Escaping from the winter weather, I took Inka for a walk in the shelter of the woods beside Capo Quarry, lying just off the Lang Stracht, the long, straight road running from the Upper Northwaterbridge to the foot of the Glenesk road. The woods are criss-crossed with roe deer tracks and there’s plenty of interest for dogs.

A sharp crack caught my attention and from the corner of my eye I saw a tree fall to the ground. Being me, I had to investigate!

An old pine trunk whose top half had snapped off in some long-forgotten gale lay on the ground. Scattered round the base were fragments of rotten wood. If I hadn’t looked closer I might have assumed it had finally surrendered to the ravages of old age and the elements.

I noticed that the core of the tree had been cleanly sawn through with a bush saw – for there had been no sound of a chainsaw. There was no sign of the intrepid lumberjack, just a whiff of guilt hanging on the air. The vanishing woodsman could have spared himself a crise de conscience for I wasn’t going to lecture him for taking what I would call nature’s bounty and which had no better use than to be chopped up and burnt in his wood-burning stove.

But the tinder-dry, rotten wood gave me the idea of resurrecting the stoorer I made for grandson James some 15 years ago.

Take an empty Lyle’s Golden Syrup tin and bash a number of holes in the sides with a wide-bladed screwdriver or something similar. Thread a piece of stiff wire, about 30 inches long, through two holes opposite each other at the top of the tin to form a handle.

Scrunch up small balls of paper into the bottom of the tin. Fill the tin with the tinder wood and put the lid on tightly. Light the paper through a hole at the foot of the tin and blow through the holes until the wood begins to smoulder and the stoorer begins to smoke. Then wander round the garden, swinging the stoorer round your head, until the wood has burnt up and the stoor stops smoking. Don’t forget that the tin gets hot.

And what’s the object of this ploy? In my case it was to keep a grandson entertained, but a member of the audience at a talk I gave suggested the idea might have originated as a practical countryman’s beekeeping smoker, which would have been cheaper than buying a custom-made one.

A member of the audience at another talk, given in Fife, told me that he grew up in the mining village of Rosie between Buckhaven and East Wemyss – the Rosie pit is long closed and the village has been absorbed into East Wemyss. But the village youngsters filled their stoorers with chips of coal and warmed their hands at them in winter.

Pigeon post

From the number of preened feathers clinging to branches, it was clear that the Capo woods have been a favourite roost for the pigeons over the winter. At about three o’clock they began to fly in and the woods resounded to their constant cooing, three long tones followed by two short – coo-coo-coo-co-co.

They will have been feeding hard all day to maintain body heat throughout the night, but the dense spruce foliage provides extra protection from chill winds. Once a roosting pigeon has fluffed up its feathers to create an insulating layer of warm air, it will survive a considerable drop in temperature overnight.

There are social benefits, too. Roosting in numbers creates a sense of safety in numbers, and it seems generally accepted that there is an information exchange of where the best feeding sites are so that pigeons which have had poor pickings one day can join the feeding parties of more successful birds on the next.

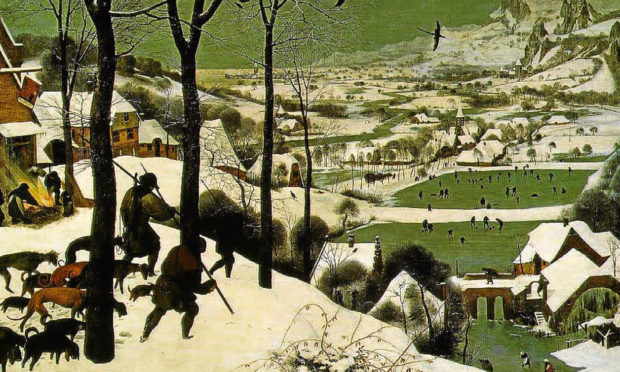

Dram good curling

Monday’s edition of this paper had a page of photographs of curling outdoors – as the ‘roarin’ game’ originated – going back to 1959. They brought back a memory that still makes me smile.

The Doyenne and I both played for Dun Curling Club, the name reflecting its association with House of Dun and Duns Dish, the shallow loch lying to the north of the house. More than 40 years ago the Dish froze hard enough to hold an outdoor bonspiel (curling match).

Two carloads of curlers came down from Stonehaven, accompanied by the non-playing father of one of the drivers. The father visited all the rinks throughout the afternoon, so much enjoying the hospitality of the ‘brotherhood of the ice’ that he finally sat down beneath a tree and fell sound asleep.

When the bonspiel finished the curlers from Stonehaven drove home, each assuming the father was in the other car.

The father awoke to the curler’s worst nightmare – the whisky was gone, he was alone and it was dark. The son got home to the horror of having abandoned his father. An anxious dash back to Duns Dish and, happily, father and son were quickly reunited.