The grey geese are back. Regular readers will know how I look out for their return each autumn. They are the elemental spirits of nature, the authentic voice of winter.

They have spent the summer at their breeding grounds in Greenland, Iceland and Spitsbergen. Their young are fledged and now grazing is getting scarce.

About this time each year they sniff the chill winter winds from the north and know it is time to answer the irresistible call to fly south, following immemorial flight lines, more than a thousand miles to escape the Arctic winter for our more benign climate.

I’ll be looking out for their straggling chevrons beating down the Howe of Strathmore.

Almost as if I was subconsciously listening out for them, I was woken last Sunday morning, about 5.15am, by their “cryin’ voices trailed ahint them on the air”. I was only half awake but it seemed the deeper notes of the arrivals, as they swept over our roof, were the calls of greylag.

Inka and I are enjoying new walks in the stubble fields. There’s a great variety of walks round here but a change is as good as a holiday, even for a dog. Some fields are left for the winter but most will soon be ploughed in readiness for drilling winter barley and wheat.

Wee Macbeth, who was closer to nature than most of the world, on account of his wee, sawn-off legs hated walking in stubbles. The stiff stalks scratched his tummy and made him very short tempered.

Another harvest

There’s another harvest too. Horse chestnut trees are shedding their conkers. The ground beneath a tree near the house is littered with their empty, green shells but no nuts. I hope the local kids have been round picking them up for conker fights.

A field in permanent pasture, at the back of the Big Hoose, has half a dozen venerable oak trees covered in acorns. The pigeons will be flocking for them when they start to fall.

I once killed a woodpigeon which was too slow off the mark as I drove past it. I went back to collect the carcase – there’s nothing wrong with fresh roadkill. I plucked it and, as I cleaned it, the crop burst open and beech mast spewed out all over the kitchen table. Pigeons must have pretty potent digestive juices to cope with that sort of a diet.

The pheasant shooting season starts today but there are still a number of juvenile birds from late broods, with half-formed tails, running round the road verges where they come to get grit to assist their digestion.

If I’m walking Inka in the late afternoon I hear the klok, klokking of more mature cock pheasants passing the word down the wood that strangers are there.

It’s only the cock birds that call – hens make a hissing sound. During nesting the cocks stay pretty silent for obvious reasons and you’ll only hear their warning call if alarmed.

Another sign of autumn is the sun settling lower in the sky as the afternoons wear on. If the wind has fallen away and everything is calm, the dancing midges come out. They are bigger than the dreaded mozzies and don’t bite, and they perform an elaborate harvest dance in the shafts of sunlight among the trees.

Philosophy in miniature

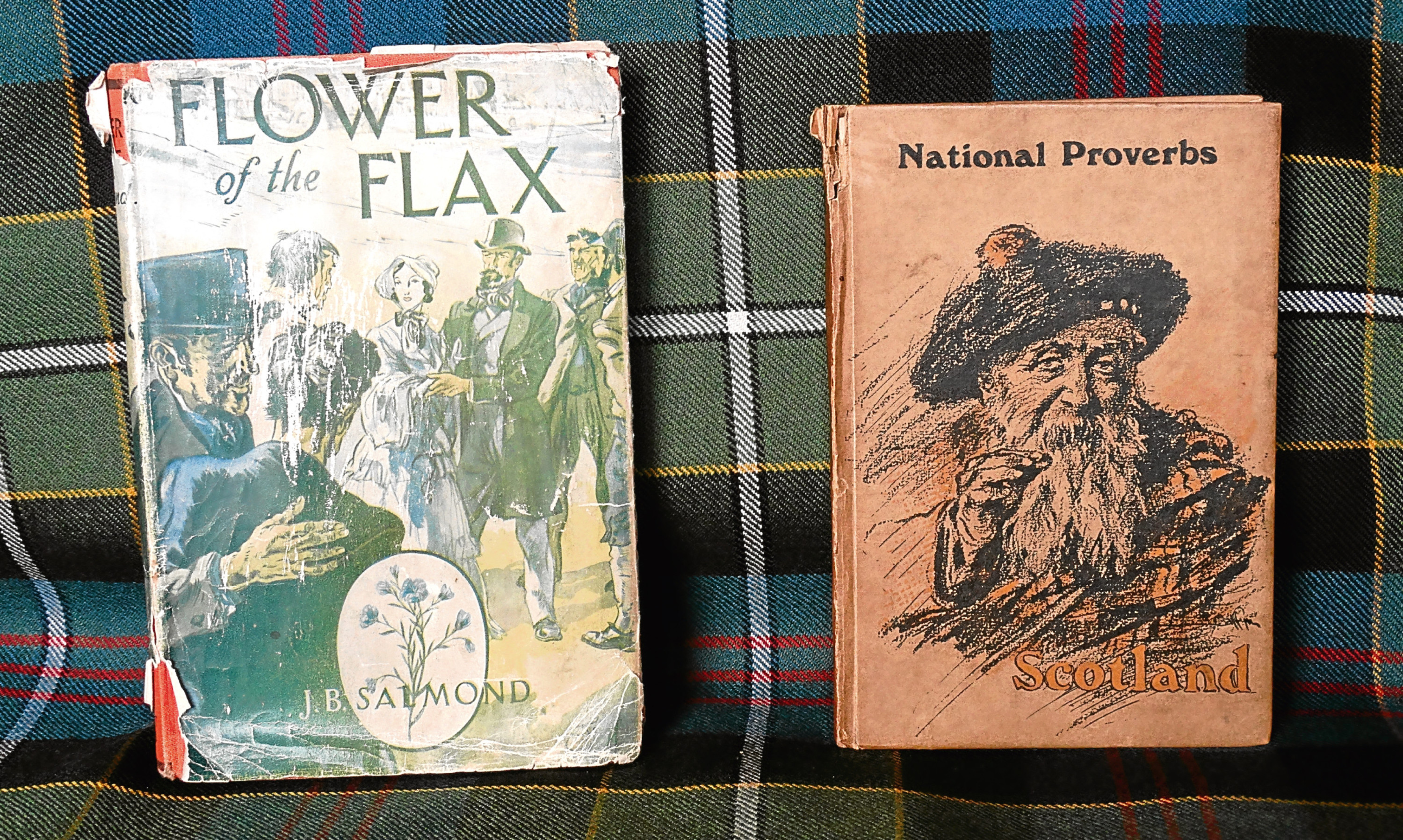

I have been given a book of Scottish National Proverbs which was published 100 years ago.

Its introduction begins “The proverbs of a nation are … (the) epitome of its wisdom”. Sometimes you can find a whole philosophy of life encapsulated in a handful of words.

I find it interesting that I recognise scarcely any of them.

It is inevitable that the tenor of our national wisdom has changed over the century but “A blind man’s wife needs nae painting” might be considered a tad insensitive today. So too “Naebody’s sweetheart’s ugly”. And “Ye’re nae chicken for a’ yer cheepin” probably invites a skelp round the ear.

On the other hand “Naething to be done in haste but grippin’ fleas” has the resonance of national wisdom about it for a nation that has confronted the Highland midge.

As for “Dinna lee for want of news”, perish the thought (Editor)!

“He slippit awa like a knotless thread”, meaning he had nothing to anchor his hold on life to, stirred a recent memory.

The expression “juist a knotless threid” comes in the novel Flower of the Flax, by JB Salmond (1891-1958) who was born in Arbroath.

He was commissioned into 7th Black Watch and saw action during the Battle of the Somme, one of the bloodiest military battles in history which was still being furiously fought on this date 100 years ago.

After the war he joined the staff of The Courier and in 1927 became editor of The Scots Magazine.

I’ll end with the strangest proverb in my wee book “Ne’er marry a widow unless her first man was hanged”. What a burden to put upon a widow who might be hoping for another chance.