This week’s conference is crunch time for the SNP and there is a growing acceptance among party elders that they have reached a crossroads.

Nicola Sturgeon must see it too but that will not make the next three days in Glasgow any easier for her.

A year ago, fresh from the Nationalists’ stunning success in the 2015 general election, in which they won all but three of Scotland’s Westminster seats, the party was on a high.

As Sturgeon told excited delegates back then, membership had soared from about 25,000 before the independence referendum the previous year to a figure approaching 120,000.

Today, it is even higher but the mood and the momentum has changed – and not in a way Sturgeon and her closest advisers could have predicted.

Last year, she had to calm the jubilant crowds clamouring, in the wake of SNP electoral triumph, for a rerun of the September 2014 referendum.

Public opinion was not on the separatists’ side – yet; some dramatic realignment would be needed before separation could be put back on the table.

The masses of new members were temporarily placated but restless. Then, against everyone’s expectations, that realignment came this June when Britain but not Scotland voted to leave the EU.

Sturgeon, cheered on by her predecessor Alex Salmond, had the trigger she needed to keep those secessionist hopes alive and in the post-Brexit hysteria, she threw caution to the wind.

A new vote on independence was now “highly likely” to protect Scotland’s interests in Europe, she said. With almost two-thirds of Scots backing the Remain camp, she calculated support for Scottish nationalism would flourish among disappointed Unionists.

She was wrong.

Voters are largely where they were on the UK constitution before June 23 and an increasing majority are opposed to the SNP’s plans for another ruinous plebiscite.

People in this country may hate the thought of leaving the EU but that has not altered their attachment to the rest of Britain, to which we are bound more deeply, by tradition and trade, than to Europe.

There is also the matter of some 400,000 SNP voters who were “Leavers”, an inconvenient fact Sturgeon has not acknowledged as she seeks an anti-Brexit consensus.

Her ministers may still try to whip up indignation over the EU but pragmatists on all sides are reviewing the landscape and finding Scotland has already moved on.

The latest to offer her advice was Scottish academic Professor Jim Gallagher, who urged Sturgeon to forget independence and focus on securing new powers over areas such as agriculture, fisheries and the environment.

Scotland had an opportunity to “reset” its relationship with the UK, he said, warning that another independence ballot could create deeper divisions than the EU vote.

Gallagher was a high-profile campaigner for Better Together so Sturgeon will not care much what he says now.

However, his views are almost identical to those of SNP veteran Alex Neil, who voiced his concerns recently over fighting a referendum again.

Also adding his weight to the neo-realists is former justice minister Kenny MacAskill, who wrote a newspaper article on Sunday advising Sturgeon against a second vote and saying her agenda was marked more by “timidity than radicalism”.

MacAskill actually said much the same a month ago, for all the good it did. A further defeat over independence would “put the dream back catastrophically’, he said then.

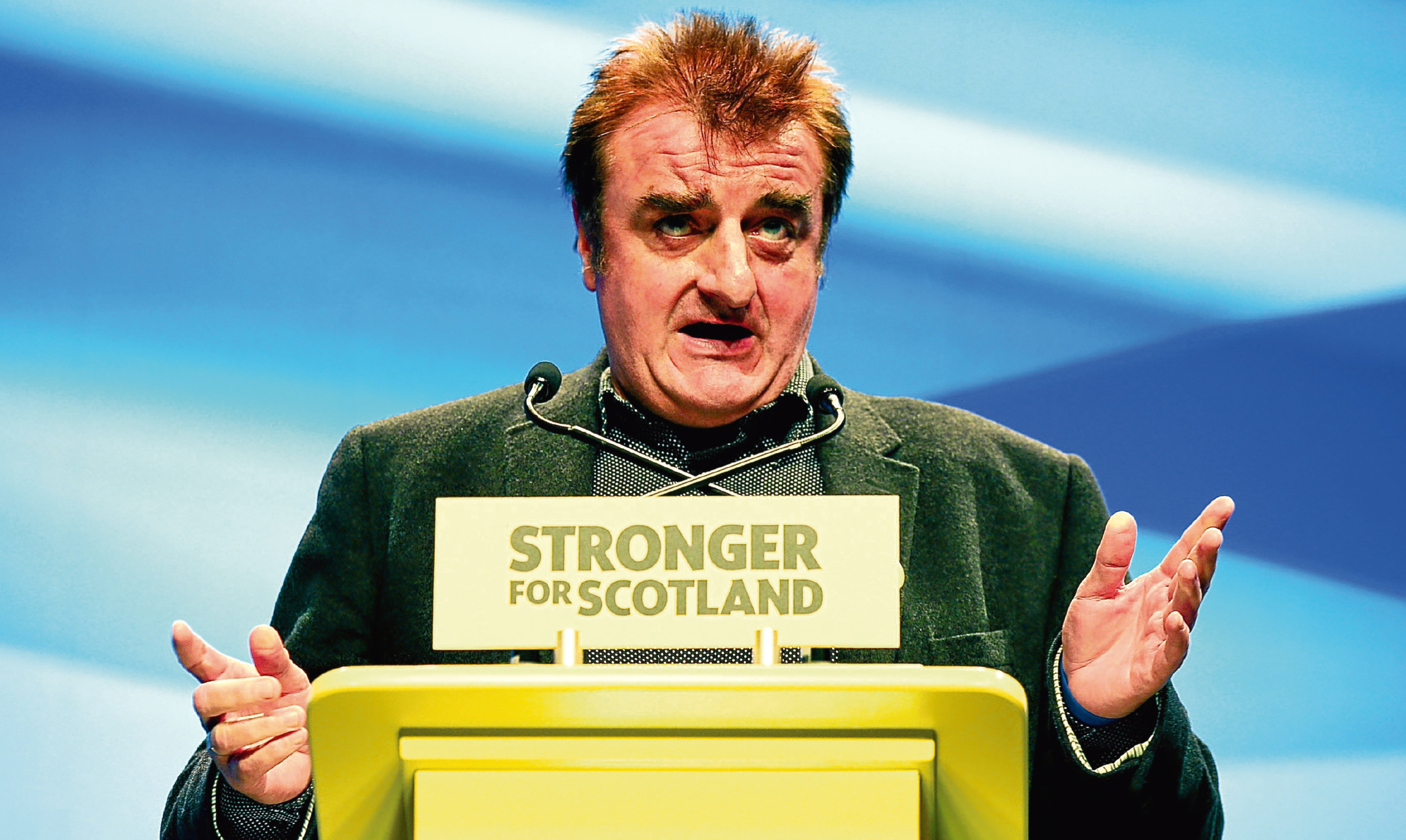

Now a more worrying critic has emerged. Tommy Sheppard, a late convert to nationalism but an SNP MP and a possible upset candidate for deputy leader (we will know the result of that contest and whether he has seen off Angus Robertson tomorrow), has spoken out against his leader.

While canvassing, Sheppard found thousands of party activists – that is, the loyal and long-serving foot soldiers rather than the impressionable new guard – distinctly unenthusiastic about a fresh poll linked to the Brexit vote.

The straight-talking member for Edinburgh East said party stalwarts knew they only had one more chance and there was “no room for mistakes”.

“There is no drive among the activist corps for saying let’s rush into something. There is a degree of thoughtfulness that is remarkable,” he said.

It is remarkable because it is so out of step with what the leadership has been urging.

Sturgeon, as she faces her conference, can heed this wise counsel and shelve her nationalist ambitions.

That would mean no more hiding behind independence rhetoric but becoming, for the first time, the head of a government instead of a protest movement.

Difficult domestic decisions would have to be made, radicalism in policy would need to be considered but the constitution would be, for the foreseeable future, a dead cause.

Or she can do the opposite, carry out her threat and set the referendum wrecking ball rolling. The time for stalling is past.