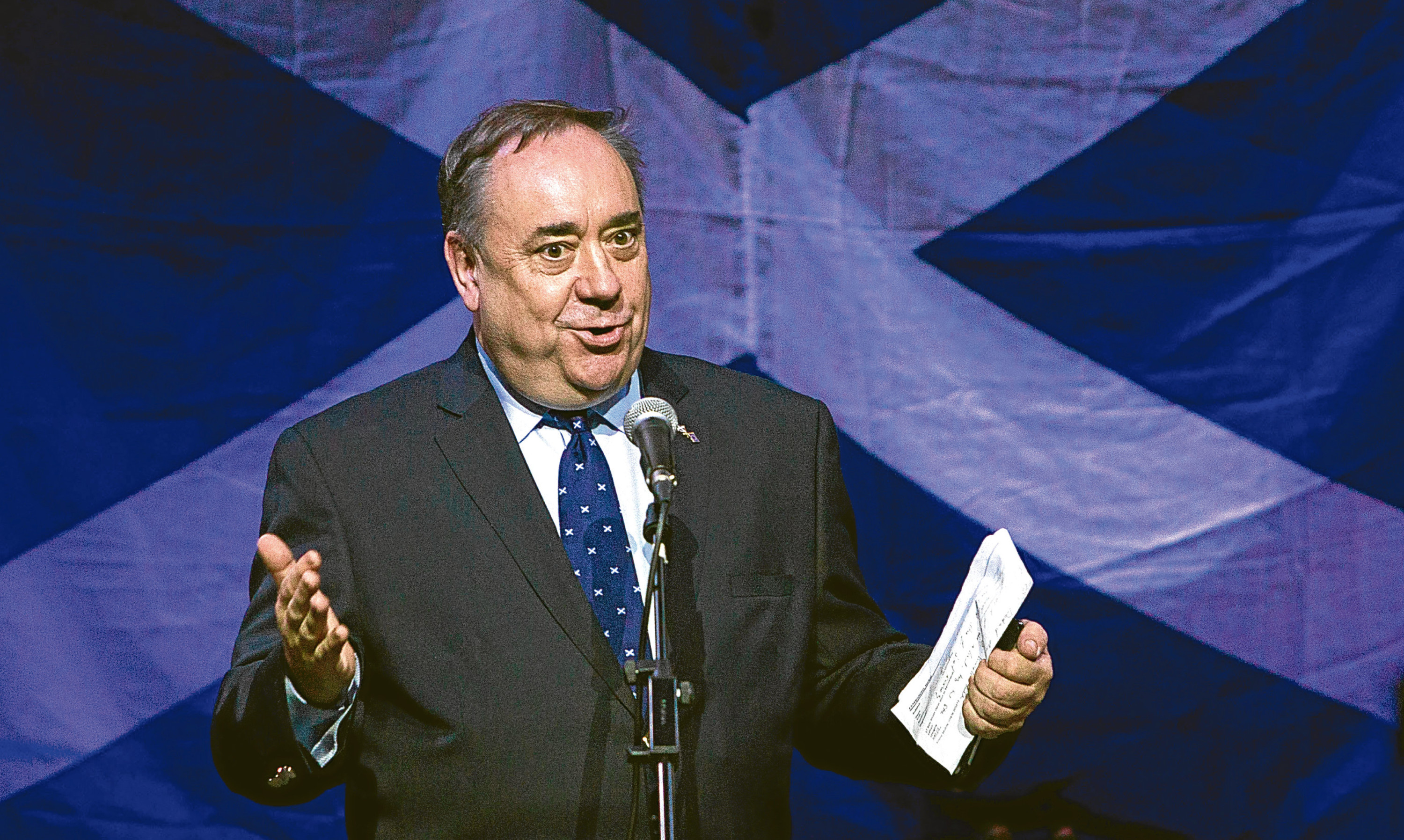

Something strange has been happening in Scottish politics recently. I don’t mean the reappearance of Alex Salmond, although that is strange too.

The former first minister has drawn attention to himself as Scotland marks the second anniversary of its independence referendum, a ballot which Salmond lost pretty convincingly.

Why he should want to play so central a role in what should be sad commemorations for his party, one can only guess.

On Sunday he headed up a rally in Glasgow, where he relaunched the grassroots Scottish Independence Convention and insisted another plebiscite could be on the cards in two years.

He also popped up last Friday to say Scots could go to the polls in 2018, even before the Brexit negotiations had been completed.

He seemed to be almost goading his successor – he called a referendum, he said, when support for independence was at 27% so Nicola Sturgeon wouldn’t be “too concerned about starting off with 48%”, the current level.

What he failed to mention was that his call was a bad one. Scotland opted to remain within the UK and the constitutional question was supposedly answered for a generation.

Those of us with longer memories than many Nationalists will recall Salmond had to quit the political stage here with his tail between his legs, after failing to deliver his life’s ambition and dashing the hopes and dreams of the 46% of Scots who voted yes in 2014.

It was a sorry episode for separatism and particularly for the man who drove the campaign.

The next act in the long-running Salmond saga was to be played out in Westminster, where he won a seat in the 2015 general election.

However, his decision to meddle in his old patch suggests London has not been the distraction he expected.

Pining for the limelight perhaps, the temptation of hundreds of salivating secessionists and standing ovations proved too much.

He clearly believes Scotland has missed him as much as he has missed it and is offering us his services again – whether we want them or not.

But there has been a decisive shift in the political mood north of the border which makes him look out of touch. In the past week, polls have shown Theresa May’s approval ratings in Scotland are higher than Sturgeon’s.

There is only a two-point difference but given political patterns in Scotland in recent years, which have seen the rise and rise of the SNP, it is remarkable for a Conservative prime minister to emerge ahead of Sturgeon in the popularity stakes.

Ruth Davidson, the Scottish Tory leader, is a clear 17 points in front of the first minister. On top of this evidence that voters are becoming increasingly disillusioned with the one-party-state politics of the Nationalists, some two-thirds of Scots have now said they don’t want another referendum before the UK formally leaves the EU.

There are plenty of reasons for the electorate to be dissatisfied with the regime at Holyrood.

Not least of these is the £15 billion deficit we would be faced with if we were to leave the union, according to the government’s own figures.

It is no surprise Alex Salmond ignores these signs of public unease; he didn’t get where he is today by listening to the quiet majority.

However, it is extraordinary that Sturgeon has chosen to follow him down the fundamentalist path of nationalism at any cost.

Writing in a pro-Nationalist paper on Sunday, Sturgeon – the person appointed to represent all Scots – declared independence was more important than trifling matters such as the economy and future prosperity of her country.

“The case for full self-government ultimately transcends the issues of Brexit, of oil, of national wealth and balance sheets and of passing political fads and trends,” she said.

Her message now is that separation may well ruin us but so what.

Wiser counsel within the party, startled one assumes by Salmond and then Sturgeon’s outbursts, have advocated a more pragmatic approach.

Other senior SNP insiders are reportedly urging caution too. They will be alarmed, not just by reckless calls for a vote they can’t win but by their leaders’, past and present, disdain for the everyday concerns of ordinary Scots.