“I cannae wait to get oot o’ this s********” was a riposte I often used to hear from the natives of Dundee growing up here in the 1990s.

By 1997, 1,000 people were leaving the city each year to pursue opportunities anywhere but here so it is quite the juxtaposition to now be listed among the Wall Street Journal’s Top 10 “hot destinations” and described by GQ magazine as “the coolest little city in Britain”.

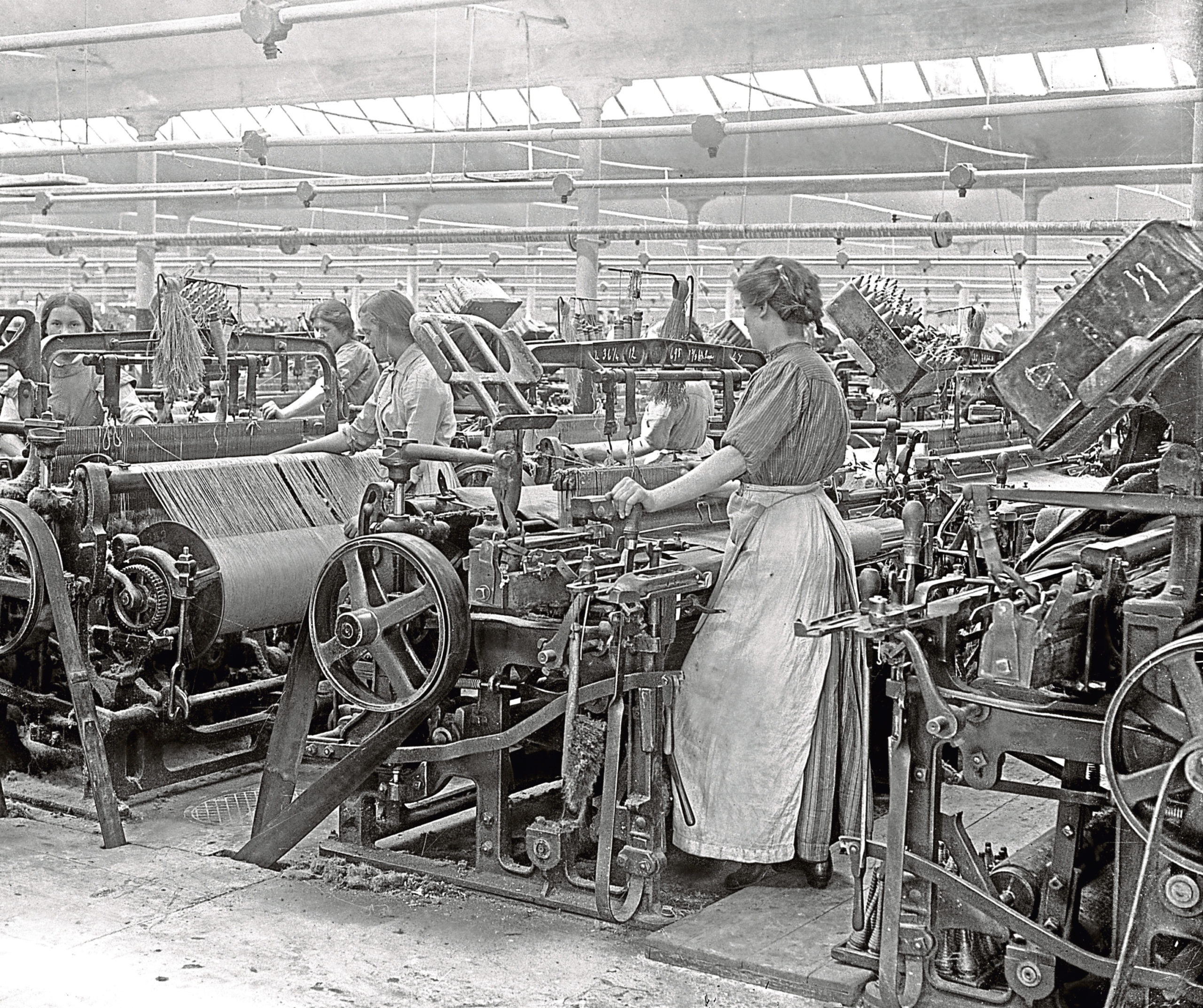

Jute, jam and journalism were the three recognised pillars of Dundee’s industrial heritage.

The last five decades, however, have seen our other big cities set out their stall to secure a stake in Scotland’s future.

Edinburgh is revered as our country’s capital, Glasgow as the city of culture and Aberdeen as the commercial centrepiece – but where does Dundee fit into this emerging mosaic?

There has been an implicit sense that the deindustrialisation of Dundee had left our city behind.

At its height, the jute industry employed more than 40% of the working population of the city before the jobs were exported to India and the last mill closed in 1970.

Then, Mackay’s jam moved from its roots on the edge of Dundee’s east end to Arbroath, taking several hundred jobs with it, more than a decade ago.

Last year, my family went to the Beano exhibition at The McManus across from the headquarters of DC Thomson, which is home to the one final pillar that is holding up our historical heritage.

The exhibition featured a portrait of Sir John Leng, who wanted to create an affordable paper for the working classes.

In 1877, the first edition of the Evening Telegraph was printed and retailed for the modest cost of half a penny.

There are three other words which now come to mind when I think of Dundee: poverty, politics and people.

Poverty moved in like an unwelcome lodger just as soon as jute vacated the city.

Politics became a mechanism for the working classes to amplify their unheard voices.

And, though manufacturing industries have come and gone, Dundee’s finest commodity has always been its people, who are the true lifeblood.

There is little doubt these three Ps are stitched together by the working classes.

More than 140 years on from the birth of “the Tully” and there is as strong a need for a working class voice as ever.

It is a voice that is currently absent in our press and our politics.

This is one of the few remaining papers you can purchase for less than £1 with access to writers who live in slums, rather than suburbs, and a political perspective from people who know more about poverty than prosperity.

The working-class people of Dundee are the incarnation of the warmth that makes it such a “hot destination” and as our city sheds the dead skin of austerity in pursuit of a future marked by prosperity, it is high time that we maximise the marginalised voices of those who, as political activist Arundhati Roy once said, are not voiceless but just preferably unheard.