Gayle takes part in an archaeological dig in hope of finding the ‘lost Monastery of Deer’…

As I grub around in the earth, sweating in the heat of the midday sun, I feel ever so slightly like Indiana Jones.

But unlike the charismatic, fedora-clad archaeologist, who was searching for a lost ark in the Peruvian jungle, I’m looking for a lost monastery – in Aberdeenshire. I’m not the first, and the chances are, I won’t be the last.

Archaeologists have long tried to identify the precise location of the elusive Monastery of Deer, which is believed to be the place where medieval monks penned possibly Scotland’s oldest surviving manuscript – the 9th Century Book of Deer.

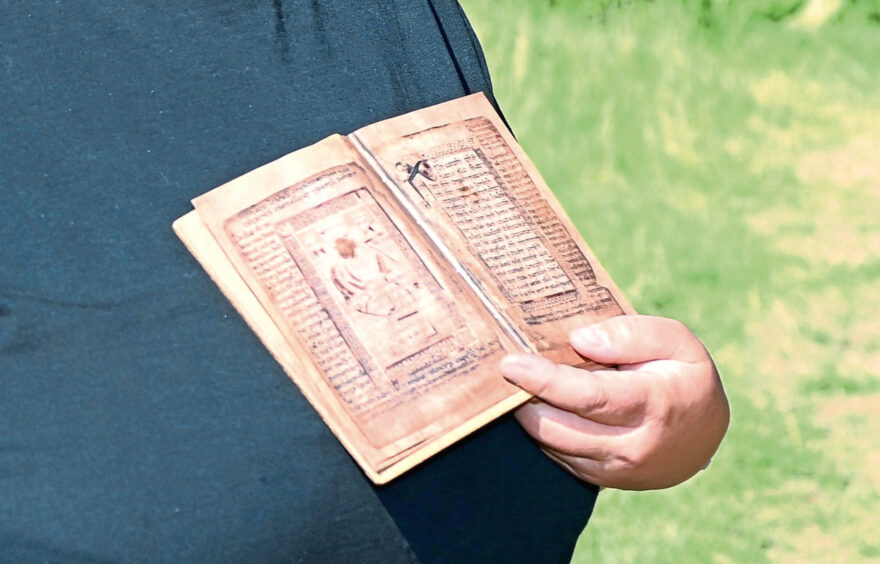

Exquisite little book

This exquisite little book has been described as one of Scotland’s greatest treasures and is on display in Aberdeen Art Gallery until October 9, on loan from Cambridge University Library.

The margins of the rare book, which Book of Deer archaeologist Ali Cameron calls a “pocket gospel”, intended for private reading and prayer, contain the earliest surviving written examples of Scots Gaelic.

The notes describe the founding of an early monastery by St Columba and mention places like Deer and Aden.

Keep on digging

I’ve joined a dig for the monastery as part of the Book of Deer Project 2022, and while I have no clue what I’m digging for, Ali is happy to fill me in.

“Unfortunately there’s no information about what the monastery looked like or where it was exactly,” she tells me.

“We’ve done many digs around the Aden and Old Deer areas and have been working, on and off, on this site in the field to the west of Deer Abbey since 2017.

“We’ve already uncovered an early medieval site, with charcoal and holes for wooden posts dating back as far as 650-750 AD, but we’ve yet to prove this was the monastery. It’s possible it was, but we’d love to know for sure.”

Ali shows me a model of the Book of Deer and it’s absolutely fascinating. “See where it mentions ‘Malcolm?’,” she says, pointing to the manuscript.

“The text talks about the foundation of the monastery, around about 1000. The problem is it doesn’t say where it was, how many people were here, what it did and so on.

“The margins include mention of land grants which talk of Deer and Aden and only recently did scholars at Cambridge University realise it was linked to Deer Abbey.”

All the signs

When Ali was first employed as Book of Deer archaeologist in 2014, she walked round a field close to the abbey and deduced that it could be the site of the monastery.

“There was a river at the bottom, a wood, and everything that would’ve been needed to make a monastery. We did a geophysical survey and worked out that this is a sort of ‘artificial’ area.

“It was cultivated by Admiral Ferguson who took ownership of Deer Abbey and made it his folly.

“He destroyed a lot of buildings through agriculture and cleared out all the skeletons from the abbey to make way for his own mausoleum.”

Fascinating fragments

Discoveries include hearths, charcoal and pottery fragments – “the sort of pottery monks might have used at the time”, says Ali. The fragments have been dated between 1276 and 1395 – when the abbey was likely in use. The charcoal dates between 1147 and 1395.

Archaeologists also recently found industrial waste (slag used in furnaces), water channels and a stone drain, which could be evidence of mill buildings, and a ditch.

“When you find a ditch you get really excited,” says Ali.

“When Columba came here he was trying to convert the Picts to Christianity. There was no consecrated ground so they would build a ditch round the consecrated area… possibly a monastery.”

Another interesting aspect is a path. “We wonder if it took people from the monastery somewhere” says Ali. “Or was it to keep people from wet ground? It’s really well-laid and what we’d expect in a monastery or abbey.”

I get stuck in, digging in a trench and while cautious I might destroy some ancient relic, Ali assures me I won’t.

Use your imagination

Meanwhile, volunteer Gayle Burgoyne is busy trowelling an area. “We’re scraping off a centimetre of soil and looking for anything unusual – any lumps of charcoal or bits of slag,” she says.

“You have to use your imagination and visualise what could’ve been here. This could’ve been a working metal area – there’s a hearth and we’ve found slag and metal. There are indications of a possible monastery but nothing conclusive… as yet!”

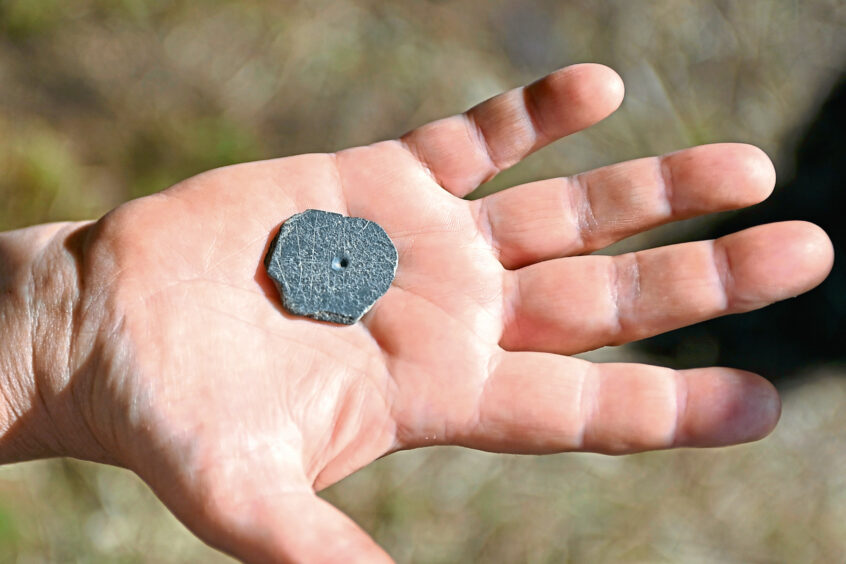

Rory Smith is on a placement from his degree in ancient Mediterranean civilisations at Edinburgh University. “I found a bit of copper – I was completely dazzled by it,” he says. “I was told it might be part of a clasp.”

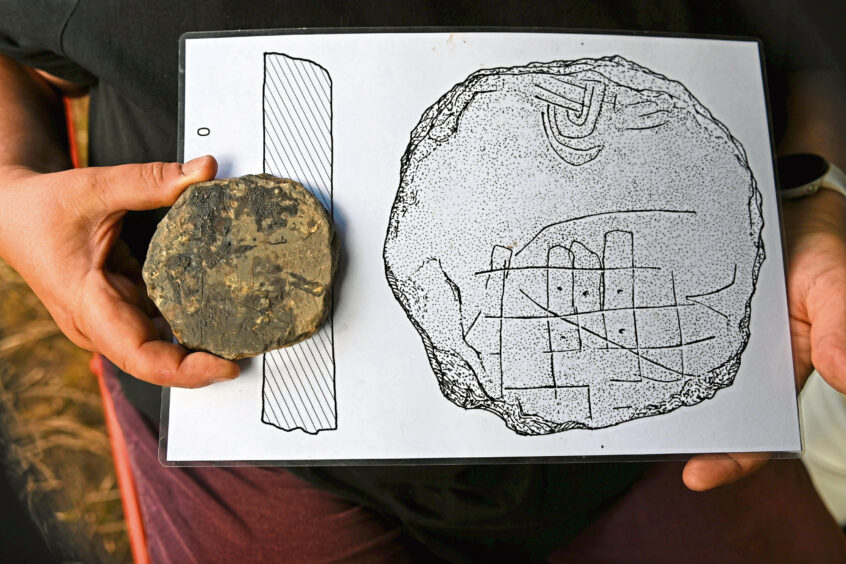

Games board

The discovery of a rare games board at the site in 2018 was hugely exciting, although Ali hoped it might be medieval.

“We immediately went, ‘wow’, but then a medieval games specialist said it could date from 500 to 1500.

“Monks likely used the board to play Hnefatafl, a game like Nine Men’s Morris. It’s essentially a stone with a game board scratched on it.

“There’s also a ‘Solomon’s knot’ scratched on which is medieval graffiti to ward off the devil.

“There would’ve been counters, or tiny little pieces, to play with. The stone is very thick and would’ve once been a roof tile, either on the monastery or abbey. It’s so small, for people travelling – a bit like travel scrabble.”

Only a few such boards have been found in Scotland, on monastic or religious sites.

The dig continues until September 9 and volunteers are encouraged to get in touch.

You never know – you could find a conclusive piece of evidence to suggest that this WAS the site of the lost monastery. And wouldn’t that be amazing.

- The Book of Deer is on exhibition at Aberdeen Art Gallery, along with a programme of events, until October 9.

- For info on archaeological digs, see The Book of Deer Facebook page.

- All recently-excavated soil from the Deer site will be sent off to Aberdeen University for analysis.

Conversation