Today, barring a very unlikely rebellion in SNP ranks, the Scottish Parliament will vote by a narrow margin for a second independence referendum.

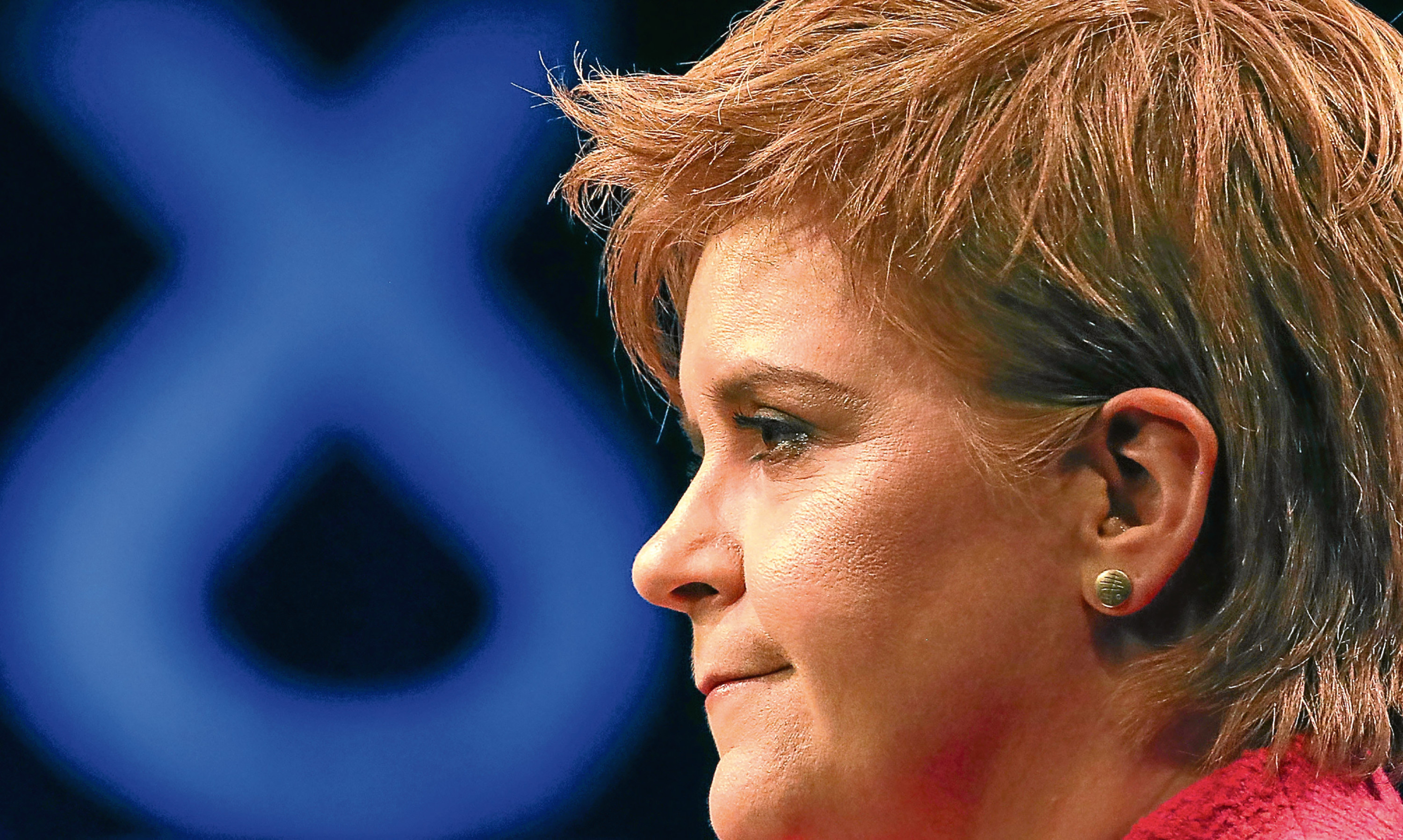

The Nationalists will bolster their slim majority with the Yes men and women on the Green benches and Nicola Sturgeon will say the people have decided.

She will then goad the British Prime Minister, whose permission she needs under the 1999 devolution settlement to trigger a constitutional ballot, although the PM last week firmly quashed hopes of another plebiscite this side of a Brexit deal.

Despite Theresa May’s insistence that a new vote now on separation would be unfair on Scottish voters as they would have no idea what they were voting for, Sturgeon means to press on regardless with her demands.

If the Nationalist leader did have momentum on her side and if there was indeed a clamour for a rerun of the 2014 referendum, then even the staunchest unionists would have to concede grudgingly that Sturgeon had a case.

But this is not so. Poll after poll confirms Scots are opposed to another ballot on breaking up Britain and support for secession has dropped below where it stood two and a half years ago.

Old ruse

Because she knows she is going against the nation’s wishes with her referendum obsession, Sturgeon has come up with an old ruse.

She has a “mandate”, she says – a “cast iron” mandate no less – to try to force a second vote on separation because the SNP’s 2016 manifesto pledged to do so if there was a significant and material change in circumstances, such as Scotland being taken out of the EU.

Apart from the obvious flaw in this argument, pointed out by May in the House of Commons, that the SNP failed to win an overall majority in last year’s Scottish elections, Sturgeon’s mandate is flimsy for other reasons.

Her party also made manifesto promises to improve the education, health, transport (the list goes on) of Scotland but as daily headlines suggest, they have done nothing of the sort.

The Courier brought news on Monday of operations cancelled at Perth Royal Infirmary due to a budget and staffing crisis. While patients paid the price for the government’s negligence, the health minister was at the SNP conference, joining in the referendum flag waving.

No doubt the education minister was there too, cheering on constitutional upheaval while Scotland’s “dumbed down” education plan, as a former chief inspector of schools put it, continues to fail pupils.

What mandate is more important, the one which Sturgeon claims she has to hold indyref2 or those other ones in the 2016 manifesto to do something concrete to make Scots’ lives better?

Besides, how can the First Minister argue that Brexit gives her a mandate when she now admits she is considering a “compromise position”, with an independent Scotland seeking single market, not full EU membership?

Rethink

Objections within her own party to Europe – 400,000 of her separatists voted to leave the EU last June – have belatedly forced her to rethink her commitment to Brussels, making a mockery of the mandate.

However, with no mandate she can always cite the will of the parliament. But can she?

The Scottish Labour Party reminds us that the SNP has on several occasions ignored the will of the parliament since last year’s election – over, for instance, NHS closures and keeping the Scottish Funding Council board, when ministers were defeated at Holyrood.

Why is it OK for the Scottish government to flout the Scottish parliament’s wishes but not OK for the Westminster government to do the same?

But going back to mandates, as Sturgeon surely will; all those opposed to independence in 2014, who voted in a fair and legal ballot for Scotland to stay in the UK, have a mandate.

And so does the British electorate, which voted last year to leave the European Union.

If the Nationalists can choose the democratic decisions that are valid and those that are not, according to whether they agree with them or not, then their version of democracy has no value.

Perhaps that is why both their current and previous leaders feel able to change the recorded versions of what they said about the last referendum.

Alex Salmond has gone so far as to deny he called the 2014 vote a “once in a lifetime” opportunity, though the evidence is plain enough.

We have a political leadership so hell bent on pursuing its Nationalist interests it has lost sight of the national interest.

If Scottish voters were given a referendum on whether the SNP should get on with governing Scotland or spend the next two, three, four or more years arguing about what they did or didn’t say in 2014, the result would be overwhelmingly in favour of the former.