The SNP are like the political wing of the Rotary Club. There is something irrefutably nice and well-meaning about them. The SNP manifesto is out and it’s their best – detailed, considered and focused on important issues.

To pledge that providing childcare is the “most important infrastructure project” is serious stuff. How we fail our new born is how we fail our nation – if this is to be corrected, then the coming government could be great.

Pledging money to close the attainment gap between rich kids and poor ones is entirely commendable, and the commitment to honour all the recommendations of the Poverty Adviser proper politics.

As a former SNP policy chief, I have the pleasant experience of seeing the party get serious in a way that I failed to achieve.

Like a charitable body of well-meaning people, the logic behind their actions is often confused. On the one hand they pledge to “do everything” to resist austerity, but not actually raising taxes or removing middle-class perks.

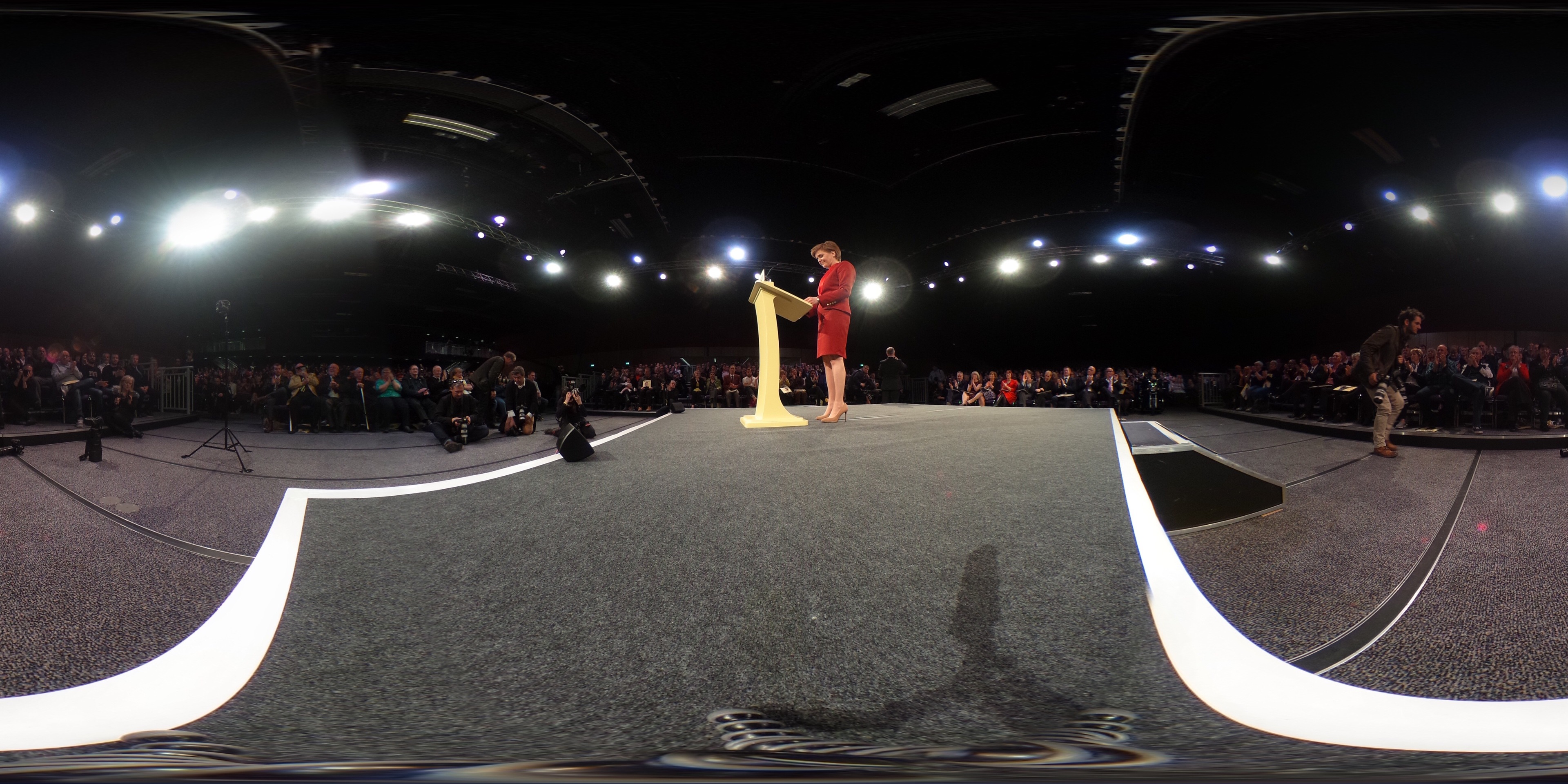

Why? Because they won’t be beholden to raising tax just to meet a shortfall from London, Nicola Sturgeon told the manifesto launch. Doesn’t resisting austerity mean resisting Tory decisions? Not when it might scare off middle class voters.

Cop out

The SNP are spending £750 million on closing the attainment gap, an extra £500m for the NHS and god knows how much on the early years commitment – which doesn’t sound like austerity in the first place.

But it’s rude to quibble in the face of nice people trying their best.

They accuse other parties of copping out by only aiming for second place, and then deliver the greatest cop out in Scottish political history.

Independence is no longer an actual policy – instead it is a thing about which the SNP will try to persuade people and if they fail, then so be it.

Even this isn’t really a problem – the SNP more than any other party have recognised that the age of big change and competing ideas is over.

Scotland isn’t going to vote for independence because it is a financial puzzle even the SNP can’t solve. Why let that interrupt the joys of office and the good intention to govern well?

As such, the party has tapped into the reality of Scotland brilliantly.

We are not the place of popular myth – of radical ideas and vigorous arguments. We are instead a pretty middle-of-the-road nation, broadly content with its lot, pleased to have asserted its identity, and content to be governing with what powers have been won.

In truth, we should all be grateful for this.

Changes

Nicola Sturgeon has been a member of the SNP for 30 years. Back then, in 1986, the idea that Scotland would be devolved was remote.

Had you then said that the main parties would be led by women, people would have laughed.

That two of those women are openly gay would have seemed as likely as a Rangers/Celtic merger.

And all this is very good. Scotland in 1986 wasn’t a nice place. It was angry, macho, sexist and riven with sectarianism. Of the last, the matter isn’t history, but is a lot less aggressive in people’s lives.

Now we conduct an election on our own terms, with political leaders who are pleasant, polite and thoughtful.

This is a land transformed. It’s duller for it – our politics has no ideological divide, no towering intellects or great speakers.

The great upset of Thatcherism, then devolution and the referendum have shaped a new place, but the upset is over.

Myth gone

The old myth of Red Scotland may no longer stand, but Scotland clearly stands as a place which is different. Not just in the UK, but across Europe. We have a strong nationalist party and government, but no resurgent right wing.

We talk about austerity, yet seem to manage pretty well when it comes to finding money for new wheezes.

The SNP, along with other parties, are methodically getting around to the big issues of making our society fairer, of spending money on children.

When answering questions from the media, Nicola Sturgeon admitted a significant truth.

This happiness has been achieved by people changing their minds, and none more so than the SNP.

She said her next government would be about “doing things that we didn’t previously think we’d do”.

Back in 1986, Nicola and the rest of the SNP would have been up in arms at the idea of money going to school heads and bypassing local authorities.

When Tories suggested just such a thing, they were condemned for not understanding Scotland.

Now it’s SNP policy.

There lies the secret of nationalist success, and the proof that we are a thoroughly changed place.

Policy now springs from need, not the need to whip up a rammy. And under the banner of “Scotland’s Party” you can pick and mix policy as you like.

Sure, there is a lot more to do, but I feel privileged to have lived through those 30 years, to have seen the change, to see what Scotland has become.

I miss the rammies though.