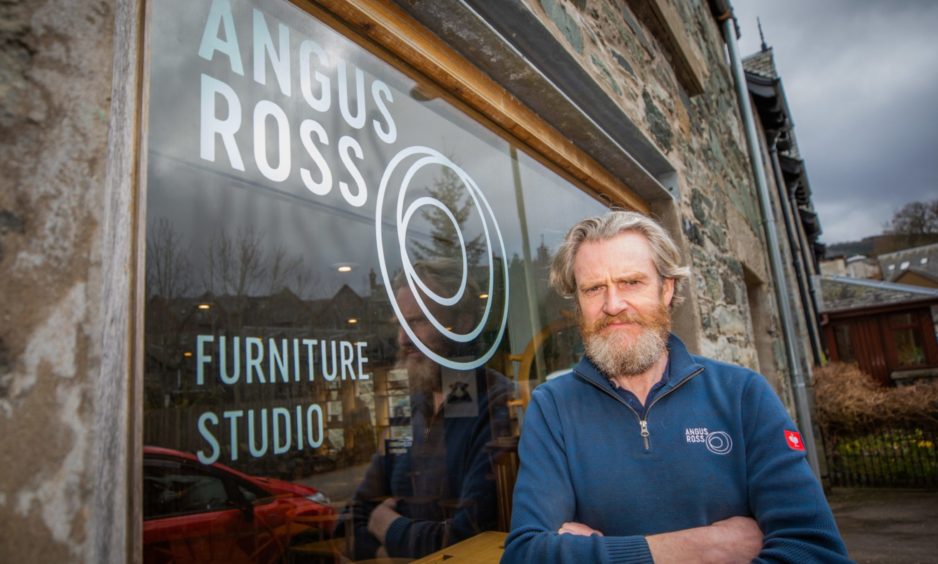

Ahead of the ‘world’s greatest flower show’, Michael Alexander speaks to Perthshire’s Angus Ross about the growing appeal of sustainable furniture-making and his signature steam-bending technique.

If Aberfeldy craftsman Angus Ross wanted to sum up events of the last few years, then he could do worse than go with ‘in the middle of every difficulty lies opportunity’.

Making use of fallen trees

After Storm Arwen knocked down thousands of trees in Perthshire and beyond in 2021, he approached local estates and was granted permission to use some of their fallen timber.

But being forced to temporarily abandon his workshop during the first Covid-19 lockdown in 2020 has also proved fortuitous.

He started to make a few one-off garden furniture pieces on his own.

Using his signature steam-bending technique, it has led to the design of a curvaceous new garden range including a chair, bench and table which will be presented to the “world’s greatest flower show” – RHS Chelsea – from May 22 to May 27.

Why enter the show?

Last year, Angus and his wife Lorna went down to the show to “see what it was like”.

While they enjoyed it, and noting that ‘Rewilding Garden’ won best in show, they could see how little garden furniture was made from low-carbon truly-sustainable material.

Keen to promote their ethos of working with local wood and making furniture locally, they fired in an application for 2023.

Despite people warning them the event would be oversubscribed, they were delighted to be accepted!

Describing their attendance as “quite a coup”, Angus told The Courier that the first special edition of the new garden range is being made from ‘Dalcapon Oak’.

Two large oak trees were going to be felled on a farm near Pitlochry.

They were contacted by the farmer who asked: “Did we want the wood?”

The second special edition of Dalerb Furniture will be made from Fortingall Oak.

Three large oak trees blew down on Glen Lyon Estate by Fortingall, six miles from the workshop, during Storm Arwen.

“We are often offered trees by local foresters, tree surgeons, farms and estates and if we can use it, the next step is to call in saw-miller Pol Bergius with his mobile saw-mill to cut the timber into planks,” said Angus.

“These trees were particularly straight-grained and provide wood that is perfect for steam-bending.

“We are using this wood to create components for our first edition of Dalerb Garden Furniture for RHS Chelsea.

“There is zero-waste as any wood we can’t use are cut into firewood or chipped for mulch.

“We are delighted to be part of a local circular economy of highly skilled and passionate people looking after our precious native trees and woodland.”

Importance of sustainability

Angus explained that preparing oak for their garden furniture is almost zero carbon.

They store the planks of wood ‘in-stick’ at a yard in Aberfeldy.

The air dries the wood to prepare it for furniture making.

Some oil is required for felling and milling and the 15-mile transport to their workshop.

But using wood is elemental.

Sunlight and photosynthesis grow their material.

Air then dries it to prepare it for furniture making.

Their machines, powered tools and steam-box are run on renewable electricity.

But most importantly they use steam and human power to coax raw wood into fine furniture.

The furniture is hand-made in their studio-workshop.

“Once all the components are made the next step is to join them,” said Angus.

“There is a great attention to detail and we use traditional joint work to create beautiful, robust and durable furniture.

“The frame of the Dalerb chair has seven components plus the curved back-rest and slatted seat.

“A sliding dovetail joint joins the front rail to the centre-rail below the seat.

“A bridle joint joins the arm-rest to the front leg.

“A pegged mortice and tenon joins the front-rail to the front leg.”

How Angus became a craftsman

Born in Edinburgh in 1963, Angus Ross was brought up in Inverness, before returning to the city he loves to study at Napier University in 1981.

After Napier, he spent eight years as a designer at Mothercare and a spell doing voluntary work and travelling in Africa and South America.

But disillusionment with the mass market inspired him to retrain as a carpenter.

Although Edinburgh still holds a place in his heart, he swapped the buzz of the city for the peace and quiet of rural Perthshire – finding joy in creating bespoke furniture.

A furniture maker since 1992, he has been based in Aberfeldy since 2003.

In 2004 they joined a collective – including native tree foresters and a saw-miller.

They bought Old Castle Wood, a 50-acre bluebell wood a few miles downstream from their workshop.

This began a relationship with this special area of ancient semi-natural woodland.

During the 18th and 19th centuries, the wood was planted with oak to be coppiced for bark: an essential ingredient for tanning leather.

With the rise of chemical tanning, oak was no longer required, and post-First World War, the woodland became largely unworked.

In fact, when the woodland was sold in the 1980s it was recommended that the oak trees be clear- felled and non-native softwoods planted for commercial forestry.

Angus is delighted this didn’t happen!

Variety of habitats

“Our woodland with a variety of habitats including a rare damp natural ancient alder wood is the sort of landscape now envisioned in re-wilding projects,” he said.

“We manage the wood to improve biodiversity, improve the future quality, health and resilience of trees, and improve access and amenity use for ourselves and others.

“We practice highly selective felling to improve the quality of the remaining trees by providing them with more light and room to grow.

“Allowing more light onto the woodland floor also helps natural regeneration and increases the under-storey of plants and bio-diversity.

“As part of our selective felling we often fell spindly, bent and gnarly old trees producing small section, short-length timber.”

Angus explained that he could not initially see how to use this timber for fine furniture making.

However, in 2005, he explored steam-bending for a large public art commission (Cafe Furniture for Avon and Wiltshire Mental Health Trust) and the connection was made.

This began a love affair with steam-bending and led to many innovations and awards.

Steam-bending technique

“We now use Old Castle Wood timber for steam-bent interior furniture products sold in our on-line shop and for one-off exhibition pieces at international art fairs,” he said.

“Working the wood helps preserve and improve our ecologically valuable and rather rare ancient semi-natural woodland.

“The workshop helps our woodland and the woodland helps our workshop.

“’Working Woods’ are happy woods and we are licensees of the Scottish Working Woods label.

“We are proud that by using trees from across Perthshire, for fine furniture making, we make a valuable contribution to the local economy involving tree surgeons, estate managers, saw-millers, some foresters and farmers.”

Angus adds that the beauty of garden furniture is that they don’t have to kiln dry all the wood because it’s going to be placed outside.

It means they can use the wood more easily and more quickly.

They always use oak trees for outside furniture because it’s such a durable timber.

There’s also growing public interest in the origin and life cycle of the product.

“That’s where timber comes into its own really,” he said.

“The worst case scenario is you can burn it in a fire.

“It’s a very sustainable material from that point of view!

“It doesn’t have much waste aspect. And the timber itself can be recycled.

“Because we produce in a very traditional manner, they can be repaired and if they get marked they can be sanded down.”

Craft and design

Having stated off as a designer, design is something that remains “key” to the way he works now.

But craft is also important.

Angus is pleased to see more young people coming into the craft world and is an admirer of people who “think” like English designer Thomas Heatherwick.

However, he’s sadly not really in a position to take on apprentices.

“We probably get a letter a month from someone who wants to come and see if they can work with us,” he said.

“The issue is we are not really big enough to do that.

“What we do do is try to encourage people to come and work with us for a week or so or even a few days so that they can get a feel for it, to see if that’s the thing for them really.

“Because I do think it’s important that people can come and understand what we do.

“A lot of people have no understanding of the actual production and work really in the way of making things.

“Particularly what we do now – there’s a high level of craft and a high level of skill which takes a lot of time to get to!”

Conversation