They all laughed at Christopher Columbus when he said the world was round, as the great lyricist Ira Gershwin wrote.

Of course, they should have laughed at Gershwin because Columbus didn’t set sail to prove the world round – that was well known. He went to a find a new world.

This proves two things – people often laugh at the new and ridicule innovators, plus people often get the wrong end of the stick.

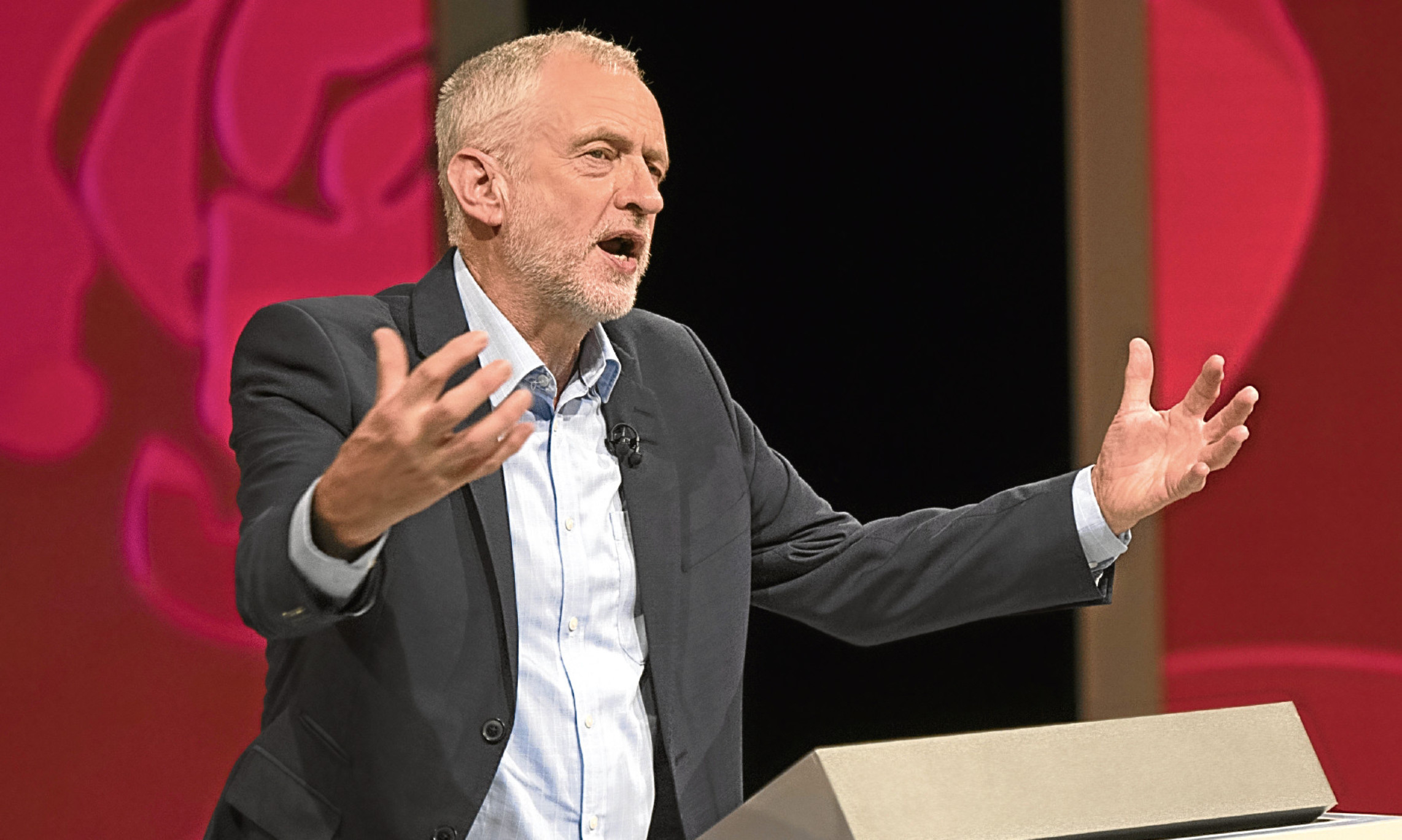

Both factors can be said to apply to Jeremy Corbyn.

I’m not suggesting he’s up there with Columbus but he’s certainly the victim of skewed perception and knee-jerk mockery.

Voting has closed for the Labour leadership and, by Saturday, Corbyn is expected to be returned as the man in charge, though quite what he’ll be in charge of is unclear.

Fractured

There remains something called the Labour Party but it is so fractured it exists in its own category.

Voter allegiance tends to lag behind political reality – we take a long time to finally accept a party is not what we remembered or hoped it to be.

For this reason, in the event of a general election or by-election, Labour is still in with a fight.

In fact, since Corbyn took over, there is no sign of the party simply disappearing from the electoral field. Around 30% say they’ll vote Labour at the next general election.

At the moment, it is not about to be blasted from the public arena as the Liberal Democrats were in 2015.

However, nor is the party on the verge of victory.

It may still win many constituencies but nowhere near enough to form a government in Westminster.

That is the dilemma – is the more fundamentalist leftism of Corbyn worth sticking with in the hope it eventually wins over large support or will it never appeal to enough English voters, thus locking Labour out of power for the foreseeable future?

The party’s MPs are convinced of the latter.

They want a new leader and new direction, convinced British politics has forever moved on from major ideological divides into an era of managerial politics where the most plausible chief executive is most likely to claim Downing Street.

Corbyn and his fans think this managerialism is what has created the great wealth divide and is exactly what needs to be challenged with strong alternatives – none of which include a drift to yet more neo-liberal globalisation.

The story that’s being run is that the Tories are centrist while Labour dies on dogma.

It’s not true – Theresa May leads a highly dogmatic Conservative party.

It is against state ownership, for grammar schools and against the European Union.

These are not pragmatic positions but ideological ones.

We can’t say Corbyn is free of dogma but in contrast, he looks less rigid than his chief political opponent.

Often right

What’s more, he has the advantage of often being right.

Had Labour listened to Corbyn, the UK might not have gone to war with Iraq or attacked Libya.

The pressure to renew Trident wouldn’t be so great.

Hinkley Point, the nuclear folly on England’s south coast, would not have been given the green light.

This seems important – Corbyn himself may have acquired the loser image but history often proves him right.

Had his sceptical view of the EU prevailed, the dissatisfied voters in England may have had somewhere to go as Europe expanded from 12 members to 28 over the 1990s and 2000s.

People who wanted to be heard – who wanted to say globalisation was not working for them – might have found a home in a Labour Party that was pro-EU reform.

Perhaps this is all easy to observe with hindsight and no doubt some of Corbyn’s views appear tediously dogmatic – such as the anti-Zionism – but a world in which his views prevailed would be different and, quite possibly, better.

That’s why it is hard to like the Labour MPs desperately fighting for their job – too many appear too woolly to care for.

People who came in on Blair’s coat-tails not only have had their moment in the sun but also helped to burn the principles of the party.

They accuse Corbyn of outrageous extremities, when its not evident he espouses such radicalism.

Rather, the overwhelming impression of one year of Corbyn is that he has a fondness for the fundamentals of the left but quite a flexible view on how to achieve them.

In this he has a certain comradeship with Labour’s first leader, Keir Hardie.

Hardie was a man of the left but without dogma or rigid ideology.

The great Scots politician was more a champion – someone who fitted into the former Labour leader John Smith’s description of the movement as a “crusade”.

I don’t think Corbyn is right for Labour – he lacks the grace to lead a fractured party and has yet to develop a coherent political alternative.

But we do him and the anger of the people a disservice if we imagine him a tramp or a trickster. He is in search of a new world and those who laugh should ask themselves why.