It doesn’t look good for a political leader if their own future becomes the story during an election campaign.

This was the fate of Theresa May, who just survived in 2017 to endure two more years of unwanted career advice from colleagues and opponents alike.

Speculation in this election over her successor Boris Johnson’s tenure has faded as the Conservatives have held on to a steady poll lead.

But in the other parties, Jeremy Corbyn’s possible replacements are treating his departure as a given.

And Jo Swinson, only elected to lead the Lib Dems in the summer, was repeatedly asked by Andrew Neil if she would stand down after December 12, following her party’s collapse in popularity.

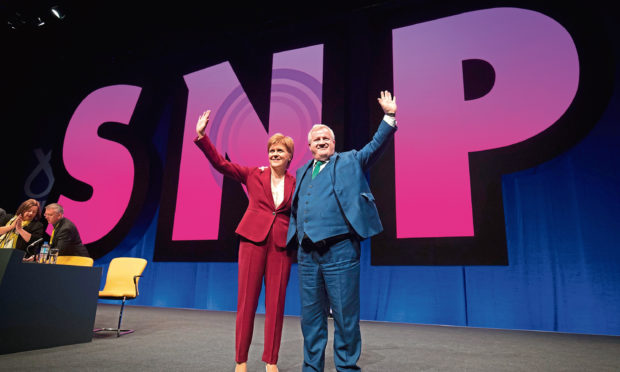

Of even greater interest in Scotland, though, is the question mark now hanging over Nicola Sturgeon’s exit date.

The SNP leader insisted in a newspaper interview on Sunday that she would stay put for another five years, but rumours that her days are numbered persist.

Much of the talk has centred on the likely fall-out from Alex Salmond’s trial in March on charges of sexual assault and attempted rape, which he denies.

Sturgeon will certainly be glad that ballot boxes open tomorrow instead of next spring, when the dust is still settling on the court case.

But, despite her protestations (what leader would make a pre-polling day resignation?), she may have other reasons to quit sooner rather than later.

However her party fares tomorrow, she has not made the case for independence, with the most recent polls showing support for a Yes vote has dropped below where it was in 2014.

This, and the realisation that she may be scaring marginal voters, forced her into a U-turn just days ago.

Having made the whole SNP campaign to date about Indyref2 and spelling out that a separation vote was her priority, she told BBC Radio Scotland on Monday that she now expected a new referendum on Brexit would take place first.

And, in her increasingly contorted logic, she argued that if the Leave outcome of 2016 was overturned, she would still have a mandate to re-run the vote on independence because of the “contemptuous” manner in which Scotland had been treated.

Clearly, panic has taken hold in the SNP high command and Sturgeon is trying to distance herself from her single issue agenda.

She told the Sunday Mail that she would best represent Remainers, even if they were Unionists or undecided on independence, because she would try to stop both Brexit and the Tories getting back into government.

“My message to them is that I don’t take their support for the SNP as necessarily support for independence,” she said.

She must be praying that the electorate has not been listening to her so far, since at every outing she has made it plain that success for the SNP on December 12 equates to a green light for independence.

In the past, Scottish voters have indeed been able to discern between a vote for an SNP candidate, Westminster or Holyrood, and a vote for breaking up Britain.

As support for secession stagnates, or declines, the Nationalists have still secured significantly more support than the other parties, although they lost 21 seats in 2017.

This time it is different, however. Whatever Sturgeon has said in the past few desperate days, voters must be in no doubt that backing the SNP will bring further division to this country.

If the Nationalists improve on their 2017 tally, even slightly, Sturgeon will hail the result as a stunning victory for her cause and her demand for powers for a new plebiscite will grow deafening.

But she can be stopped, and quite easily. Many seats hang in the balance, and can go to one of the Unionist parties on the smallest of swings.

Just two to three percent movement from the SNP to the Conservatives could see the Nats forfeiting four or five seats, according to the psephologist John Curtice. In Perth and North Perthshire, the SNP’s Pete Wishart won last time with a majority of 21, while Angela Crawley in Lanark and Hamilton East scraped in by 266 votes.

Labour and Lib Dem voters are being urged to knock out the Nationalists in some of these knife edge constituencies by voting Tory.

But elsewhere, it is the Lib Dems who could ruin Sturgeon’s night. For example, Stephen Gethins looks very vulnerable in north-east Fife, after winning in 2017 by two votes.

A bigger challenge, and a bigger scalp, is in Ross, Skye and Lochaber, where surely all eligible Unionists will be rooting for Craig Harrow in a bid to despatch the SNP’s Ian Blackford.

Scotland could end an era of bitter divide in these lands if only they would give Sturgeon a bloody nose and dash secessionist dreams for another generation.