Sometimes you just feel sick fed-up. This is one of those times.

Just shy of two years of restrictions due to a global pandemic, with Westminster politics playing out in a welter of arrogance, greed and lies, we feel disheartened, exploited and ignored.

Or speaking for myself, as a tax-paying, law-abiding, voting member of society, I feel like that.

And then something will come along to cheer you up.

How it started

Take the tale of @BootstrapCook Jack Monroe who, feeling sick-fed-up herself, tweeted angrily one morning that the method used to calculate inflation wasn’t good enough

Famous for campaigning for struggling families and highlighting poverty and hunger, Jack Monroe has long shone a light on affordable meals for people with little money.

The people who have to choose between eating or heating.

Jack speaks her mind, she is funny and articulate, and she uses facts like a lightsaber.

On the morning of January 19 she fired off a tweet.

“Woke up this morning to the radio talking about the cost of living rising a further 5%,” she said.

“It infuriates me the index they use for this calculation, that grossly underestimates the real cost of inflation as it happens to people with the least. Allow me to briefly explain.”

And she did.

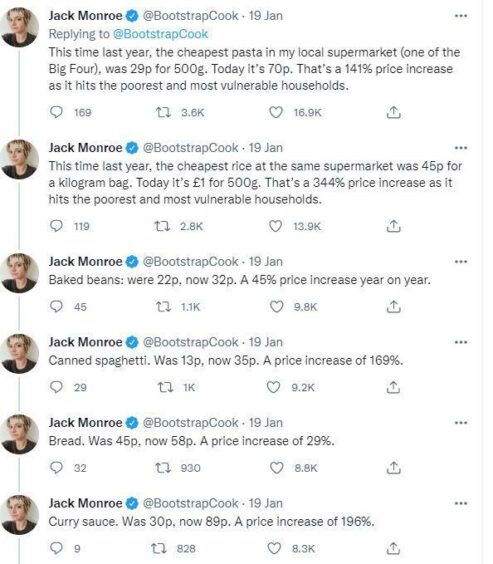

This time last year the cheapest pasta in her local supermarket was 29p for 500g, today it is 70p – a 141 per cent increase.

The cheapest rice in the same Big Four store was 45p for a kilogram bag. Today it is £1 for a 500g bag, an increase of 344%.

The examples kept coming, all making the point that in real affordability terms spiralling prices of basic food items were hitting the poorest and most vulnerable people the hardest.

She pointed out that often the higher prices applied to greatly reduced quantities, while higher end supermarket chains had kept their meal deals at around £10 for years.

Jack, incidentally, has long publicised how to feed a family on £10 a week.

Her tweet took off. The next morning she noted 15 million people had read the thread and almost every media outlet was challenging the inflation figure.

How it’s going

It didn’t stop there. She vowed to compile an inflation index showing how soaring prices affected vulnerable people in real terms, how there are different realities to inflation.

She’d call it the Vimes Boot Index, after the Terry Pratchett character Sam Vines.

In the Discworld novel Men At Arms, Sam comes up with his Sam Vimes ‘Boots’ theory of socioeconomic unfairness – it has to do with the real cost of a good pair of boots.

Terry Pratchett’s estate jumped in, publicly giving Jack permission to use the name. Pratchett’s daughter, writer Rhianna Pratchett, said her father would have been proud to see it used in this way.

Next the Office of National Statistics got involved. Mike Hardie, ONS head of inflation statistics, said in a blog the published annual inflation rate – currently 5.4% – was an average for all households.

“But everyone has their own personal inflation rate,” he added.

Since then, Jack has been everywhere making her point – columns In major newspapers, interviews on radio and TV – while pointing out any fees earned “will be donated, as usual, to the Trussell Trust, as standard.”

A triumph for people power

On January 26, Jack tweeted: ”Delighted to be able to tell you that the @ONS have just announced that they are going to be changing the way they collect and report on the cost of food prices and inflation to take into consideration a wider range of income levels and household circumstances. #VimesBootsIndex.

It felt like a brief triumph for people power, and all thanks to one feisty campaigner.

Against this partygate unfolds, and its narrative of entitlement brings growing anger, disbelief and despair.

Devolved Scotland feels the consequences too. We have our own heartbreaking stories of loss, hardship and deprivation during Covid lockdowns, while they partied at No 10.

We’re watching the Westminster Government seemingly concentrate its efforts on preserving its own power rather than working for a country reeling from Covid, Brexit and the emotional and economic fallout.

Why is it left to private campaigners?

How is it left to private campaigners and lobbyists, like the Good Law Project, like Every Doctor, to hold a government to account?

It took the Good Law Project and Every Doctor a year and crowd-funded legal action until a recent High Court decision ruled the Westminster Government’s fast-track VIP lane for awarding lucrative PPE contracts to those with political connections was unlawful.

Since then, news broke that Chancellor Rishi Sunak has written off an estimated £4.3 billion in fraudulently claimed Covid relief. Treasury minister Lord Agnew resigned in vocal protest.

On January 20, while 15 million people were reading Jack Monroe’s tweets, Foreign Secretary Liz Truss landed in Australia on a private jet at a cost of £500,000 to taxpayers.

Put those figures against the Scottish Government’s record £18 billion funding for Health and Social Care announced in December, and it seems less like Monopoly money and more like money that could be better spent.

Or, put that against a family having to choose between heating and eating.

How did it come to this? We are wealthier and apparently better educated than ever.

It’s a very long time since ancient Sumerians ‘invented’ writing some time between 3,500 BC and 3,000 BC. UNESCO estimated 86.2% of the world’s adult population were literate by 2015.

We have the opportunity to learn for ourselves.

Living in a strange paradox

It’s a long time since glimmers of democracy began in the UK in the 15th Century. Universal suffrage was finally granted to women here in 1928.

Yet now we live in a strange paradox, where governments can seem to be working against us and for themselves.

Sometimes our belief that leaders are our democratic representatives, with our best interests at heart, seems naïve and quaint.

Partygate, and that cake, are reported to have alienated young people further, the very people we need to lead us tomorrow.

Besides anger, there’s a sense of futility, that anything we do is pointless.

But that’s not true, not if we educate ourselves.

And not if we look further than the echo-chamber of social media and the confected culture of aspiration that sees many young people wanting to be like a perma-tanned celebrity on a yacht, rather than a NHS worker who makes a real difference to people’s lives.

Sometimes the good people do win.