Although there will no doubt be much fanfare surrounding the launch of the SNP’s manifesto today, it hardly matters what it contains.

Those voters who are in favour of independence will not be too bothered by the nationalists’ plans for raising taxation or their lack of ideas on education reform or improving health care.

They probably won’t even bat an eyelid over the news that every family will receive a “baby pack”, the latest in a long line of pre-election pledges that sound catchy but do little to address this country’s real problems.

The SNP can, and in fact has, made a hash of most spheres of domestic policy but so long as they remain committed to breaking up Britain, a significant section of the population will continue to vote for them.

The old notion that people, however politically tribal, would weigh up one party’s pledges against another’s and mark their ballot papers accordingly no longer computes in Scotland, where the electorate is largely split along the lines marked out during the 2014 referendum.

This will ensure the success of the SNP on May 5, and the only real fight left is between the unionist parties for second place.

All the nationalists have to do now is keep the independence dream alive for their faithful followers, however distant that dream grows.

Another referendum

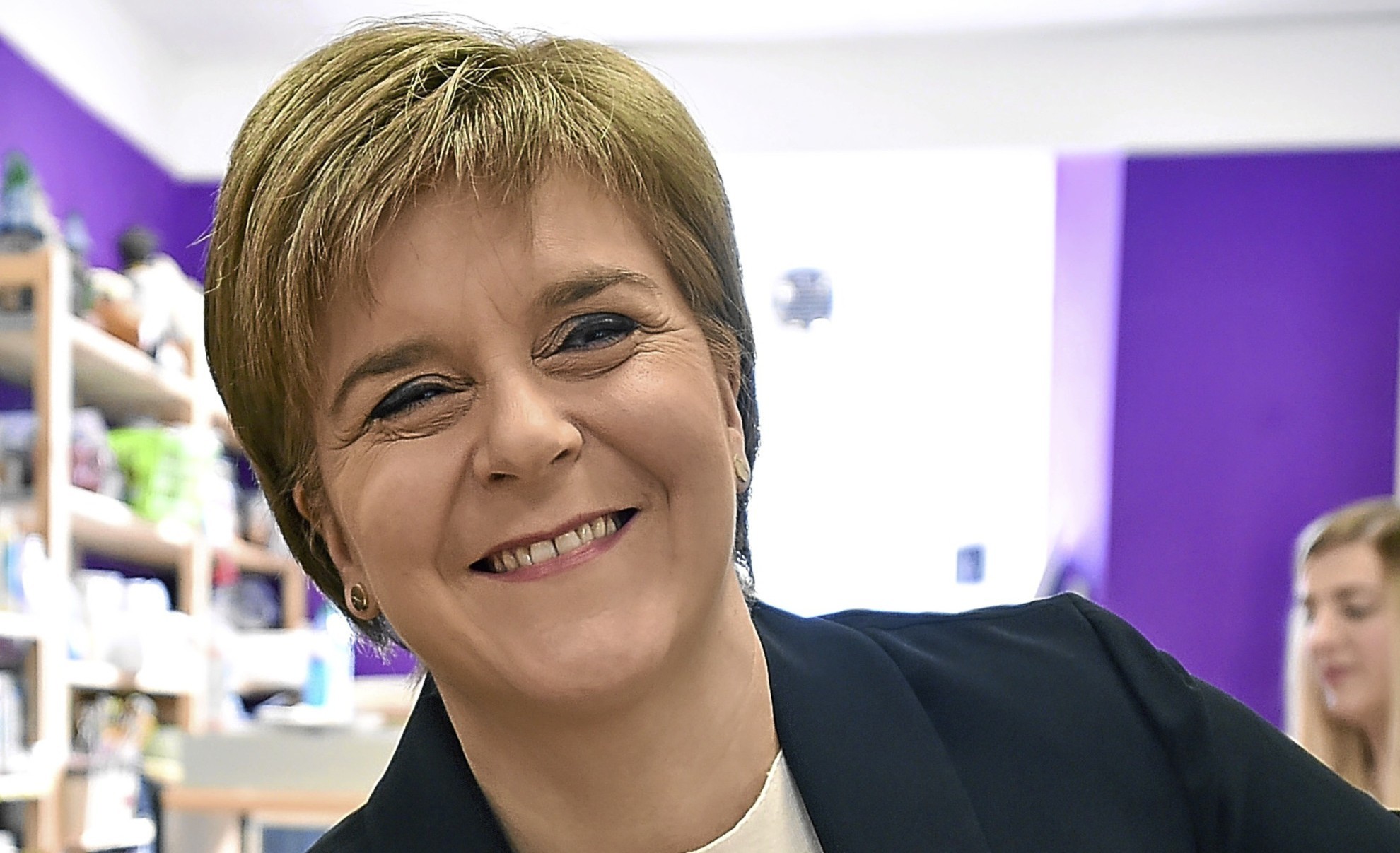

So, today Nicola Sturgeon will set out her current position on separation by saying the Scottish Parliament should have the right to hold another referendum “if there is clear and sustained evidence that independence has become the preferred option of a majority of the Scottish people – or if there is a significant and material change in the circumstances that prevailed in 2014, such as Scotland being taken out of the EU against our will”.

She has been saying this for a while and it falls well short of including an option for a second referendum in the manifesto.

But it is still cause for dismay among those of us, the majority remember, who would dearly love Scotland to move on.

Sturgeon knows her party doesn’t have the numbers to win a repeat vote on the constitution so soon after losing the last one, and has made no discernible headway on this issue in 18 months.

Even if the rest of the UK voted to leave the EU in June, there is no evidence to suggest that pro-union Scots would convert to nationalism.

She and her more experienced ministers, wedded though they are to the secessionist cause, must also realise that current domestic crises will not vanish whether Scotland is independent or not.

But she is dealing in her party members’ expectations which, thanks to the extravagant claims made by nationalists during the Yes campaign, can only ever be fulfilled by a fantastical separatist utopia.

Once re-elected, as the nationalists surely will be, Sturgeon will probably have a comfortable enough majority to do what she likes.

She will have at her disposal the most extensive powers of any devolved administration. She could do much to improve public services, if only she concentrated on what is good for Scotland rather than what is good for her and her party.

Impossible promises

Nothing could be further from her mind, I fear. Instead of running the country she is determined to be distracted by constitutional promises she can’t keep.

“In the next parliament, we will work hard to persuade a majority of the Scottish people that being an independent country is the best option for our country,” she said over the weekend.

Valuable ministerial time and departmental resources will be diverted away from a health service straining to provide basic care, and from schools that are crumbling, literally in Scotland’s capital city where 17 buildings have been closed indefinitely.

As the nationalists won’t change their priorities, we must pray that the electorate will or we will be doomed to refight the referendum at every election for the foreseeable future.

This may be clutching at straws but there have been signs recently that people are beginning to question SNP dictates.

In one area, in particular, the party is failing to convince even its own supporters that it always knows best.

Its Named Person scheme – government control gone mad – has caused much consternation and a survey on Sunday revealed 59% were opposed to it. Another reason for hope is the coalescing of opposition to the nationalists around an apparently resurgent Scottish Conservative Party, creeping ahead of Labour as the most convincing of the Unionist parties.

Is it possible, after the years of SNP domination at Holyrood, that a viable alternative is shaping up on the other side of the political spectrum and that Scotland will return to being a two party, if not a three party, state? For all our sakes, let’s hope so.