there were no efforts to create new hutting sites as cheap flights made jetting off on holiday a more attractive prospect.

By taking over a Forestry and Land Scotland site near Saline in Fife, 1000 Huts hopes to change that.

Twelve families have now signed up to become hutters at Carnock Wood.

Aside from an access road and car park, Donald says the huts will have minimal impact on the woodland, and may even improve it.

“It’s a lovely bit of woodland next door to where the huts are going to be.

“It’s a bit of mature birch woodland, which is already quite well used by local people, which is not going to change.

“The woods are full of little pathways and clearings. It’s nice airy woodland. It’s just an ideal place for kids to play.

“I would expect that over time the hutters would take on projects within the forest.

“They might be interested in thinning an area of woodland, planting some more native species or digging out a pond.”

Shanty shack or classy cabin, the choice is yours

How much you spend on your hut is up to you.

You could throw up a hut for a few hundred pounds, or you could splash out thousands on a luxury lodge.

However, huts should cover an area of no more than around 300 square feet and be built in a way that allows them to be removed completely once no longer fit for purpose.

You should expect to live without mains water and electricity, and use a composting toilet.

And you can’t live in it all year. Use has to be ‘intermittent’.

Since 2014, Scottish Planning Policy has recognised hutting.

The move has opened the door for more people to build their own huts.

Planning permission is still required, but conditions have been set out which exempt hutters from certain building regulations.

Could hutting help save the planet?

The coronavirus pandemic led to a surge in staycations.

And then we have the long-term reality of climate change.

“The whole future of international travel, there’s got to be a big question mark against that,” said Donald.

“From the carbon point of view, we can’t afford to be flying here, there and everywhere.

“We can’t go back to that.”

He hopes Scotland can become more like Norway and Finland, which already have a thriving hutting culture.

“They go fishing and collecting berries. They’re really connected with nature and they’ve got a far better attitude about nature than our poor urban population who hardly ever see a blade of grass.”

He said allowing urban dwellers to “connect with the land” could boost mental health and address social issues.

“It’s harking back to innocent times.

“In the old days kids just went and played and made dens. You didn’t see them all day.”