Kezia – a nice person in a terrible job doing OK. Not much of an epitaph but not bad, either.

She was Labour’s fifth leader since they lost power in Holyrood in 2007 and looked no more like getting back into office than Wendy Alexander, Iain Gray, Johann Lamont or Jim Murphy before her.

Kezia is as nice as John Swinney but without his good fortune to be in the right place at the right time – in the bonfire night of politics, they are sparklers rather than rockets.

She had only the dilettante’s interest in the bickering which binds politicians into parties.

Her sudden departure from the job of leading the Labour party in Scotland has surprised – nobody heard a rumour – and not. Who wouldn’t want out from such a wretched task?

Like a head girl lured into the underworld of what happens behind the bike shed who has finally fled for her sanity, Kezia is out.

Arguably, she was successful. Labour has gone from one MP to seven and while it has slipped to third in Holyrood, the party was on a decline that she was unlikely to reverse in two years.

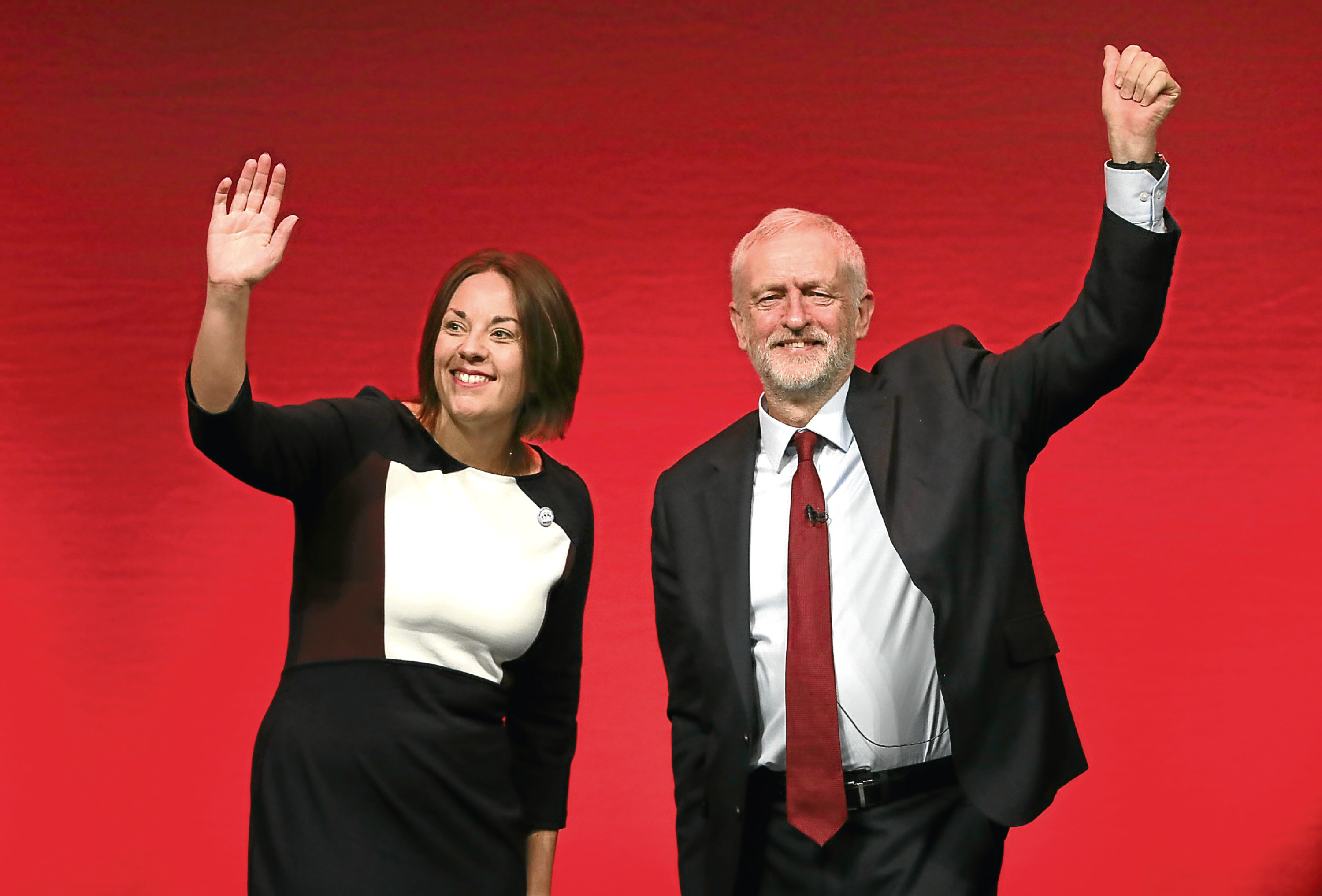

Depending on your view, Scottish Labour’s recovery in Westminster is either because Jeremy Corbyn is the messiah or voters were switching away from the SNP.

Kezia’s departure has all the marks of a sacrifice for the greater good, suggested by the left of the party who can’t bear Blairites like Dugdale.

By Blairite they mean centrist, affable people who aren’t particularly ideological.

As to whether a more left-wing man will do a better job, it is unlikely.

Corbyn’s anti-Europeanism, the persistent tales of anti-Semitism in London Labour, the sense of sexist old blokes hammering out old ideas… all give his leadership the stain of male self-satisfaction.

Men undermined Kezia – chiefly Neil Findlay and Alex Rowley, who briefed for the left. Both have said they won’t run for the top job.

Tweets are instead being pointed at Anas Sarwar, a rather bland man who, like his father, has had run-ins with the taxman – not ideal material for leadership when scrutiny of more private affairs is so often the achilles heel of politicians. The party’s problem is not mainly about personality but policy. It has very little to say beyond rallying cries against austerity.

Labour smells of the past, like the aroma from charity shop tweeds. A sentimental but unpleasant whiff of days gone by.

There are signs of change, but they are not enough.

The political issue of the day is Brexit, and Labour are slowly edging towards a soft position, allowing for continued membership of the Single Market.

This is good news for metropolitan liberals who want Labour to stand against Tory nationalists but a betrayal of those Labour voters in the north of England who like that they “took back control” over immigration.

As to economic policy, Corbyn’s vision amounts to spending a bit more.

Labour proposes marginal tax increases, but nothing of the depth or intent shown by Labour governments in the 1970s.

The challenge post-Brexit is far bigger than just a dose of infrastructure investment and easing off on welfare reform.

Britain has to invent a new set of laws and practices which make it competitive enough to survive outside the EU while still complying with most EU regulations in order to trade with the bloc.

Much as it may stick in the craw of Scottish Labour, the party is in a pretty similar boat to the SNP.

Both cling to the architecture of the post-1945 state while showing no sign of new thinking.

Simply banging on about the NHS is not enough, as the Scottish Government’s problem with waiting times, staff satisfaction and recruitment show.

While the right of politics is toying with old ideas about race and identity, the left is floundering.

The more Corbyn stays in office, the more his rhetorical repetitions and emphases ramble on but on the matter of serious critique of modern society he is silent.

If Labour really want to revive and take over from the SNP, then they need something deeper.

The malaise many voters feel is that government is an expensive, elaborate theatre for self-interested people which muddles the delivery of services to people and, broadly, the voters are right about this.

The trick of a new ‘‘people’s party’’ is to become useful again to people.

Of the five Scottish Labour leaders since Jack McConnell, only Johann Lamont began to think beyond the narrow business of party management to policy.

She was unfortunate enough to come up against the nats in their pomp, and her policy musings were shot down before they found an audience.

The new leader has to grapple with Scotland beyond the Yes and No of independence, with the fall-out from Brexit and with the wider crisis in western democracy.

None of what Anas Sarwar has shown so far suggests he is up to that challenge.

Lucky Kezia, who gets her life back. Unlucky Scotland, still waiting for some substance and political leadership.