For the last decade, David Steel has spent nine months a year living and working on the windswept isle of May in the Forth.

His home on the Isle of May is a former lighthouse keeper’s cottage looking out over the North Sea and the island’s small jetty.

Sharing his picturesque but rugged and often challenging habitat are tens of thousands of seabirds – including the iconic puffin – seals, mice, rabbits and rats.

The Isle of May is five miles off the coast of Anstruther. It is a national nature reserve owned by NatureScot and an important centre for seabird and seal research. David is NatureScot’s reserve manager.

He admitted: “It’s not everyone’s cup of tea to live on an island.”

But for the dedicated ornithologist who has been fascinated by birds since childhood it’s paradise.

“I’d do this for nothing,” he said.

At the end of March each year, David, 47, says goodbye to his family and it is November before he returns for good.

He’s being doing this for 24 years. That includes 10 years on the Isle of May and before that 14 years on the Farne Islands, off the Northumberland coast.

David Steel’s life in remarkable Isle of May surroundings

His stint on the Isle of May begins as seabirds start arriving for breeding season and continues long after they have departed and seal pupping is underway.

He works long hours during the peak of the season from May to July, when he’s joined by up to 18 scientists, PhD students and volunteers.

But that’s rewarded for him by living in such remarkable surroundings at close quarters with his beloved birds. (Don’t tell the puffins but the razorbill is his favourite).

David said: “It is just an incredible place. I always have an early start to the morning to have an hour to myself and I walk around the island.

“You’re at one with nature and the island. It’s good for the soul.”

Whales and Northern Lights

From the patio of his cottage he witnesses some marvellous sights.

Last autumn, it was unspoiled views of the Northern Lights during a series of spectacular displays.

He sometimes spots humpback whales breaching.

And although Storm Babet and Storm Ciaran caused some damage to the jetty and adjacent road he was captivated by their full force, with waves over 40ft high.

David said: “You just sit back and admire it. It was epic to watch.”

David Steel says storms bring ‘siege’ mentality to Isle of May

He and fellow residents were cut off from the mainland for two weeks by the storms, with boats unable to reach them with supplies.

But being accustomed to island life meant David was prepared.

“Come September, you go into siege mentality and we know we have to get x amount of stock in just in case.

“Although we have a good water supply, if the system suddenly fails we have bottled water as a back up.”

David has become a self-confessed jack-of-all-trades fixing everything from electrics to blocked toilets. “I’m not going to get a plumber coming straight out here!”, he said.

Although he may be the sole human on the island in the first and last few days of each season, that doesn’t last long.

What do scientists study on the Isle of May?

Assistant Thomas Skinner quickly joins him before people from various universities and research institutes come for weeks at a time to study the birds, seals and even the mice.

“Everything on the island is studied,” said David. “The only thing which isn’t are the rabbits. We just leave them to it!”

Living quarters – known as Fluke Street – aren’t as basic as they would have been for the lighthouse keepers and their families who stayed there until 1972.

Today they are equipped with such luxuries as WiFi, power showers and soon Starlink satellite internet connection.

There’s already a communal area but David is also building a bar.

And he’s excited to show off his new television. Before smart TVs non-existent aerial reception made tuning in impossible.

But he admitted: “I don’t miss it, not when you’ve got this [indicating the surrounding land and seascape].”

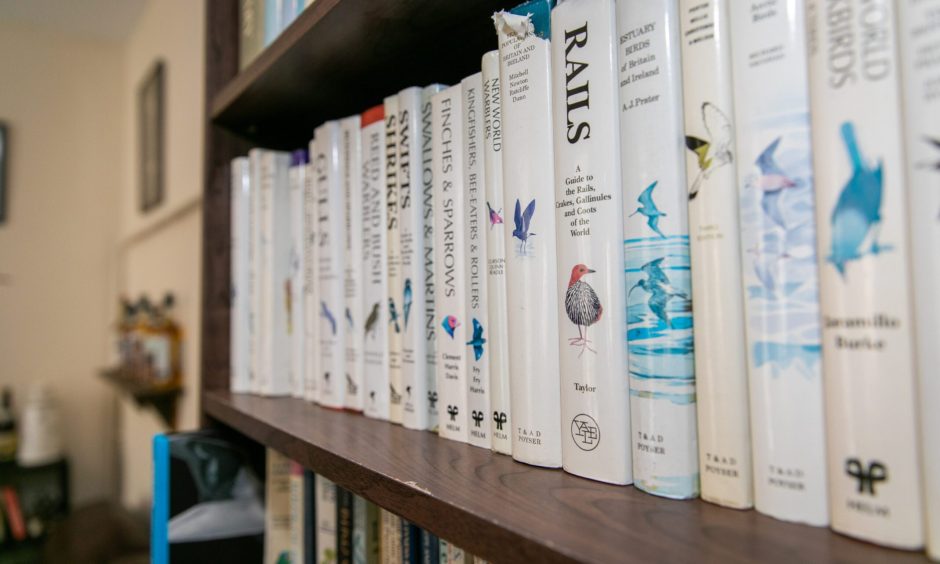

There are plenty of books to read too, but unless you’re a bird fan (and why else would you be here?) there’s not a great choice!

Long working hours during the summer months mean there’s little time for relaxing, though.

And for David work will soon include the painstaking puffin census when every burrow on the island – which is just under a mile long – is checked for occupants.

Bird flu hits puffin populations

Although puffin numbers have suffered from bird flu and climate change he expects to find between 35,000 and 40,000 breeding pairs.

He said: “It’s a bit like a police search. We go backwards and forwards across the entire island counting and checking. We walk every inch of the island. It’s a big job.”

Putting your hand down a puffin burrow is like a game of Russian roulette. You risk a nasty nip if you choose the egg chamber or a handful of something unpleasant in the waste chamber.

Drones and AI have made large gull counts easier, allowing the island’s cliffs to be photographed and the count by humans cross checked by computer.

The clown of the sea

Puffins are the island’s greatest attraction, and the number of visitors who sail to the island each season has increased from around 6,000 10 years ago to a record 16,000 last year.

With their distinctive features, the small seabirds are sometimes called the ‘clown of the sea’.

And they certainly create some entertaining moments for their human neighbours on the May.

When they leave the burrow, puffin chicks, known as pufflings, walk to the sea under cover of darkness.

David said: “In July if you sit out here at midnight you see this procession of chicks going down to the sea.

“But, of course they’ve never seen the outside world and we have to do rounds of the buildings because the chicks get stuck.”

A puffling in the shower

Lost chicks end up in all sorts of places.

“One of my volunteers was having a shower and she looked down and there was a puffin chick in with her.

“I had one in my kitchen. I was cooking and there was this chick happily watching me.”

It’s not just baby puffins that find their way into human quarters – David has also ejected a seal pup from his bathroom.

Ensuring the island is well stocked with food and other necessities is among David’s responsibilities. And being offshore doesn’t prevent him from ordering online like the rest of us, whether that’s Amazon or Tesco.

“We can get supermarket deliveries to the harbour in Anstruther,” he said. “They can bring it and put it on the boat.

Island shopping to Christmas shopping

“It’s bizarre when people ask where you want this delivered and you say to a harbour!”

Come November the other humans and day-trippers are a distant memory, leaving only David and Thomas behind for the final weeks.

Then, when the island’s buildings are locked up for the winter, another kind of shopping catapults the reserve manager back into his other life.

David said: “In the latter part of the season you’re used to being with just one or two people, then you go off onto the mainland and you’ve got to go Christmas shopping!

“It’s quite a culture shock to go back to mainstream life.”

Isle of May stints mean David Steel only sees his partner on the holidays

But it’s also time to return home to Northumberland and be reunited with partner Pippa.

While he’s on the island, he only sees Pippa during his holidays and for the odd long weekend, when either he goes south or she visits the island.

“She’s quite understanding about my job,” he said.

“We make the most of it when she comes on [the island] or we go off on holidays or weekends away.”

But he admitted he finds it harder to be away from her and his family the older he gets.

The day he drives north for the start of the season is one of mixed emotions.

“I’m pleased, I want to get back, but I know I’m going to miss Pippa.”

His job is one many people might do for a few years before moving into a role allowing a more regular lifestyle.

After three seasons on the Farne Islands a friend asked if it wasn’t time for him to leave that way of life behind for a “proper job”.

But he said: “That was 21 years ago. I’ll stop doing this job when I stop loving it.”

How to visit the Isle of May

The Isle of May national nature reserve opens to visitors from Monday until September 30.

Sailings can be booked from Anstruther, Dunbar and North Berwick.

From Anstruther harbour visitors can sail on either the May Princess ferry or the Osprey RIB open fast boats.

Conversation