The Scottish election campaign was barely two days old when it descended into a slanging match between the rival nationalist factions.

Since Friday, when Alex Salmond launched his Alba party as a ploy to hoover up seats via the Holyrood list system, we have been treated to a spectacle of Nat-on-Nat bile.

In scenes that make even the Salmond parliamentary inquiry seem sedate, the current and former first ministers of Scotland, supported by their camps, have escalated their mutual animosity to cartoonish levels.

If Salmond did end up holding the balance of power in a hung parliament – one possible outcome of his Alba strategy – there is no way that his passive aggression and her blatant aggression would ever coalesce to create political harmony.

So, it beggars belief that anyone but the diehards is still thinking of voting for either the SNP or the rump of its defectors.

The prospect of a parliament dominated by the same separatist squabbles that have embarrassed Scotland for months should surely deter most swing voters.

On the domestic front, Sturgeon can only offer bribes, given her party’s dismal record over the past decade and more.

She has vowed to tackle child poverty after making no progress in 14 years; and she has recycled an old commitment to increase cancer screenings, despite failing to deliver on her promise of establishing early diagnostic centres by this spring.

And, trying to maintain an honest face, she told schoolchildren they will all have access to digital technology, when thousands of them, particularly the poorest, were crying out for such help at the start of the lockdown last year.

As the former leader of Scottish Labour, Jim Murphy, tweeted: ‘It takes a special brand of duplicitous cynicism to know that you could have given a laptop to every single pupil in Scotland during the pandemic, but hold off doing so just so that you can announce it as an election pledge.’

It takes a special brand of duplicitous cynicism to know that you could have given a laptop to every single pupil in Scotland during the pandemic, but hold off doing so just so that you can announce it as an election pledge. https://t.co/fXYUCzdvFE

— Jim Murphy (@glasgowmurphy) March 28, 2021

But, as Sturgeon made clear in her opening election gambit on Monday, it will be independence that is at the heart of the May 6 ballot. Nationalist failures on matters such as health and education will not worry the core Yes constituency.

That may have been the case in all recent Scottish elections but now there is a last gasp desperation among nationalists, before they tear each other apart, that has catapulted the constitutional question to the fore.

And if Salmond’s renegades add to the pro-independence tally of MSPs, as he predicts, rather than spilt the nationalist vote, Scotland may be bounced into a second referendum that few Scots regard as a priority.

The unionist parties, therefore, have to fight this election more like the 2014 referendum than an ordinary battle.

Together, they command a greater percentage of the electorate than the nationalists and represent majority opinion on breaking up Britain.

On top of this, they have a very good case post pandemic, and could argue that Scotland would miss the £13.3 billion in UK Treasury Covid impact spending without the Union, not to mention the billions in furlough money that has kept food on the table, and the UK’s triumphant vaccination programme that has kept people alive.

Mass tactical voting could see off the nationalist threat if, say, Labour candidates in Tory strongholds stood aside and vice versa, with the Lib Dems also playing the game.

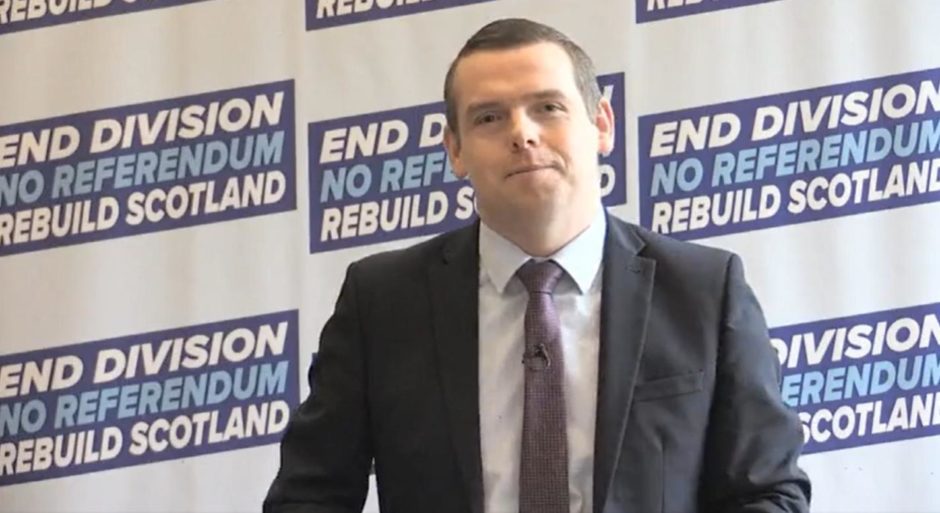

The Scottish Conservative leader, Douglas Ross, has offered to broker such deals but was unceremoniously rejected by both the new Scottish Labour leader, Anas Sarwar, and the Scottish Liberal Democrats’ Willie Rennie.

This is completely predictable, especially with Ross claiming – legitimately but condescendingly – the upper hand as Scotland’s second biggest party.

But this knockback is hopefully just the first round; all unionist parties need to have another go at getting on. There is too much at stake to risk the loss of treasures such as Labour’s Jackie Baillie in marginal Dumbarton, and much to be gained, in potential nationalist scalps, by a joint effort.

For the Ross plan to succeed, Ross, who has agreed to stand down some of his own contenders in hard-to-win seats, must himself take a step back.

Better Together saved the Union seven years ago because parties were able to unite under the relatively non-confrontational leadership of trusted Westminster Labour veteran Alastair Darling.

Today, an experienced parliamentarian respected on all sides could assume a similar role: the Lib Dems’ Orkney MP, Alistair Carmichael, is already chairman of the Scottish party’s campaign and might be able to build political bridges that are out of the Tories’ reach.

It’s worth a try. An alliance of unionists would not only maximise the pro-UK vote, but through their cordial cooperation they would help restore Scotland’s reputation following the nationalist hate fest. The nice parties versus the nasty parties; it’s no contest.