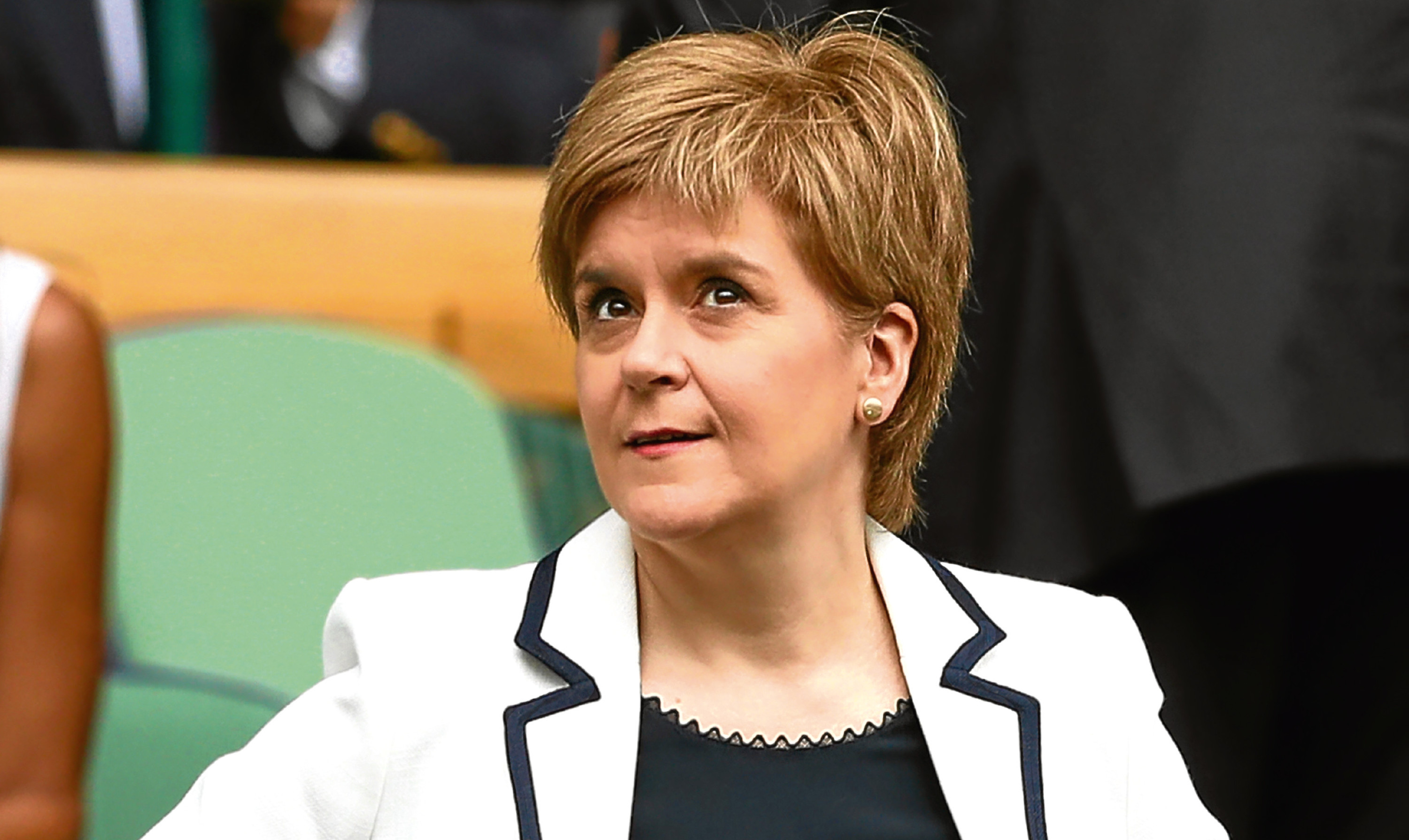

Theresa May and Nicola Sturgeon appear as chalk and cheese but it is the similarities which are striking.

With the SNP MPs sitting down during the standing ovation to David Cameron after his last bout of Prime Minister’s questions, we are invited to think there’s nothing alike about these tribes.

Scotland radical, progressive and lefty – and definitely not Tory.

Nicola the social champion, the fighter for equality.

England – reactionary, perhaps racist and firmly to the right.

Theresa the voice of the establishment, the conservative and reactionary.

All drivel, of course.

The two women may have grown up in wildly different political traditions but have arrived at a similar places, both in terms of career and philosophy.

Sturgeon reinvented the party after the loss of 2003, discovering a winning way for a movement that looked out of ideas.

May challenged her colleagues with the “nasty party” jibe, as much part of the refashioning of the Conservatives as Cameron’s “hug a hoodie”.

Holding their own

Both have risen in largely boys’ clubs and held their own in the company of bantering lads.

Both have mastered complicated departments and got out with reputations intact.

As to radicalism, May comes out on top. In her six years at the Home Office she reformed the police, even daring to suggest they might be bent.

Her brave challenge of the boys in blue is the kind of gutsy thing few politicians do and has no equivalent in contemporary Scotland.

Theresa’s leadership bid speech is a canter through progressive ideas – championing equality, putting workers on the boards of blue chip companies and reforming the economy so as not to leave the poor behind.

It could have come from the mouth of Nicola, who also stamped genuine policy reform on her leadership.

Top of the new Prime Minister’s agenda appears to be continuing David Cameron’s effort to substantially improve life chances – which means more attention to early years and tackling economic discrimination.

What’s not to like?

The SNP won the recent Holyrood election on the fine words of making childcare “the biggest infrastructure project of the government”.

We must all hope this is delivered but now we can compare our success against the same policy ambition down south.

Sturgeon’s other big idea was lifted straight from the Tories – empowering head teachers to manage schools, cutting through curriculum waffle to core teaching and testing pupils.

There’s no reason why Scottish policy should differ from English policy but nobody predicted that is how devolution would evolve.

Two women leaders, both interested in the same policy, both equipped with the humourless determination which gets things done, if winning few friends.

Surprisingly, it is May who has the clearer mandate – Brexit and be done with it.

Sturgeon still struggles with leading a massively successful party which struggles with its purpose – is it independence, is it within the EU, is it all just a pose to get the most out of the UK?

Strangely, both women came to the high office because the former leader had to resign within hours of losing a referendum. Salmond and Cameron’s departures put their legacies in to a stark light.

Sturgeon’s predecessor achieved a referendum, yet history may judge Salmond more harshly for losing it on such a shaky prospectus.

His other claim was that free university tuition was great – he even had a statue made commemorating the policy.

The evidence clearly shows that free tuition has not expanded access to college for students from poorer areas and perversely, may have resulted in Scots students being turned down for university places in favour of fee-paying foreigners. The once all-mighty Salmond looks much less substantial now than he did in office.

As for Cameron, he too struggles for a positive legacy.

In his own estimation, gay marriage is his great achievement – not something he or others could have predicted as the pinnacle of six years in Downing Street.

No statue

So far there are no statues to Cameron’s term in office and a consensus has formed that it is something of a disaster.

The lesson of both men is that day-to-day governing is great fun and all-consuming but may not actually amount to that much.

Sturgeon and May both emit a sense that they want substantial legacies – to be remembered as reformers and doers.

In this, May could be one of the great prime ministers but it is not clear how history will judge Sturgeon.

Her delicate advocacy of independence might be spot-on but if May’s Brexit deal passes and Scotland’s position hasn’t been protected or enhanced, then the SNP’s leverage is gone for ever, the leadership exposed as the kind of disingenuous elite so despised elsewhere.

The other worry for Nicola is that, with 50% of Holyrood’s funding soon dependent on Scottish income tax revenue, she may be in charge when budgets shrink.

May too will be worrying that a weak economy is growing more frail by the day – both have to conjure up something clever to fix the problem.

Just when everything looked so different, two women with a lot in common – maybe there is hope in that for all of us.