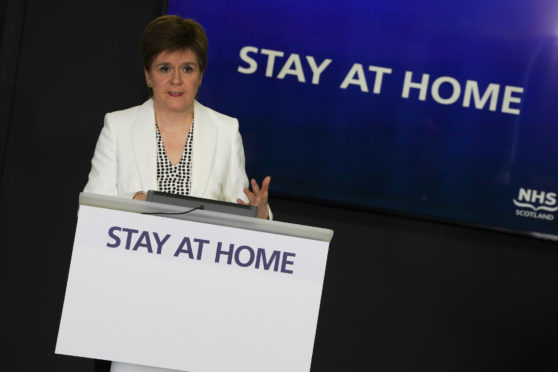

Scotland is at last to have its own route map out of the coronavirus lockdown, Nicola Sturgeon promised on Monday.

We still have to wait until May 28 at the earliest for the same freedoms currently being enjoyed south of the border, such as visiting golf courses, recycling centres and gardening shops.

But even the First Minister conceded, though not in so many words, that Boris Johnson was right after all, and Scotland also ‘needs to get some normality back’.

The question is, now that she has accepted the inevitable, why are we being made to wait at least two weeks longer than England, Northern Ireland and Wales for what will likely be fewer concessions?

Vague talk about ‘R’ numbers – Sturgeon’s main justification for diverging from a UK wide approach – doesn’t add up when there are regional variations in the spread of transmission within Scotland.

If she followed her own logic, she could have already released the Western Isles, where there have been no Covid deaths, and the Northern Isles, with a combined total of under 10 fatalities according to the latest figures.

While the Westminster government pleads with teaching unions to get children back to school in June, Scotland seems to be kicking that particular problem into the long grass.

Summer holidays do start sooner here than in England but that is no excuse to drag out the damage being done, especially to the most disadvantage pupils, by months of educational neglect.

There is no evidence from those countries that have reopened classrooms that teachers are any more susceptible to catching the virus than, say, supermarket workers, and their jobs are surely just as key.

The children themselves, as we have known all along, are mercifully unaffected by the symptoms of this disease.

Even less clear is why businesses have not been given a timetable for reopening, as they have in England, and why major chunks of the economy cannot crank up straight away – for instance, the construction industry.

Guidelines to builders north and south of the border have differed from the start, with Scotland insisting sites must close unless they involved essential infrastructure, while the UK government advised that work could continue so long as social distancing was in place.

The SNP decided for reasons unknown that the building of houses was unsafe here, though companies such as Persimmon picked up tools elsewhere in the UK after installing protective measures.

As of last week, the picture became even more confused, with all construction workers in England expected to come out of furlough while Scotland remained at a standstill.

The construction industry, with its high levels of self-employment, sole traders and narrow margins, has been badly hit by the lockdown.

One builder, whose furloughed staff are moonlighting as delivery drivers, worries that he won’t have a business to tempt them back to.

The continuing delays will hurt not just private contractors but local authorities and the bigger public sector projects – which is perhaps why builders at sites in Glasgow and Motherwell were reportedly back at work this week.

Among the most inexplicable cancellations is the dualling of the A9, Scotland’s longest and most dangerous road.

Machinery has lain idle and workers have been paid, by the UK Treasury, to sit at home (not their fault) when at almost no risk they could have made significant progress in upgrading this route and making it safer.

The Scottish Nationalists taking these decisions must be secretly grateful they have the broad shoulders of Great Britain to lean on in their time of need. There is no way that Scotland itself could cushion its workforce.

For Sturgeon, now she has survived a few difficult days’ scrutiny over Scotland’s mishandling of the care homes crisis and an apparent Covid cover-up at a conference in Edinburgh, lockdown limbo is a win win.

A split with London, however manufactured, is always preferable to toeing the Tory line of Number 10.

And thanks to the extraordinary circumstances, no one is sufficiently well versed in the science to challenge her health advisor, Jason Leitch, every time he gratuitously makes a special case out of Scotland.

But mostly, the prolonged imprisonment of the public serves another purpose for the SNP leader. Once this is all over, and people start to pick up the pieces of their old lives, the old politics will also resume.

The thought of this may be behind the reluctance of many Scots to emerge from hibernation. The pandemic has becalmed the nation to some extent, but not its top separatist echelons.

Sturgeon knows that as soon as she has fought off the virus, she will have to face the more ferocious enemies in her own party, which is now split into two bitter camps. The past months will seem like a doddle.