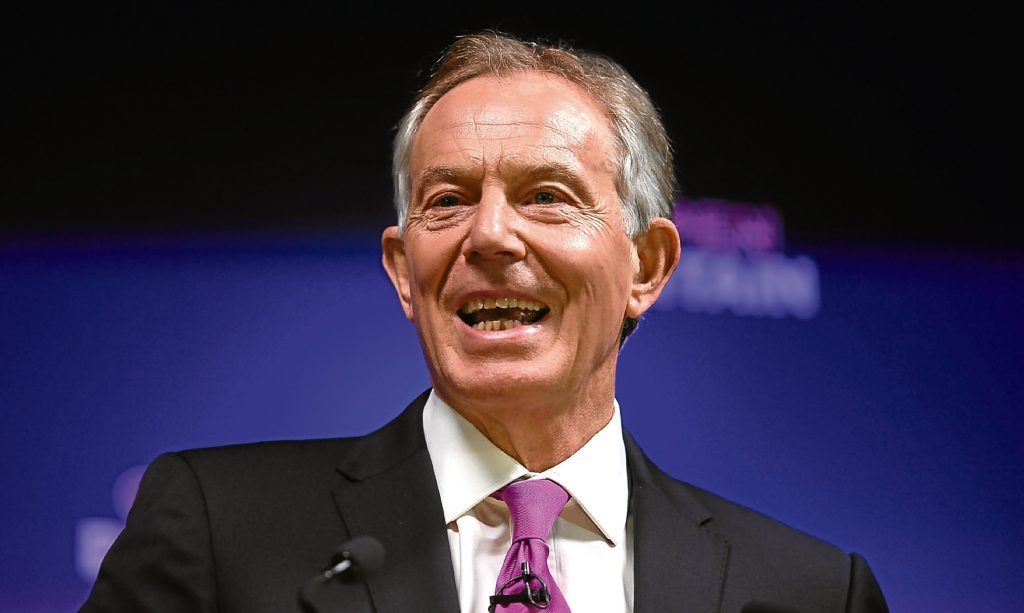

Where has Tony Blair been for the past two or three years? Clearly not in Scotland because he doesn’t have a clue what people here are thinking.

In an interview with Holyrood magazine, the former Labour prime minister said it seemed “absolutely bloody obvious” to him that if Scots, who voted to stay in Europe, were wrenched out by Brexit then that would help the independence movement.

“It doesn’t mean to say I agree with it, but it’s bound to have an impact.”

That is exactly what Nicola Sturgeon thought in 2016 following the UK’s decision to leave the EU and Scotland’s vote, by 62% to 38%, to remain.

So convinced was the first minister that the result would turn unionists into nationalists overnight that she based her entire subsequent independence campaign on Europe.

This, as we now know, ignored basic facts. One was that half a million separatists wanted out of Europe because they regarded being bound to Brussels with the same distaste they felt about being bound to Britain.

Brexit, instead of uniting Yes and No voters, has split the nationalist camp and weakened the leadership of Sturgeon. And the Brexit bounce among unionists that she banked on has failed to materialise, even as the process of leaving has brought out the very worst in UK politics.

The British Social Attitudes Survey last year found the SNP suffered a drop of 15% among Eurosceptics during 2017’s snap general election, when the party lost a third of its seats.

And a Panelbase survey last year, conducted nearly two years after the Brexit vote, showed the ranks of No voters had swelled to 57% (compared to 55.3% in the 2014 referendum), while 43% favoured secession. Support for independence has stayed around 45% since then.

It is bad enough Blair has become so blinkered over Europe that the Scottish dimension in British political life, which he once understood (he ushered in devolution remember), is now vague to him.

But for Sturgeon to so badly misread the mood here is more alarming, considering she is supposed to be representing our interests.

Both politicians have other agendas of course. Blair’s is to stop Brexit happening, which he imagines he can do by helping to orchestrate a second EU referendum.

He would sooner Scotland did break away from the UK in protest, than go along with the democratic will of the rest of Britain.

And Sturgeon only wants one thing. Europe is a means, or she still clings to the idea that it is, to achieve independence, and she shows no sign of altering course from that misguided position.

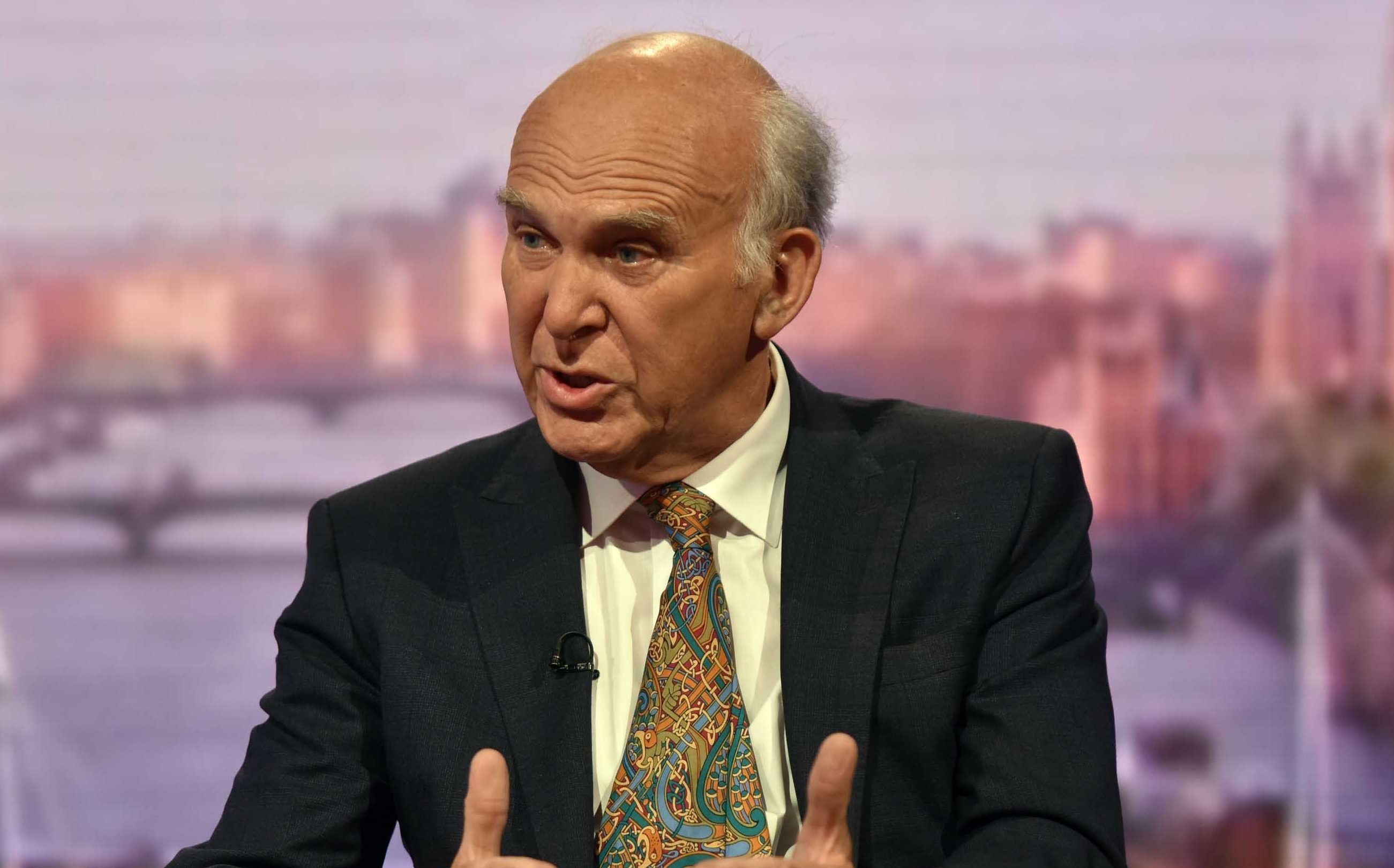

So we must welcome the wiser voice of the Lib Dem leader, Vince Cable, who said that Brexit has made Scotland less, not more, likely to back a Yes vote.

The SNP deputy leader, Keith Brown, in a speech in Aberdeen on Saturday, insisted that independence would be the opposite of Brexit, and Scots were ready to listen to the nationalists’ case as a result of the meltdown south of the border.

But Cable, in Scotland over the weekend for his party’s spring conference, rejected the claims, arguing that independence would be even more disruptive than Brexit.

“In a way, I would have thought the dynamic was in the opposite direction,” he said.

“When you see the chaos and upheaval that has been created by trying to leave the European Union with which we have very strong ties, but not overwhelming, the fact that business has just stopped investing.

“The consequences of breaking up the UK, which is much more tightly integrated than we are with Europe, would be even bigger and I suspect that not too many people in Scotland would be entranced with the idea of piling on more uncertainty and disruption than they’re getting at the moment.”

Cable wants what Blair wants, a People’s Vote to try to undo Brexit, but he has not allowed his opinion to completely cloud his judgment.

The events of the past week, with MPs splintering from the main parties in Westminster, have yet to be reflected in an opinion poll in Scotland, but culturally this country is aligned with Britain (something else Blair gets wrong) and the majority inhabit a moderate mindset.

The hostilities of Brexit will surely drive all but the zealots towards calm consensus, not further fighting. If Britain, not just the House of Commons, was voting on Theresa May’s deal, she would have had it in the bag long ago.

The same sense will prevail over independence. Apart from the fervent few, people will yearn for an outbreak of peace in the wake of so many years of bitterness. This is not the time to divide the nation again.