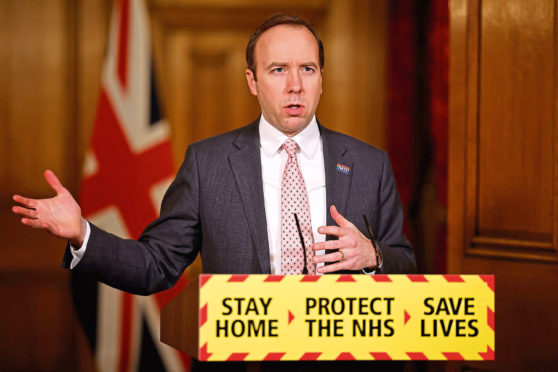

The mood of Health Secretary Matt Hancock was almost celebratory on Monday evening as he reeled off the numbers of people vaccinated against coronavirus and the high take up percentages among the elderly and vulnerable.

The roll-out programme, that has been almost world beating in England, is set to reach a major milestone next week when all the over-70s should have been offered the jab.

So confident was Hancock of beating the target – reaching 16 not 15 million by February 15 – that he urged everyone in the 70-plus age group to now contact the NHS if they had not already received their injections.

In Scotland, people over 70 must continue to wait for the NHS to get in touch but even here the slow rate of inoculations has been stepped up in the past week.

Along with the progress in vaccinations, there has been a marked decline in Covid transmissions across the UK, and a drop in hospitalisations, ICU admissions and deaths.

The R number is below one in most parts of the country and lower in chunks of Scotland than in the good old Tier 2 days of early autumn.

For the first time since the new variant entrapped us in the current lockdown, there is a sense of a corner being turned in controlling the disease’s spread.

Even the panic around the South African variant has been nipped in the bud, with reassurances from ministers and health experts that the Oxford AstraZeneca does protect against serious illness and death.

We should, therefore, be feeling as cheerful as Hancock but we have not yet been given permission to rejoice. While the facts point to a pandemic in retreat, the narrative around lockdown remains unchanged.

Boris Johnson is set to announce his roadmap out of the restrictions on February 22, but this week he would not rule out extending the curbs.

And though Nicola Sturgeon said last week that she was ‘cautiously optimistic’ about a gradual easing around March, she remains focused instead on an unworkable quarantine plan.

On both sides of the border, the original purpose of lockdown, to relieve pressure on hospitals and stop people dying, has been traded up to eradicating all Covid related risk.

But once the more than 90 per cent of the population who are most likely to die of the virus are no longer in danger – a goal now in sight – there is no reason for the rest of us to remain under house arrest.

Governments and their advisors have done a brilliant job in terrifying the public, with the result that many otherwise rational people, and not just the physically fragile, are resigned to their imprisonment.

There is a difference between stoic compliance in the face of a real threat and supine capitulation once that threat has gone.

Despite its grim toll, for the vast majority of us, Covid is not a killer. Whether we believe in the effectiveness of blanket shutdowns or not, we have done what we were told to do and mostly emerged unscathed, but not unaltered.

Rage against the confiscation of our liberties seems to have been replaced by complacent boredom, a worrying sign that we are adapting to the prolonged state controls.

We need to be constantly reminded of the collateral damage of lockdowns – the lost generations of children deprived of education, the greater price paid by the poor, the businesses destroyed, and the other health problems neglected.

A former nurse from Glasgow, whose breast cancer has spread to her brain after her treatment was delayed for seven months, spelt it out: “Cancer didn’t go away just as Covid hit.

“This has been a direct impact of decisions made by politicians and people with no clinical expertise. Doctors’ hands were tied,” she told a newspaper this week. “They talk about ‘protect the NHS’, but in this instance the NHS was not protecting me.”

There will be thousands more stories like this. And we have not begun to measure the harm on the nation’s mental health, and in particular on the young, who have struggled far more than the middle aged Covid consensus comprehends.

There are, mercifully, pillars of the pandemic establishment who now appreciate that we have to learn to live with this virus, much as we learnt to live with HIV.

Their wisdom must prevail. We need an exit strategy that overturns the thinking of the past year; that acknowledges the mistakes made; trusts the vaccinologists to keep future outbreaks at bay; and restores the principle of individual responsibility on which our democratic society is based.

What we most definitely don’t need are more dire warnings cancelling summer; the cruel separation of old folk from their families; and the fiction that this is the new normal. It is not.