Unpalatable as it may be to people like me who voted Yes in 2014 and will vote Remain in 2016, the issues which drove up the indy vote will also propel the Brexit one.

Both referenda pitch the status quo versus a challenger. Both rest on the idea that the existing system is so broken it must be abandoned, not reformed.

This is difficult for pro-EU Scottish nationalists who have spent years distancing themselves from the tone of Farage’s British nationalism.

No matter, anyone interested in the idea of Scottish independence must face up to the realities of what the EU debate tells us about modern politics and single issue votes.

The SNP’s and the wider Yes movement’s pro-Europeanism seems sensible to me.

The message is Scots can choose their unions – that the EU may be a better partner than the UK.

This is consistent with Scotland’s unique brand of soft nationalism.

It rejects the hard nationalism or race, blood and borders.

This soft version has allowed Scottish nationalism to accommodate all the modern anger with old-style politics – Yes embraces people who don’t trust the elite, who reject old assumptions, who want a ‘better’ way.

So does Brexit, to a degree, alongside the same faith in national sovereignty over existing compromises.

Brexiteers want to assert the nation of Britain, fearing its identity has been lost in the pooled sovereignty of the European Union.

The SNPs want to assert Scottish identity over the pooled sovereignty of the UK.

“It’s not Britain leaving the European Union, it’s Britain joining the rest of the world” is how Liam Fox put it – a remarkably similar proposition to Winnie Ewings’ “stop the world, Scotland wants to get on” from the 1960’s.

Anti-EU people claim money is being sent to Brussels which could be better spent in the UK.

Yes asserted money was wasted on a corrupt Westminster which could have been spent on a better society at home.

Brexiteers say money which is wasted could go on the NHS – a direct echo of the SNP campaign’s ‘bairns not bombs’.

Vote Leave say they are challenging the elite – search the literature of the SNP from 2012-2014 and you’ll find the word ‘elite’ crops up a lot.

Salmond omitted criticism of Tory Toffs from a speech in 2011, but it became acceptable from 2012 onwards.

In 2016 it appears in this form – “(there is) a divide between big business, big politics, wealth, influence and everybody else in this nation – these are the battle lines in this referendum. It is the people versus the political elite”. That’s Nigel Farage speaking to the BBC.

Brexiteers say they represent people who want a new politics – a clear echo from the 2014 campaign.

“There’s an increasing gap between the governing and the governed” is how Liam Fox puts it.

It reminds us that within a single issue vote, all manner of opinions are contained, and any number of strategies can develop but crucially, the challengers to the status quo can build momentum on the idea of change.

The problem is untangling all this during and after the vote.

We still don’t know how the Yes vote divides between hard nationalist, soft nationalist, disgruntled labour voters, disaffected non-voters, anti-trident campaigners and people who felt an astonishing opportunity had come along and it was important to be positive.

A referendum is a blunt tool which gives the appearance of choice, while confusing a thousand different motives.

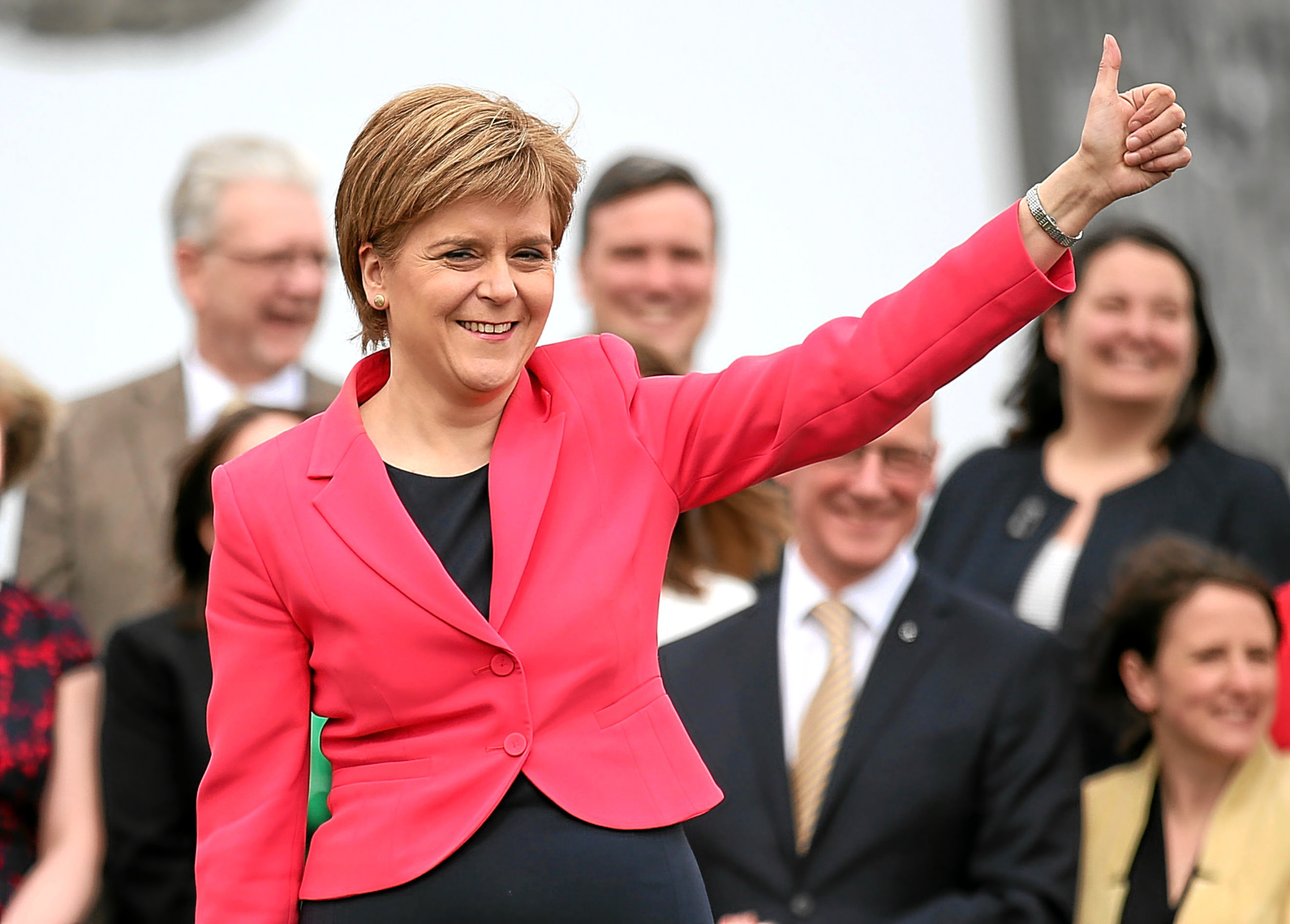

I fear slightly for Nicola Sturgeon tomorrow night in a TV debate – she has honed the slightly punchy debating style of Salmond with pleasant streaks of humour and self-awareness.

It’s not her debating style that will let her down, but her message.

We may be very familiar with the nuances of our soft nationalism, but are waivering English voters?

When she speaks in favour of pooling sovereignty, won’t the Brexit camp point out she no longer wants to pool with London?

When she defends cooperation will Boris Johnson not say she spent a career trying to end cooperation with England?

When Nicola tells UK voters that it is just not true that the UK sends £50 million pounds a day to Europe, won’t Boris mock her for a poor record on economic detail.

The 2014 referendum showed that many in the UK had only the faintest grasp of Scotland’s nuanced arguments. To imagine that, two years later, these same people are at ease with the Scottish argument and the complexities of the EU debate is wishful at best.

I remain unconvinced that the people of England want a Scottish Nationalist to tell them how to vote – here’s hoping I’m wrong, as the Brexit campaign approaches the big vote with all the confidence of Yes in the first weeks of September 2014.

And here’s hoping that the enthusiasm of the outsiders and the excitement of challenging the status quo isn’t enough to push Brexit over the line.

If it does win – and this is quite possible – then it will be the same forces of dissatisfaction and idealism which boosted Yes – how ironic, how horrible.