So this is what history feels like. In two days the Scottish Parliament has voted to demand another referendum and the UK Government has begun to withdraw from the EU.

Turns out history is pretty banal – a series of stirring declarations, obscure motives and dull bureaucracy.

People seem to be taking this in their stride – we have wisely concluded that when there are few facts, strong opinions are pointless.

Of Brexit, we know very little.

Its not just Whitehall that’s on new ground, so too every other civil servant across the EU.

As the negotiations progress any number of surprising discoveries will be made.

None of us can meaningfully predict where the discussions will go.

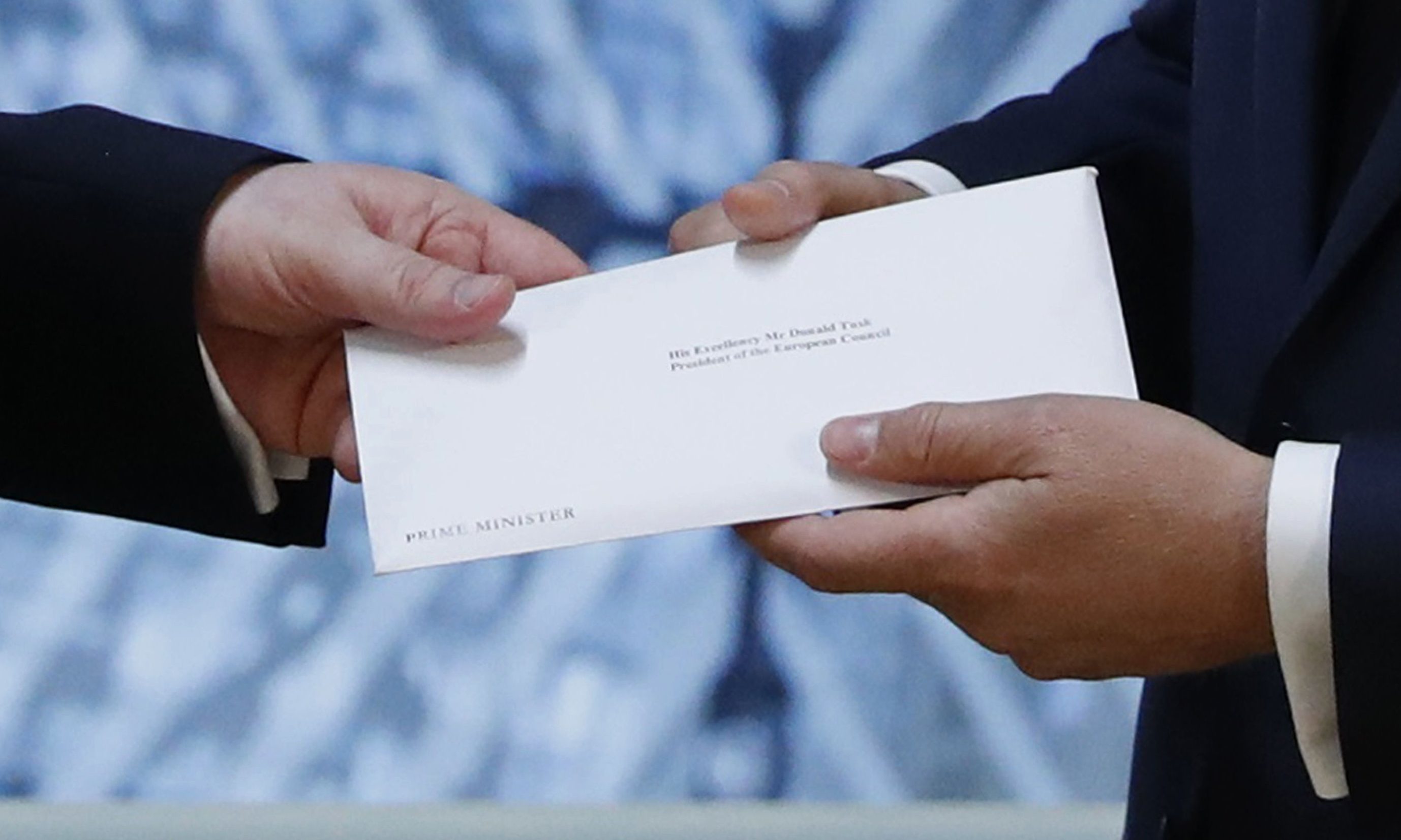

The UK Government has set out a White Paper, summarised in Britain’s letter to the EU President Donald Tusk that was handed over on Wednesday.

The EU is expected to publish its position – Brussels will deploy transparency as a negotiating tactic, a signal that it is far more open than the UK establishment would have us believe.

That suggests we can figure out the points of conflict and agreement.

Up to a point.

The history of the EU is about flexibility and creating apparent order whereas Whitehall is steeped in a tradition of fudge behind the facade of logic – both sides will compromise where pragmatic.

The EU has found a way of setting rules for 28 states while still accommodating local needs – it could not have grown without such fluidity.

London has extricated itself from countless colonies and in each instance, cocked up and compromised.

Examples from the last few months point to deal-making. The UK Government initially said it could live without the European arrest warrant, but then signed up to its continuation.

The UK Government indicated it would leave all EU regulatory bodies, but now suggests it would like to stay part of them.

A Sunday newspaper reports that Downing Street is thinking it will continue to pay benefits to EU migrants after Brexit – a solemn vow to the contrary was made during the referendum campaign.

May can allow the deal to evolve safe in the knowledge of two things.

The first is that each one of us has a different idea of what Brexit might mean – one person’s cave-in is another’s cunning deal-making.

Whatever agreement she strikes there will be something for everyone – while also being so complex as to be beyond ready characterisation.

Her second advantage is that it would be a very brave Tory rebel who rejected the final deal.

That would mean rejecting the UK Government’s negotiating ability – a treacherous strategy for even the most hardline Little Britain advocate.

By the time the negotiation is done, the mood will be to sign it.

That could mean Britain is still in the single market, party to most treaties and may even have to accept continued freedom of movement to prevent Brits abroad becoming illegal immigrants.

The UK Government will, when a final deal is on the table, have to promote it. May says “no deal is better than a bad deal” and that’s a fine opening shot, but no deal would signal a great failure on her behalf.

It would signal she isn’t a statesperson, but an agitator – and nothing about her career to date makes that likely.

So Downing Street would have to sell the deal to the British people, or they would be signalling they weren’t fit to be in government.

Do not mistake this for Polly Anna-ish optimism – the end result could be messy and we might all be paying the price for years to come.

What we can’t confidently do is predict it either way, and in that there is hope. As to what this means for Scotland is unknown.

The hoo-ha over another referendum has died down, a political baby met with great excitement but soon moved to an incubator, leaving everyone torn between dread and hope.

Independence may be the settled will of the Scottish Parliament, as voted for earlier this week, but what exactly that tells us is far from clear.

Sturgeon accused May of not knowing the answers to some Brexit questions. Possibly true, but Nicola is accused of exactly the same about independence.

The way the First Minister has positioned the need for a second vote is dependent on the Brexit negotiation.

She, too, has opted to appear defiant while being open to compromise.

The Scottish Government launched a demand for independence before spring 2019 on a Monday, and by Sunday this had become a vote at some time, following discussions, in which Scotland may or may not apply to rejoin the EU.

There just aren’t that many facts around, which means we shouldn’t be cast into gloom or ecstasy as this week ends.

The UK has pulled the trigger on leaving the EU, while the Scottish Parliament has asked for its own starting gun – historic dates, no doubt, but declarations so vague as to mean all and nothing.