Angus Ribena farmer Andy Husband fears the planet’s changing climate will damage his blackcurrant harvest this year.

He has been growing blackcurrants in Angus for more than 30 years and told me he is “concerned” to see his crop changing around him.

“We’re definitely seeing the effects,” he said.

“Blackcurrants need 2,000 hours under seven degrees in the winter.

“We are seeing more problems with milder winters.

“Blackcurrants have to get winter chill, and if they don’t then they won’t bud break properly in the spring.”

Andy said this can lead to uneven ripening and poorer crops.

“We’re getting more wetter spells as well, rather than cold.

“That’s not what we want for fruit.”

Chiefs at the soft drink giant Ribena are warning their “farmers are under greater strain than ever before” as they battle with the real world effects of climate change on their harvests.

While Andy said the conditions are significantly worse down south, he has noticed the impacts of local weather changes on his own crops.

Harvest time for blackcurrants runs from mid-July through August.

This month, heavy rainfall has burst some of the blackcurrants at his Angus farm.

Andy runs East Adamston Farm, near Muirhead on the outskirts of Dundee, with his son Fraser. They are one of Ribena’s four growers based in Scotland.

Around the world, temperatures are rising to dangerous levels.

The first death has been recorded in Texas as a result of extreme heat.

In Scotland, we may not be facing these life-threatening high temperatures, but climate change is still having real impacts on our lives in the UK.

Andy began to notice undeniable changes to the local climate in the last five years. Milder winters and wetter summers, caused by climate change, can impact the health of his fruit harvest.

And he is not alone in his concerns.

Ribena growers across the UK have climate change concerns

A significant number of blackcurrant growers who supply Ribena have the same concerns as Andy.

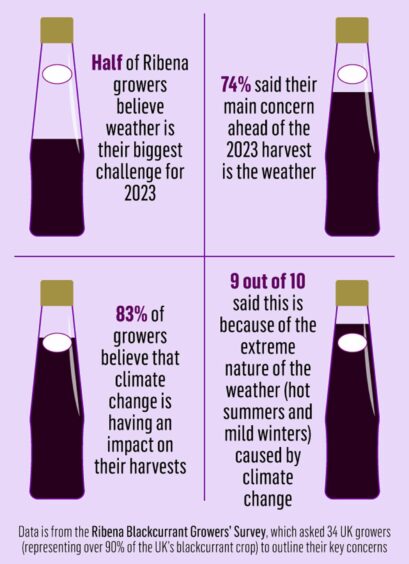

The Ribena Blackcurrant Growers’ survey asked 34 growers (who produce 90% of the UK’s blackcurrant crop) to share their concerns about their produce.

83% of these growers believe that climate change is having an impact on their harvests.

Liz Nieboer is head of external affairs and sustainability at Ribena maker Suntory Beverage and Food GB&I.

She said: “The long-standing connections we have with our blackcurrant growers are incredible. The average relationship goes back five decades and, in some instances, a remarkable 70 years.

“These close relationships mean we’re very close to the challenges facing our growers and what they need from Government to help. A combination of the threat of extreme weather and testing economic conditions means our farmers are under greater strain than ever before.”

Angus farmer praises work on climate change-resistant blackcurrants

Though Andy has concerns, the blackcurrant grower is more “confident” about his produce thanks to the work of local scientists.

Ribena has partnered with James Hutton Institute (JHI) to invest over £2 million to try to mitigate the effects of “increasingly extreme British weather”.

At JHI, soft fruit experts have been creating blackcurrant varieties that are resistant to climate pressures.

So what’s so different about these blackcurrant breeds?

- The blackcurrants need less of that winter chill (harder to get by with our increasingly milder winters).

- Common blackcurrant diseases are being bred out.

- These blackcurrants are tougher – literally. They have tougher skin and won’t break down as easily in a wet summer.

- They have a higher tolerance for spring frost.

Scientists at the James Hutton Institute have been breeding different blackcurrant varieties since the 1950s. The Invergowrie institution paired up with Ribena in the 90s.

With concerns about climate change impacts growing, they are working harder than ever to crossbreed soft fruit that can survive and thrive even in our changing climate.

Breeding programme ‘the way forward’ for blackcurrant concerns

Amanda Moura works as a soft fruit breeder with JHI. She will be speaking at the Fruit for the Future showcase in Invergowrie on July 27 to discuss JHI’s research.

She explained how blackcurrant breeding process works: “We find which is the best combination of crosses (blackcurrant crossbreeds) and then we develop those plants to combine their characteristics.

“We spend several years analysing them – at least six. After this, we take the cuttings to farm trials.”

For example, the scientists on the programme will select blackcurrant varieties which have larger leaves and growth habits which offer more of a canopy.

That way, the berries will have more shade and a greater protection against the heat from the sun.

“We’re adapting to the challenges that growers have,” Amanda continued.

“The whole soft fruit industry is already suffering the effects of climate change.

“There are direct impacts – the plants are already suffering with heat, and with very concentrated amounts of rain, as well as periods of [water] scarcity.”

As the whole trial process can take as long as 15 years, Amanda said they must always work “one step ahead” and pre-empt which issues will worsen in the future.

Back on the farm, Andy is hopeful that the programme at JHI will make a difference to the climate pressures blackcurrant growers locally, and all around the UK, are facing.

The challenges climate change poses are vast, but businesses like his are able to adapt.

He said: “There are blackcurrants which stand up to the changing conditions better now, thanks to the work at the James Hutton Institute.

“It’s been a great benefit to us to have such high calibre research on our doorstep.”