Three things happened in 1957: Anthony Eden resigned, the European Union began, and Alec Guinness starred in a prophetic movie.

It was Eden’s disastrous bid to retake the Suez Canal that marked the real decline in Britain’s post-empire status.

The Treaty of Rome saw an alternative to the plucky nation in supranationalism – the cooperation of countries for a greater good. West Germany, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Luxembourg and Belgium came together as the founders of what’s become today’s EU.

Alec Guinness starred in two movies that summed Britain’s confused sense of itself.

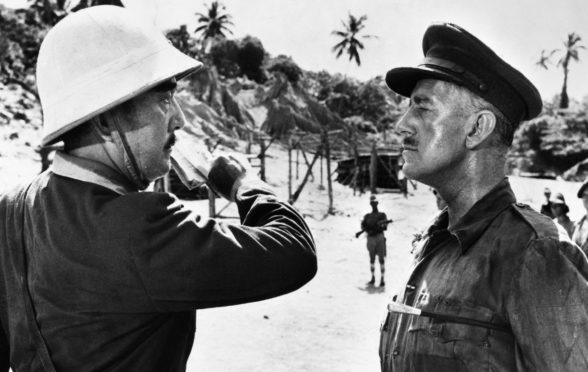

In The Bridge on the River Kwai, he represents the stiff upper lip going mad with rigidity. In the much less famous Barnacle Bill, he is a naval captain who suffers from sea sickness. Comically, he takes command of an amusement pier. It rots and the film ends on Guinness going down with his planks.

Brexit rests on a wobbly idea of English identity

And 63 years later, tomorrow, Britain will leave the EU. Apparently to wrest itself from the decline of Europe and to become a heroic nation again.

Brexit rests on a wobbly idea of English identity – Douglas Bader, tea during the Blitz and “our kind” running the country. The assumption is that Scotland looks stable in contrast.

Yet we come out of this shambles looking confused between nationalism and supranationalism. Perhaps also looking like a people who only want what the English don’t.

Through English post-war culture, two themes prevail: the sacrifice during the war, and the comic shambles to follow. Tales of heroism and defiant individualism abound at the movies.

At the same time, the war is cliff edge off which clowns fall. The loss of empire and the decline in international status is there in Barnacle Bill, as it is in a string of films, books and plays which depict an England losing its confidence and beginning to pick at its soul.

Our culture doesn’t revolve around hatred of the Germans or French, but a growing suspicion of the English.

This is not a British thing – though it was presented as such. The cultural significance of the war as a national high point, and the decades that followed as a low, are treated differently in Scotland.

Scots looked inward. Our story became one of disappointment. An economy heavily dependent on manufacturing grew weak with global competition. We didn’t seem in control of our fate, so turned to nationalism as a vehicle towards internationalism.

For Scots, the war isn’t a “national” thing, but a misery to be put behind us. Our culture doesn’t revolve around hatred of the Germans or French, but a growing suspicion of the English. Our conclusion is that the nation (read England) doesn’t need to be liberated from the continent, but the nation (Scotland) isn’t happy where it is.

Yet Brexit shows this to be weak. Scots voted to stay in the EU. The denial/resistance of this has become the notional stone of argumentative destiny. Which is all good fun – but it takes Remain Scots to a very different sense of nationalism than Leave Englanders. Where England gets its Barnacle Bill on the pier, we get the madness of rules.

Rejoining the EU?

Scottish nationalism is heavily invested in rejoining the EU. Only that’s far more tricky than it appears.

Say there is another vote on Indy in 2022, which seems the earliest credible date. If yes wins, that would lead to three years of negotiations with the UK. Which would mean Scotland wouldn’t be an internationally recognised state until 2025.

At that point, it could reapply for EU membership. There would then be complex negotiations about Scotland/north of Ireland/Ireland, let alone intricate legal arrangements about the Scotland/England border. And there is the matter of currency. It is fanciful to think Scotland could invent her own one when also joining the Euro bloc.

Joining the EU takes time, even as a favoured state. A few years in the queue would be standard. Which means Scotland is close to a decade away from being back in the gang.

English nationalism… Scottish nationalism… The future of both looks uncertain

If it fails, or chooses not to rejoin, would that invalidate the promises of independence?

English nationalism will have its day tomorrow. Scottish nationalism is still a failed project – so far, it only exists as the driving force for devolution. The future of both looks uncertain.

The English nation invoked today was being lampooned 70 years ago. By the English. It would be astonishing if it was real now.

But it’s no more optimistic for Scotland. Our nationalism has become so bound up in not being Tory and on bureaucratic matters, it has little sense of its own purpose.

What is our destiny beyond the rules of treaties and unions?

That Scots want, and deserve, to be heard is valid. Same goes for English leavers. Both have a sense of democratic justice. It’s just not clear if they are in command or are falling off a pier, like Barnacle Bill, slipping into the sea while staying with his ship.