It takes less than a darkening December hour on the freezing slopes of Ruthven farm to appreciate how exposed this Glenlivet unit is to the driving wind and snow.

At 1500ft there’s very little shelter from the elements, and 10 years ago there was considerably less.

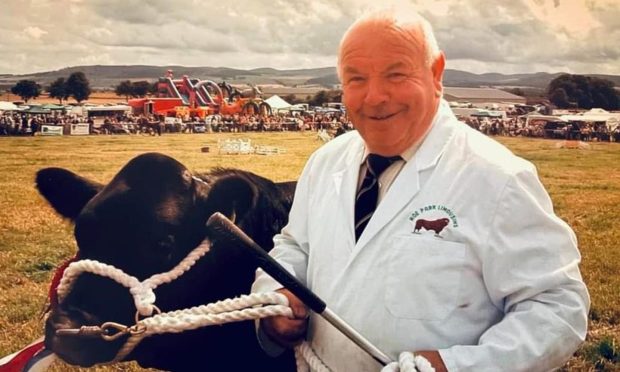

Jim Simmons has farmed here for 11 years and has just won a major plaudit for his dedication to the environment, but he readily admits that a decade of conservation work was kick-started by practical farming necessity.

His very first lambing of 800 Blackfaces hammered home just how bare the land was and how relentlessly the weather could dispatch a crop of new born lambs.

“We realised at once that the only solution was to plant trees – either woodland or hedgerows – to provide cover for the sheep,” he said.

“And as soon as we started we saw how it benefitted the stock and that fuelled our appetite to do more. But the bonus wasn’t just for the farm – the wildlife started to come in bigger numbers too.”

Jim and his wife Lesley have planted 38,000 trees, built three large ponds and sown wild seed mix for overwintering birds. They have fenced off land from rivers to prevent erosion which could damage freshwater pearl mussel beds, cut rushes to create feeding areas for snipe and sown species-rich grassland to attract butterflies and bumblebees. Grant aid has supported around 75% of their work and the rest is clearly a labour of love.

Yet while Jim clearly gets a buzz out of seeing how his effort has made the farm a haven for wildlife, he insists that farming always comes first.

“We mustn’t lose sight of what agriculture is about – it’s about food production. Everyone needs to eat, but there is plenty room to do everything else alongside that.

“We look at the poorer bits of land – the boggy or rough, unproductive areas – and know that ponds or scrapes or woodland won’t impact on the financial output of the farm. If adding these wildlife benefits is cost neutral and we’re losing nothing by doing it then we go ahead. It’s stewardship. It’s about striking a balance, looking after what you’ve got and making it better for the next generation.”

Jim Simmons is a successful producer of quality lamb and cattle, and Ruthven’s 800 acres of hill and improved ground mean it is a livestock farm through and through. The stock need to be hardy here, and in addition to the Blackface flock, there are tough Gascon cattle from the Pyrenees which out winter well.

However he is finely tuned to the messages coming from Brussels and Westminster that future farm support will demand a commitment to the environment as well as agriculture. He agrees with that policy but says that for conservation work to be , farmers have to be interested in the outcome.

He adds: “It’s all very well for the Government to give targets, but you have to want to do it. You need to want to look at the ways you do things and be prepared to consider how doing certain jobs differently might impact beneficially on the environment or the wildlife on the farm.”

As a relatively new farmer he says he probably thinks differently from producers who have been established for generations.

“Farming is a long-term strategy so change has to be gradual. I came in to the industry 11 years ago, at a point when things were changing and so was able to start from that place. We’re now adapting the business to new demands and also taking into account what the estate wants from the land.”

The Simmons are tenants of the Crown Estate Scotland which has been fully supportive of all the work he has undertaken on the farm. He has also had a sympathetic adviser who not only helped draw up schemes, but encouraged him to look at the work from a public perspective and be ambitious in the scale of his projects.

The most recent focus at Ruthven has been on creating the best environment for the oyster catchers, curlews, redshank, peewits and snipe which visit in summer and bring the upper slopes of the farm alive. He is so enthusiastic about the results that he plans to introduce farm tours next summer in order to share the experience with the public.

“We put in wader scrapes in unproductive wet areas,” he explained.

“They’re like mini ponds that gradually dry up and the waders feed at the edges. The birds found them within 48 hours of them being created – I didn’t expect that. We put in five but I wish we’d put in 20. Maybe I’ll put in more. There’s no reason why we shouldn’t.

“There were waders there before we started, but if you go up the hill on a June or July evening at around 8-9pm, the noise from the snipe is incredible.

“It’s what mosaic management is all about – providing shelter, cover and feeding areas. We feel we’re doing our bit by halting the decline of something that is already in trouble, and it’s not remotely detrimental to farming.”

nnicolson@thecourier.co.uk