Had Hamish Henderson been English and studied a culture in Borneo, say, he’d be famous and have a gallery in the British Museum.

He was Scottish, and studied Scotland, and that doesn’t count in the Anglo world.

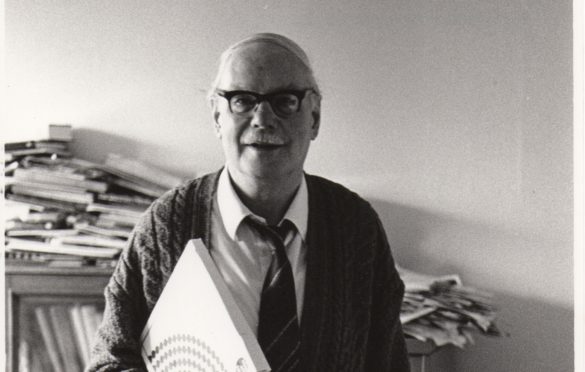

The 100th anniversary of his birth falls next Monday, and the nation should pause to honour the finest version of a Scot – a clever man dedicated to the people.

But enough of him, here’s a different voice. “There is a tradition of popular song in Scotland to which England offers no counterpart whatever, and a large part of the Scottish songs, alike in Scots and Gaelic, have always recognised economics and politics to be the substance of poetry – and who but prettifying cissies disagree?”

That’s the poet Hugh MacDiarmid, in his sleeve blurb for a record by Nigel Denver called Scottish Nationalist Songs, released in 1966.

He goes on: “War, wine and women” wrote a critic long ago “were said to be the subject of song, and England has not a dozen good songs on any of them.”

MacDiarmid’s rant concludes by saying the republican and socialist ideas in many of the songs went to show that the politics of “the great proletarian leader John Maclean” were the “way to go” for Scotland.

This is the voice of mid-20th Century politics, whether Scottish or anywhere else.

Revolutionary, radical and macho – “cissies”! And it may explain why Scottish culture is still seen as a half-formed thing by some.

The sense that it is political, drunken, masculine and aggressive. And that it is inexorably associated with anti-Englishness. Not a culture, but a grubby protest and therefore not as interesting as exotic tribes in Borneo or elsewhere.

Which is no justice to Henderson.

A night in Sandy Bells in Edinburgh with him in your ear would have been astonishing, like sharing a whisky with Jackson Pollock in lower Manhattan, or lucking out with a gimlet in Graham Greene’s company.

Overshadowed in the public eye by MacDiarmid’s strident poetry, Henderson has still to be accorded his due. He did more for Scotland than MacDiarmid ever did and can be said to have shaped modern concepts of our culture.

He founded the Scottish School at Edinburgh University, collected countless recordings of song and poetry across the land and, in being such a respected academic globally, asserted the internationalism of the democratic intellect.

We have heroes foisted on us and are slow to recognise the true greats. 19th Century Romanticism gave us the Wallace monument in Stirling, and old-fashioned elitism the grand column to Dundas in Edinburgh’s St Andrews Square.

In contrast, we didn’t get round to a statue for one of the world’s greatest physicists, James Clerk Maxwell, until a few years ago.

A bust of Henderson can be found in the newly-built business district of South Gyle in Edinburgh – it’s hard to imagine a more inappropriate spot.

The case needs to be made that Henderson is a truly great Scot, a father of the nation more important than any politician of the last 50 years.

Unlike MacDiarmid, he didn’t use his poetry or learning as bludgeon, but held to the ideas of international socialism sincerely and with humility.

What’s more, he spoke for the working man and woman everywhere, not just the Scot Nat.

He documented a culture that, while steeped in politics, was not a political invention, but as sincere a thing as any to be found across the world. What’s more he was a cissie – to use MacDiarmid’s bullying term – and advocated a tolerance and acceptance which we now find utterly normal, but was offensive to many in his lifetime.

He is best known for his song on international socialism, The Freedom Come-All-Ye.

Who knows all the words – I’d guess as many as can sing Scots Wha Hae properly, which is to say not many.

In both instances, that is a regret – Scots Wha Hae is Burns’ celebration of Thomas Muir, the socialist martyr.

The Freedom Come-All-Ye needs no disguise. It is a song for the people, an encouragement to come together regardless of race, class or religion.

For him, the socialism of John Maclean is not a weapon against the English, but a beacon to humanity.

When Maclean meets wi’s freens in Springburn

A’ the roses and geans will turn tae bloom

And a black boy frae yont Nyanga

Dings the fell gallows o’ the burghers doon.

In the week we celebrate the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, we are surely humming to Henderson’s tune.

That “burgher” Dundas, toady to the establishment and preserver of the slave trade, should be knocked from his column, and the prime spot in the nation’s capital be given to Henderson.

The centenary of the birth of Hamish Henderson is an opportunity for more people to recognise how he helped to shape Scottish culture.