In her search for someone to salvage her electoral hopes, Nicola Sturgeon has rather bizarrely alighted on Jeremy Corbyn.

She said she would consider supporting the Labour leader in the event of a hung parliament “as part of a progressive alliance that pursued progressive policies”.

Even leaving aside for a minute the fact that the SNP has not pursued any policies in Scotland of late, let alone progressive ones, it is hard to see the rationale behind Sturgeon’s gambit.

Perhaps her memory is short but just two years ago a similar ploy by her predecessor to prop up a minority Ed Miliband government had the unintended consequence of delivering David Cameron to Downing Street.

Voters south of the border were so alarmed at the thought of Scottish Nationalists helping to set the Westminster agenda that they gave the Tories an unexpected overall majority, albeit a small one.

An opinion poll after the 2015 general election revealed the possibility of a Labour-SNP pact was one of the main reasons behind Labour losing.

However, Tory posters of Miliband in a grinning Alex Salmond’s pocket now seem rather benign compared to today’s alternative: a grim faced Sturgeon pulling Corbyn’s puppet strings.

There will be sections of the English electorate who despise the Prime Minister enough to prefer any alternative. However, those who were thinking of voting for Corbyn are not going to be more likely to do so because of the SNP’s endorsement.

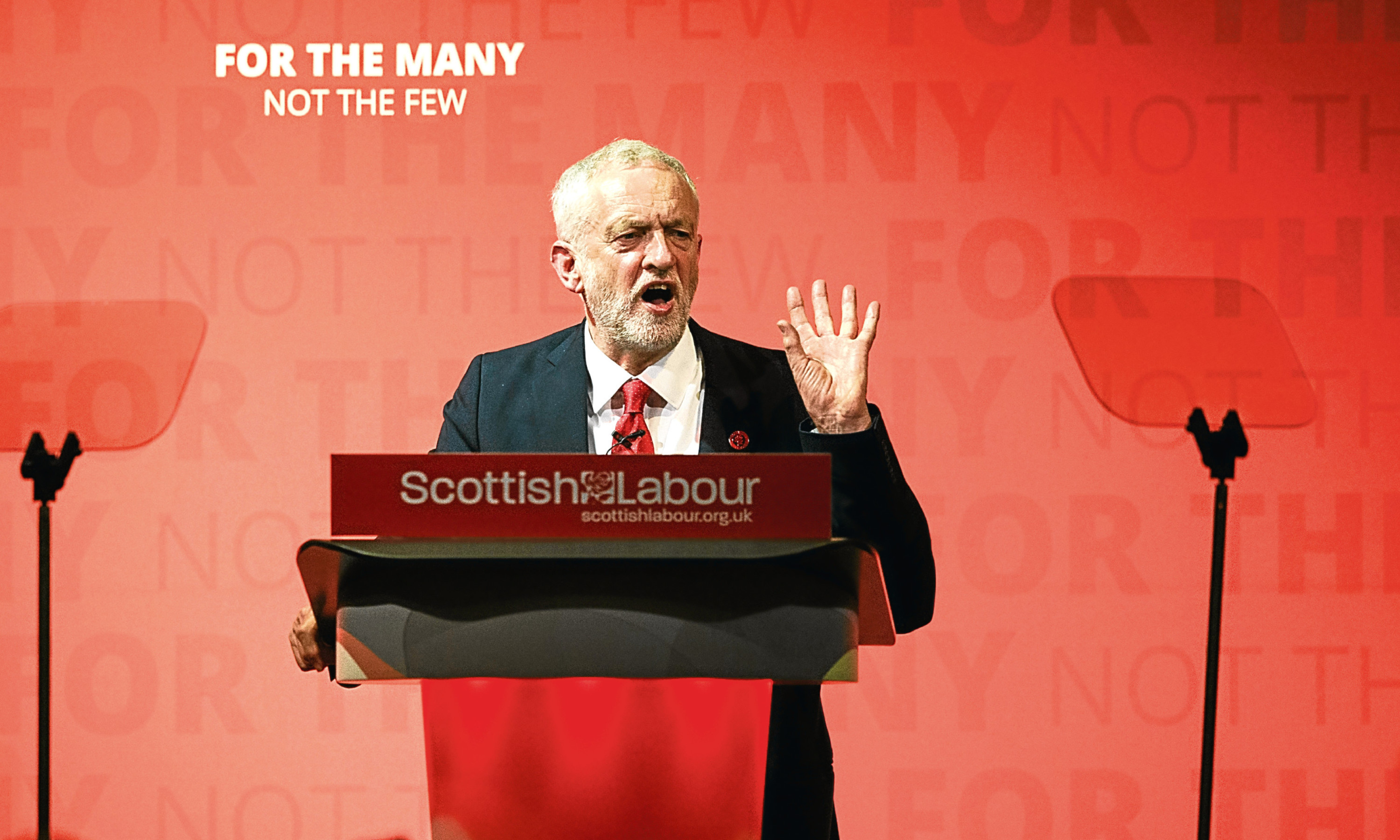

In fact, Corbyn himself has been quick to distance himself from the First Minister’s unwelcome overtures, which include a brazen anti-austerity pitch in her party manifesto, launched yesterday, to prove her Corbynite credentials.

He may well be emboldened by the weekend polls which showed the gap between him and Theresa May narrowing sharply since the start of the campaign.

And he may also have heard Sturgeon say that she thought he was not up to the job of PM, although she was still willing to help put him into government.

This is the kind of cynical contempt for the electorate we have grown accustomed to in Scotland but what are voters elsewhere to make of it?

Surely they too can see the Nationalists’ offer for what it is, an attempt to secure a second independence referendum for Scotland – which Corbyn said he is “absolutely fine” with – rather than a desire to craft progressive policies.

For undecided voters outside Scotland, the single issue SNP, which has added nothing to the good of the nation despite its noisy presence in the Commons, will be a major turn-off.

People who are, say, pro-Europe but uneasy about Corbyn are going to be less not more likely to vote for him if he comes in a package with the snarling Scottish separatists.

So does Sturgeon maybe think a Corbyn deal will encourage Scots to back her?

The most recent poll in Scotland will be deeply troubling to the Nationalists. It suggests they will lose more than half their 56 seats on June 8, with both the Tories and Labour gaining ground.

The Scottish Conservatives would win 17 seats if the SurveyMonkey analysis is right, while Labour would grab back 12.

Under Ruth Davidson, the Tories here have been rebuilding their voting base since the Scottish elections last year, when they destroyed the SNP’s Holyrood majority.

But the apparent Labour advance is more sudden. If Corbyn and his Scottish counterparts really are getting their message across after a long losing streak it will be at the SNP’s expense.

There can be no mileage for Sturgeon then in courting Corbyn and the measure backfired almost as soon as she mentioned it, with May herself mocking the match that the SNP leader said would “lock out” the Tories.

It is Sturgeon’s hatred of the London government that has clouded her judgment. Because she can’t see beyond her own emotional response to the Conservatives, she has misread her country’s mood since last June, when she tried to link the EU vote to a new independence ballot.

What’s more, she probably sees in Corbyn, for all his obvious limitations, something of a kindred spirit in his attitude to the United Kingdom.

While he may not be a Nationalist, he has throughout his political career protested against all British foreign policy, regardless of whether it was the Conservatives’ or Labour’s.

He is, like many on the far left, an anti-patriot, outspokenly opposed to the establishment at home but not necessarily in other lands.

Corbyn even managed to blame the Manchester bomb not on the extremist perpetrators but on British decisions abroad.

Sturgeon has found in Corbyn, whatever her political misgivings about him, someone almost as determined as she is to undermine Great Britain.