The word ‘nationalism’ has clear connotations wherever it is associated with political movements, across the world and across the ages.

In its worst case scenarios nationalism brought Europe the National Socialists – better known as the Nazis – in the first half of the twentieth century, and South Africa the apartheid era, introduced by the National Party of DF Malan in 1948.

In Europe today it is still associated with the far right and white supremacy – see Marine le Pen’s Front National in France and the Dutch nationalists of the Party for Freedom.

Against this background, Scotland’s brand of nationalism is a far more benign kind of politics. These days it places itself firmly on the left, is avidly pro-immigration and promotes ‘inclusiveness’.

To suggest anything else – that this country’s version of nationalism is not quite the all embracing concept its apologists claim it is – predictably prompts howls of outrage.

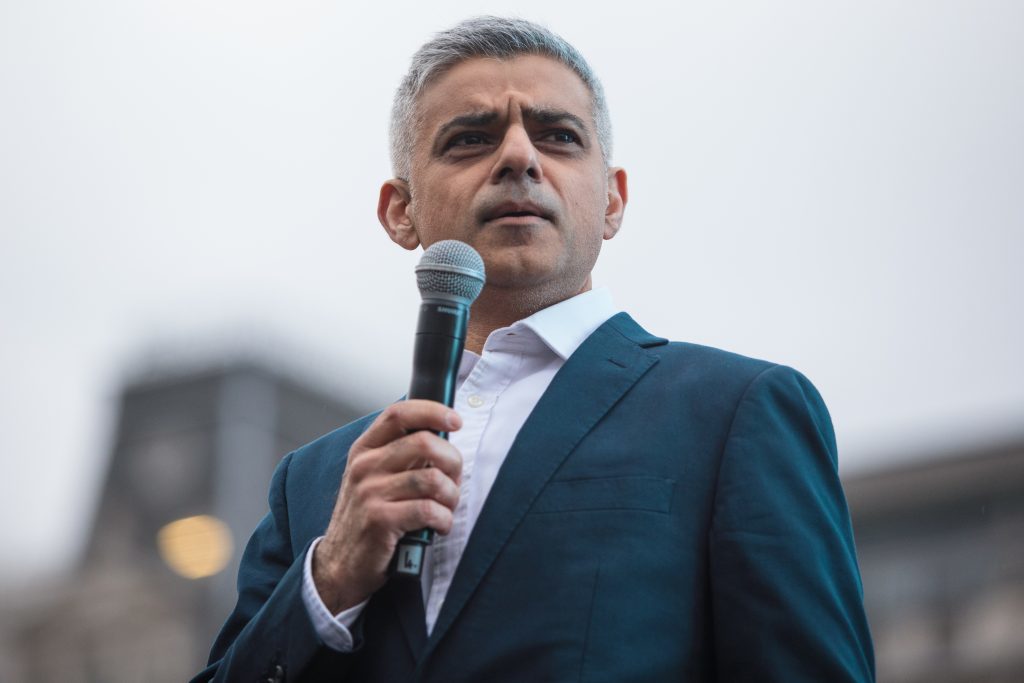

So when the London mayor and Labour politician Sadiq Khan wrote a speech saying there was ‘no difference’ between ‘those who try to divide us on the basis of whether we’re English or Scottish, and those who try to divide us on the basis of our background, race or religion’, condemnation from the SNP came quickly.

Scotland’s first minister Nicola Sturgeon, who has devoted most of her life to campaigning for Scottish nationalism, described Khan’s intervention as ‘an insult to all those Scots who support independence for reasons of inclusion and social justice’.

Khan clarified his comments, insisting he wasn’t saying Scottish nationalists are racist or bigoted but ‘now, more than ever, what we don’t need is more division’.

Later, in an interview with this paper’s Kieran Andrews, Khan warned of the rise of populist and narrow nationalist movements.

‘At a time when we are looking for an antidote to Trump and Brexit I don’t think we should start talking about separation.’

The SNP has always said it supports a civic nationalism, based on making an economic case for breaking up the UK. But we only have to look back two and a half years, to the independence referendum of 2014, to see that this is an idealistic view.

It may have once been the intention of leading Scottish nationalists to argue for secession on the grounds that it would devolve power and create opportunities.

But the campaign for Scottish independence has long since been hijacked by purer nationalists, who have narrowed the focus of the debate, as nationalists tend to do, to a them versus us contest.

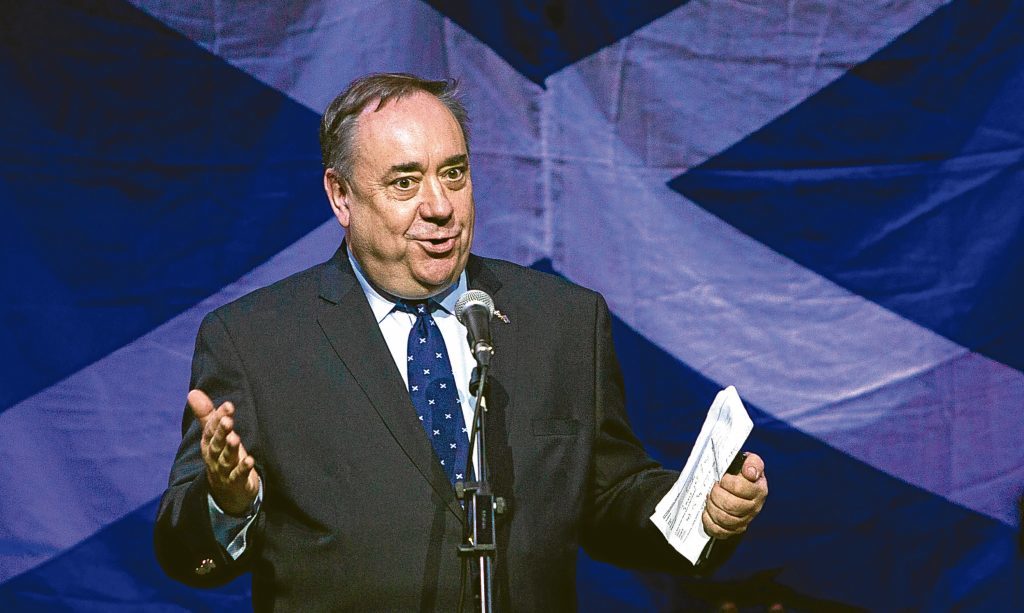

Alex Salmond, Sturgeon’s predecessor, was not necessarily the instigator of this more traditional form of nationalism but he certainly gave it a booming voice.

And Sturgeon has been as effective, if not more so, in fighting nationalism’s cause by sewing division. The ‘them’ is England, and more specifically, London, and she cannot deliver a speech or defend a policy without reference to this apparent foe.

So Scotland’s health service may be in dire straits but ministers do not need to fix it because England’s, so she tells us, is worse. Scotland’s business rates may be crippling enterprise but our entrepreneurs are not as badly off as England’s.

You could argue that the SNP can’t very well push their nationalist agenda any other way now, having been handed all the political powers they need to run the country separately, and at the same time having failed to come up with an economic strategy that would make a separate Scotland better off.

But by unleashing their attacks on the rest of the UK, they have legitimised the kind of nationalism they profess to deplore.

Salmond and Sturgeon possibly didn’t mean to inspire the uglier elements of xenophobia that nationalist groups breed, but they cannot deny that within their grassroots there are plenty of nationalists (a minority hopefully) who have signed up on the basis of hatred of the English.

The Scottish Labour MP Jackie Baillie, who was born in England, said, in defence of Khan: ‘If nationalism is not about racism why then do your supporters tell me to go home because of my accent?’

Are the English a different race to the Scottish? Racism may be the wrong word but ‘narrow’ and ‘prejudiced’ fit perfectly well.

While it is unfair to lump the loose cannons of the rank and file with a more principled leadership, nationalism by its very nature is about exclusion not inclusion.

Patriotism needs no enemy but nationalism demands one, said Douglas Alexander, a former Scottish Labour MP (though he is not the first to make that distinction).

If the SNP object to being linked with the unsavoury aspects of nationalism they could change their name or change their tactics. The problem is that their current popularity is built on an anti-England platform – take that away and what’s left?