The sex pest scandal that is engulfing Westminster has so far terminated the political careers of several Tories, including one cabinet minister and a chief whip, and a clutch of Labour MPs, and yesterday, tragically, it was connected to the death of the Welsh MP Carl Sargeant.

The Home Secretary, Amber Rudd, has said she would like to kick those guilty of sexual harassment out of parliament, despite the government’s slim majority. And Theresa May, the Prime Minister, perhaps in response, has reportedly put her party “on a state of readiness” to fight by-elections.

Meanwhile, in Scotland, the political community, or parts of it, is reeling from the realisation that this country is not so different, after all, and a couple of sleazebags have been unearthed at Holyrood.

This should surprise no one, human frailty not being a respecter of borders, but some MSPs had thought the Scottish parliament was immune to inappropriate behaviour because it lacked a drinking culture – an unlikely story, of course.

While on a different scale to that in London, the hospitality in Holyrood can be legendary, too, and some members, past and present, are a drinking culture all by themselves.

But that’s another column. What is unfolding, principally in Westminster, is troubling on many levels, not all of them related to sexual politics.

In years to come we might be able to study the events with better perspective and will probably conclude that the description “witch hunt” was apt.

For now, as almost every day brings a new revelation of mostly male lewdness, all we can do is try to distinguish between legitimate accusations of abuse and the ‘victims’ with dubious motive jumping on the bandwagon.

Unlike the Harvey Weinstein horror story, “pestminster”, as it has now been termed (to some in Edinburgh’s chagrin), is not straightforward. While Weinstein denies the more serious allegations against him, there is little doubt he preyed on women who were younger than him and less powerful.

Some Weinstein-like tales have emerged in British politics – the rape of the then-19-year-old Bex Bailey, a Labour National Executive Committee member, by a more senior party worker being one of them.

Harassment doesn’t have to go that far to be unacceptable, though, and there are plenty of charges by women against, typically, older men of a creepy, rather than criminal, nature.

Who would want to be the judge of which claims to act upon and which to dismiss? There are, as many commentators have already said, so many nuances in the minefield of human relationships.

But if a common rule had to be applied to sift through the categories of complaints, the obvious starting point would be simple: power.

What distinguishes one woman’s nightmare from another’s irritation over unwanted attention nearly always boils down to her ability to respond.

In most cases where women have been slow to report harassment – or have only come forward in the wake of a single, brave whistleblower – it is because they are afraid of the consequences. In Westminster, as on Weinstein’s casting couch, these consequences are professional.

Any victimised woman who has been silenced in the past by fear of losing her job, or her reputation, will be cheering now as one pest after another is publicly humiliated and sacked.

But remove power from the equation and are we not left with the boorish maybe, or possibly the bumbling, and (to be really charitable) occasionally just the misunderstood specimens of daily adult interaction?

Julia Hartley-Brewer, the journalist who first exposed Defence Minister Michael Fallon’s penchant for female knees, was in her own words most definitely not a victim. Mr Fallon had no power over her and she dealt with him accordingly.

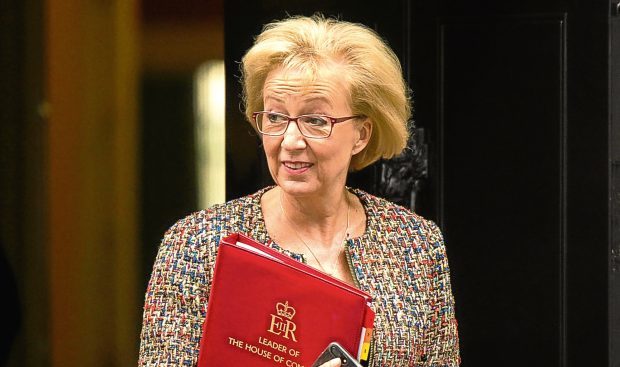

Andrea Leadsom, the Commons Leader, though, was apparently instrumental in engineering Mr Fallon’s downfall over saucy (apologies for the word but that’s all they were) remarks he once made about where she could warm her cold hands.

Mrs Leadsom has since said that ministers who make women “feel uncomfortable” could face the sack. In a couple of weeks, the plight of a defenceless teenager at a party

conference is being discussed in the same context as the perceived discomfort of one of the most high-profile women in politics.

There is evidently a need to correct a culture that allows the powerful to pounce on the weak, and Theresa May announced on Monday a new grievance procedure to deliver

justice to victims, regardless of the party apparatus. This won’t stop people behaving badly but it might bring the worst culprits to light more quickly.

And to ensure the real victims are not forgotten in the hysteria, those who are able to stand up for themselves –and this can include young women too – must seize the day.

Learning to navigate the spectrum of male misconduct, especially at work, is an essential skill – and an empowering one.