On the surface, Nicola Sturgeon and Theresa May don’t appear to have many similarities (apart from the obvious ones, that is).

But though they may seem polls apart politically, their current challenges as leaders are not so different.

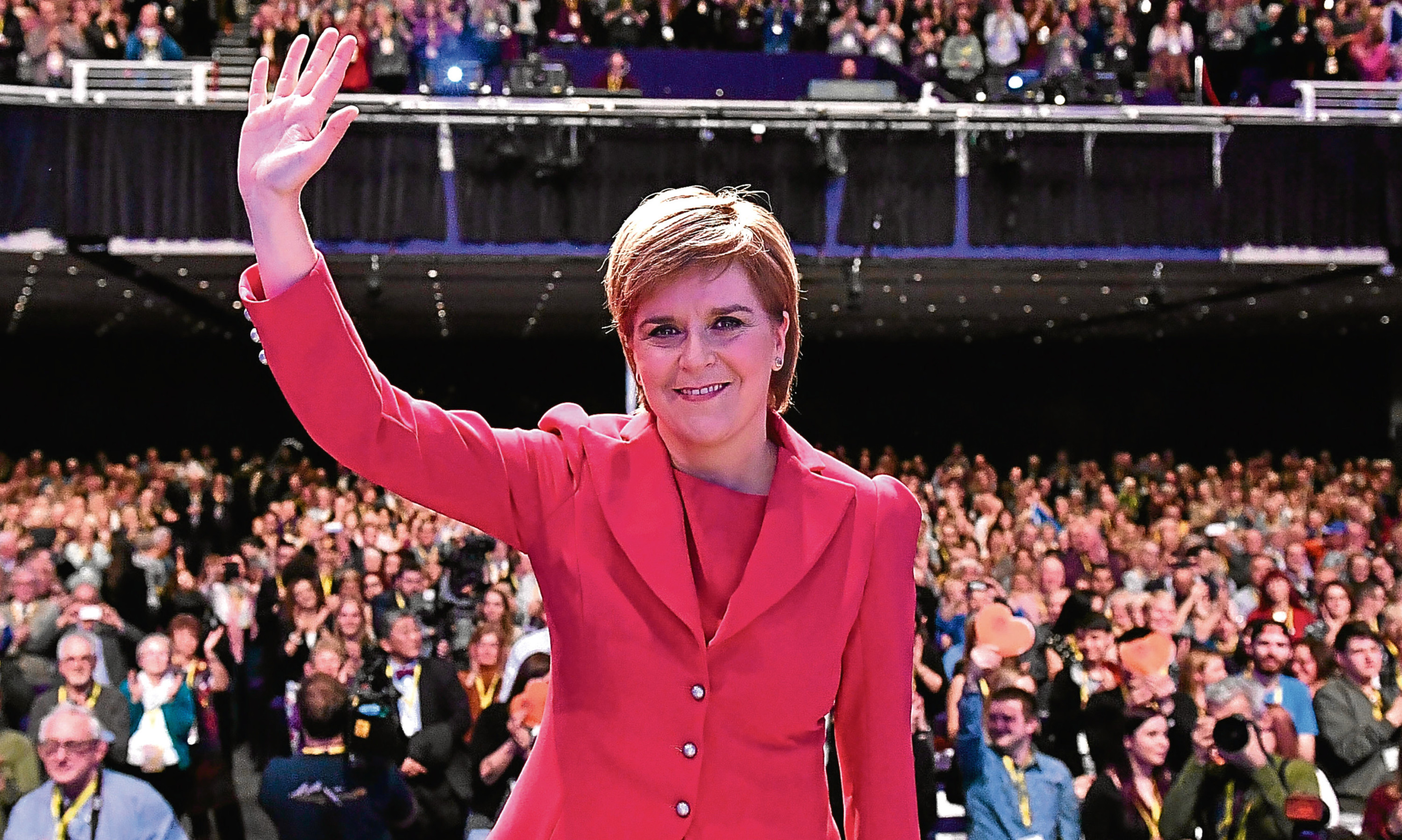

Sturgeon has just emerged from another party conference, triumphantly if you go by the clapometer and the standing ovations from devoted members.

However, on closer inspection she is not the invincible conqueror of a year ago, fresh then from the SNP’s incredible general election success.

Her own approval ratings with Scots have dropped below two Tories – May and the Scottish leader Ruth Davidson – which would have been unthinkable until quite recently.

And even among Nationalists she no longer commands unquestioning allegiance. On Sunday, her new deputy, Angus Robertson, contradicted her stance on a second independence referendum, saying during a BBC interview that the SNP would drop its threat if its demands over Brexit were met.

Earlier, Sturgeon had said exactly the opposite, warning Scotland was “highly likely” to opt for another ballot by 2020 and accusing May of not treating her as an equal partner.

There have been other contrary voices of late, most notably from SNP ex-ministers Alex Neil and Kenny MacAskill, both concerned that the First Minister’s backing for a new independence plebiscite is reckless given the opinion polls and could set back the separatists’ cause for generations.

Then, at a Glasgow fringe meeting, Alex Salmond’s former chief of staff, Geoff Aberdein, suggested Sturgeon should hold a referendum now because this might be her last chance before her popularity wanes.

Sturgeon’s dilemma has been to balance the party members, eager to reignite the Yes campaign, against the realists who predict (quite realistically) a second defeat and advise caution.

The fact that she has unequivocally sided with the Yessers for now doesn’t necessarily mean she wants to rush into a referendum.

Although her talk is fighting, she is deploying her range of stalling tactics.

May also has a dilemma between the EU Leavers and Remainers in her party. But unlike Sturgeon, she is also considering the wider electorate, who made their views known in the European referendum in June.

The Prime Minister has alarmed the middle ground by adopting a “hard” Brexit tone, although she wasn’t in favour of Brexit at all before she entered Downing Street – or if she was, she kept very quiet about it.

She used her party conference to announce Britain will leave the single market and she has refused to consult Parliament over the terms of withdrawal.

The consequences of Brexit so far have been a dramatic drop in sterling – reportedly to its lowest level since 1848 – and the Governor of the Bank of England said there would be inflation on food prices. Motorists could be in for steep hikes too.

While the rest of Europe waits to see what trade deals the UK negotiates, May must try to keep the economy on track and her ministers on board.

She is walking a tightrope between the majority – in her party and country – who crave a clean break with Brussels, and the 42%, including most Scots, who feel betrayed by their fellow Brits.

It is the Brexiteers who seem to be having it all their own way but could May be engaging in a game of bluff?

In the New Statesman, George Eaton argues the PM has actually embarked on compromise. In her conference speech she said the EU wheeling and dealing would “require some give and take”.

Eaton says: “By embracing hard Brexit, she has bought valuable trust and goodwill. Only in time will her strategy become clear to all. May has gone out hard to better soften later.”

If he is right, Sturgeon’s focus on the toxic Tories in her speech on Sunday was not only unimaginative but naive. The SNP leader’s overblown rhetoric gives her little room for manoeuvre; she could learn much from May’s more considered approach.

But she won’t. Imagine Sturgeon saying her Brexit talks with London would “require some give and take”. That is the glaring difference between these two leaders.

The “will she or won’t she” bluff that Sturgeon indulges in to prolong the pro-independence dream will come to nothing because she knows she can’t win this one.

May, who has been silent on the subject of a snap election, is far better placed than Sturgeon to force voters back to the polls. Her party has a 17-point lead, Labour is in disarray and she could increase her thin Commons majority substantially if there was a vote tomorrow. She might even win a few more seats in Scotland.

With a clear mandate, May would be able to face down the most ardent Leavers – and also scare the living daylights out of the noisy Scottish Nationalists. What a tempting prospect.