Part One: The Situation

There is an old French saying that roughly translates as beauty is pain.

But bruising, nerve damage and blindness are more than just a little bit of suffering.

All three are common complaints from victims of botched Botox and dermal filler procedures. And complaints over bungled procedures have skyrocketed in the UK; more than quadrupling from 378 complaints in 2017 to 1,617 complaints in 2019.

That number is predicted to rise once again in 2020, as thousands of women – and more than a few men – queue up to have their faces pierced and prodded with needles in pursuit of perfection.

For entrepreneurial individuals there is serious money to be made here, and premises are springing up on every corner offering plumped pouts and smooth foreheads for competitive prices.

There are no regulations covering these injectable treatments, meaning they can be administered by anyone, anywhere.

Lawyers in Dundee and Aberdeen are seeing their books fill up with victims of botched procedures looking for compensation.

But with no laws in place surrounding this flourishing side of the cosmetics industry, complaints often hit a brick wall and disreputable practitioners shrug their shoulders and live to inject another day.

Progress on tightening the rules has been painfully slow, but earlier this year the Scottish Government revealed its intention to become the first in the UK to crackdown on these “wild west” cosmetic procedures.

So as coronavirus raged through Asia in January, back here in Scotland the government released a consultation paper which proposed an overhaul to the system.

But nothing is set in stone yet, and even without a global pandemic it’s likely to be sometime before any headway is made.

In the meantime, salons, clinics and spare bedrooms are all set to reopen for business, readying themselves for an expected boom in requests for fillers and Botox from clients who have spent the last three months cooped up inside with only social media and a mirror for company.

Part Two: The Numbers

The most recent reports estimate that the non-surgical cosmetics industry in the UK is worth more than £3.6 billion, with injectable treatments such as Botox and fillers accounting for nine out of 10 procedures.

Unlike the traditional plastic surgery market, which has found itself stagnant over the last few years, non-surgical cosmetic treatments are now viewed as an integral part of beauty regimes across the country, offering a fast and relatively inexpensive “fix”.

In some cases, an injectable treatment costs no more than a high-end face cream and can achieve noticeable results, making it an attractive prospect.

Thanks to the lack of regulations and many thousands of unregistered practitioners offering these injectable treatments, it’s impossible to gauge exactly how many women, and increasingly men too, are choosing to go under the needle.

What we can measure however, is when it goes wrong.

Save Face is a voluntary national register of accredited practitioners who provide non-surgical cosmetic treatments.

The organisation has seen the number of official complaints about procedures gone wrong rocket in recent years.

Dermal filler complaints make up the majority of the statistics. In the last year alone, complaints regarding this treatment have more than doubled.

Many of the complainants suffered from serious injuries as a result of fillers being improperly administered, from severely swollen lips and anaphylactic shock to blindness and necrosis, which is when tissue in the body dies due to lack of blood supply.

Of course these are only the procedures which were reported. It’s thought that there are many other hundreds of cases in which patients were unhappy with their results but were either too embarrassed to report it or unsure how to do so.

Even if you do report a botched procedure there is no guarantee of resolution, as personal injury lawyer Jennifer Watson knows very well.

Working from her office in Dundee, Jennifer specialises in bungled beauty treatments of all kinds, from brow tints and bad haircuts to laser tattoo removal and facial injectables.

In the 12 years she’s worked at her current firm, Digby Brown, Jennifer’s seen all manner of gruesome and even life-threatening injuries caused by the negligence of hair and beauty therapists across Scotland.

“It all came about when a couple of cases involving laser hair removal happened to pass my way – quite frankly because no one else in the office knew anything about laser hair removal, and they were passed to me because, well,” she shrugged and smiled, “I was the only one who even knew what it was.”

From those first few cases which landed on her lap more than a decade ago, Jennifer has seen her case load balloon from five or six botched beauty lawsuits per year to approximately 200.

Aware of the rapidly growing industry and its increasingly slapdash nature, the Scottish Government offered a faint glimmer of hope back in 2016.

A three-phased approach was planned to require anyone administering injectable treatments, such as fillers or Botox, to be officially registered with an organisation called Health Improvement Scotland (HIS) before legally being allowed to practice.

Phase one was implemented smoothly, meaning that anyone with medical training who is injecting Botox and filler is part of a legal database of accredited practitioners.

“Unfortunately they are not at the stage of implementing phases two and three yet,” said Jennifer derisively, “and they are the two phases which concern me the most.”

“These practitioners are not medically qualified, they haven’t got experience and often haven’t gone through the appropriate training or qualifications.

“Non-surgical cosmetic treatments are very, very dangerous and have far reaching implications if they go wrong.

“Very often (practitioners) go on a two-day course to learn how to inject filler and if you get that wrong, the individual can be left scarred for life.”

“Some people have never even been on a course, and they advertise on Facebook or the like where potential clients don’t question the practitioner’s qualifications.

“I am really worried that there is going to be a massive boom after lockdown of people going to get beauty treatments – whether it’s getting their hair cut and coloured or getting their Botox topped up – and that people will not do the proper background checks on their practitioners.”

Part Three: The Search For A New Face

Save Face estimate that more than 80 per cent of complaints reported to the organisation are about treatments carried out by lay people, including hairdressers and beauticians.

They advertise their services online, and social media is key.

Glossy “before and after” pictures are commonplace, featuring formerly unhappy women with thin lips and no confidence who are transformed after a 30-minute appointment with a syringe full of filler.

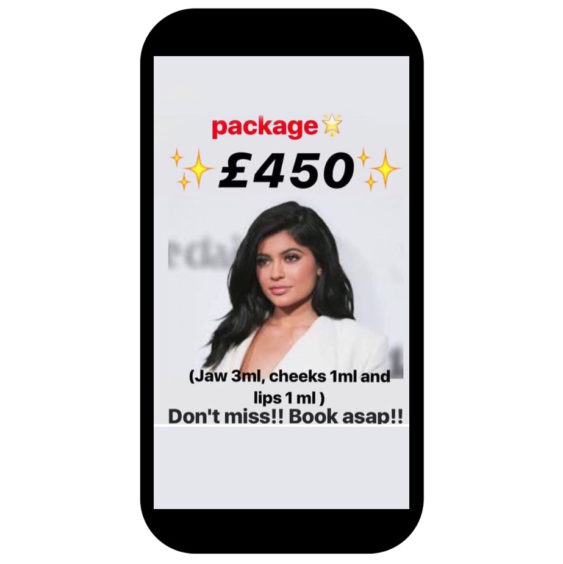

Pictures of glammed-up celebs from the likes of Love Island and The Only Way is Essex pepper social feeds, while package deals often called “The Kim K” and “The Kylie” – named after Kim Kardashian and Kylie Jenner – sweeten the deal.

Hashtags are another popular way to find practitioners, particularly on Instagram. With tags like #lipfiller often followed by aspirational terms like #luciouslips and #femaleboss.

However, as easy as it is to find someone to inject you, when things go wrong many victims find themselves very much alone.

Even if you have been left permanently disfigured there is little chance of recompense, and this is down to one major stumbling block: insurance.

If the salon or practitioner involved does not have sufficient insurance – and anecdotal evidence suggests that most unaccredited businesses don’t – then pursuers can kiss goodbye to justice being served.

Having insurance isn’t mandatory so practitioners aren’t breaking the law by foregoing it, explains Caroline Kelly, a solicitor at Thorntons law firm in Dundee who specialises in clinical negligence.

“It can even be as simple as a hair salon renting a chair to a beautician. Legally this doesn’t require public liability insurance,” she said.

“When you approach the salon to tell them something has gone wrong, you either don’t get any response or they say the person who did [the treatment] only rented the chair and doesn’t work there anymore.

We live in a society where a young girl of 23 feels that she needs Botox and I hate that.”

Caroline Kelly

“From there it is up to you to try and find this person which can be very difficult.

“It might turn out that they do have insurance, but it doesn’t cover them for the procedures they are carrying out, or that it’s been voided because they haven’t followed correct procedure.

“It’s a big problem because ultimately if they don’t have insurance, then unless the practitioner has personal funds you’re going to struggle to get any compensation.”

Of course receiving a few quid in the bank does not make up for the often horrendous experience of a botched beauty procedure.

The physical and psychological trauma can take months, if not years, to heal. But, as Caroline points out, some monetary compensation can at least help correct mistakes to get your life (and face) back to normal.

“We live in a society where a young girl of 23 feels that she needs Botox and I hate that,” Caroline said. “But if they want to do it they should be able to do it safely and with the option of compensation if anything goes wrong.”

With both her caseload and list of concerns growing, Caroline was pleased to finally see the Scottish Government returning to the issue of regulating the cosmetics industry earlier this year.

It appears that phases two and three (requiring non-medical practitioners to register with HIS) of the initial 2016 plan have fallen by the wayside.

Instead, the government released a consultation paper seeking views from the public on the “regulation of non-medically trained providers of non-surgical cosmetic procedures”.

In the document the government acknowledged the “growing risks” associated with the industry, and the increasing number of unregulated premises as their top concern.

Together with a group of like-minded lawyers, Caroline responded to the consultation by stating that the current situation cannot be allowed to continue.

Though thoroughly supportive of change, she urged the government to think bigger.

“My view is that ultimately the proposals don’t go far enough in terms of regulation,” she said.

“It’s only looking at procedures which pierce or penetrate the skin in some way, so treatments involving lasers and dermaplaning (where a scalpel is scraped over the face to remove hair and skin cells) are still excluded.

“I appreciate they are focusing on the higher-risk parts of the industry first, and that is important, but I can only hope they will eventually get to the point of regulating the rest of it too.

“It’s a huge undertaking, and while many lawyers think it should be the ultimate aim, whether the Scottish Government will get to that, well… I don’t know.”

Part Four: The Rise of the Instagram Face

When Botox first arrived in the UK in the early 1990s, we were living in a simpler time.

Nails were short, eyebrows were over-plucked and skincare uncomplicated. There were no smart phones. No one knew what a selfie was.

And Botox was considered to be something serious, like a facelift or a boob job.

But that was then. Today, teenagers as young as 13 keep regular salon appointments to ensure they always have immaculately manicured nails and on-fleek eyebrows.

The combined influence of reality TV, Instagram and self-promoting celebrities has led to a new aesthetic for the Instagram generation.

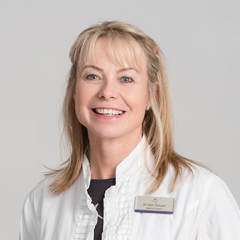

“There is a certain look that young people are going for,” said Dr Sam Robson, medical director at Temple Clinic in Aberdeen.

She has seen first-hand a dramatic uptick in clients coming to see her for Botox and filler injections. They’re looking for full lips, wide eyes, smooth skin and a straight nose. Plus the body to match.

“People take in photos of what they want to look like,” she said, “It’s my pet dread.

“It tends to be the Instagram influencers [that clients want to emulate], people want to look like Kylie Jenner and her friends, and they are scrolling on their phones as they’re talking to me.”

It’s virtually impossible to look at the rise of injectable treatments without coming across Kylie Jenner, the youngest Kardashian sister.

To an outsider, it seems improbable that the youngest member of this obscure American family, whose reasons for being famous no one quite seems to know, might influence young men and women in our own lives to consider going under the needle.

But in fact the meteoric rise of this controversial socialite family appears to correspond almost exactly with a boom in Botox and lip filler procedures, and Kylie is at the centre of it all.

After initially insisting her increasingly large pout was all down to good make-up, the youngest member of the Kardashian clan (then 17 years old) was eventually outed by her older sister Khloe as having had lip fillers.

In the 24 hours following the confession, UK clinics offering the same procedure saw a 70% increase in requests for the same procedure.

That was back in 2015, and since then the demand for facial injectables has rocketed.

In the UK there is no legal age limit for these treatments, and the procedures have become increasingly popular with young people around Kylie’s age.

Kylie herself later revealed she was only 15 when she began her journey under the needle after a boy commented on her small lips.

Since then she has produced a best-selling lipstick and liner range, and amassed a colossal 178 million Instagram followers.

For Generation Z, who spend much of their lives online, being permanently selfie-ready is more than just a full face of makeup and a duck pout.

You must be utterly flawless, “like a Disney princess” suggests Sam, at all times.

If you’re older, the desired look is different, and harder to spot.

“Once people are over the age of 30 to 35 they tend to have different expectations,” said Sam.

“They are usually more concerned with wanting to regain something they had before, and – most importantly – they want to look natural, not like they’ve had heaps of work done.”

Smooth and youthful skin is the order of the day, along with a taut neck, full lips and more defined cheekbones.

“They want reassurance that they’re not going to look like those celebrities or people you see on social media.”

Sam herself comes from a medical background. For 17 years she worked as a fully qualified GP before making the leap into aesthetics in 2011.

She explains that her first foray into the world of injectables was an accident, after a friend was unable to attend a Botox training course in London and suggested Sam go in her place last-minute.

“I knew nothing about Botox,” Sam said, “but I thought the course was absolutely fascinating. That was at a time when it was just doctors and nurses doing the treatments, of course.”

If someone is asking me for a TOWIE look (copying the stars from reality show The Only Way Is Essex), I have to tactfully say that I’m not the right practitioner for them.”

Dr Sam Robson

Things are rather different today, where anyone who can get their hands on the products is free to administer them.

“You can buy it all online,” said Sam. The needles, the filler, even the professional-looking white apron.

“But who knows what you’re really buying. There are 160 dermal filler products approved for use in Europe but most reputable practitioners wouldn’t touch the majority of those.

“The good stuff is expensive, so if someone is offering you a really cheap filler treatment, who knows what they’re injecting.”

Botox is slightly different. As a prescription-only medicine, it can only be issued by a medical provider. The loophole however, is that this medical provider does not need to be the one administering it.

Practitioners can set up their “clinic” with no legal requirement for insurance, regulation or even a proper premises.

So you could set up in your spare room? “Yes,” says Sam. “Or your garage. It does happen.”

Training to inject Botox and fillers is technically not mandatory either, merely “recommended”.

Mostly this takes the form of a day or week-long course depending on the level of education desired.

However, some courses can be done entirely online, where Sam points outs that trainees will receive a certificate of completion without ever having injected anybody.

“Coming from a medical background, I was very naïve to not realise that this could happen,” she said.

“If someone is asking me for a TOWIE look (copying the stars from reality show The Only Way Is Essex), I have to tactfully say that I’m not the right practitioner for them.” said Sam.

“Maybe it sounds a bit grandiose, but I have to feel that I’m doing the right thing for my patients. That is something which is drummed into you at medical school.”

She says that reputable practitioners will refuse to over-fill a patient’s face, but – considering there are plenty of disreputable ones who have no such qualms – is fearful that the long-term consequences of filler overuse will be seen in the faces of Kardashian acolytes in the decades to come.

“You see people with their lips overfilled, and they do shrink back down again, but then they go and do it again and again and again,” she says. “We don’t know what the long-term effects are, because your tissue stretches and people lose perspective of what looks attractive or natural.

“They (disreputable clinics and practitioners) are motivated solely by financial gain, and are not likely to be acting in the interest of the patient.

“They think, ‘oh this is a good way to make easy money’, and I think no, it’s not.

“You shouldn’t be playing on people’s insecurities like this, and just because it’s legal, doesn’t mean it’s safe.”

Part Five: The Beauty Trap

Picture-perfect skin and sculpted, contoured cheekbones, wide almond-shaped eyes which taper up into a feline point, and that full, inescapable mouth.

This look is what Twiggy’s lashes were to the 1960s and what Kate Moss’ dewy skin was to the 1990s.

Without Instagram, of course, this specific look of the 2020s might not exist.

The social network, which first launched 10 years ago, has helped popularise and normalise the look among a generation of young women.

It’s aspirational, and in the same way that magazines have long edited photos of celebrities to smooth out imperfections, Instagram users can do the same to themselves with just a few taps.

With apps like Facetune to help, it’s easy to get used to seeing yourself with a perfect jawline and full luscious lips. Suddenly making the leap from online filters to real-life fillers doesn’t seem like a huge jump.

As soon as I turned 18 I was really keen to try out something a bit different and out of my comfort zone.”

Karla Sinclair

Originally from the small farming town of Turriff in the north-east, Karla Sinclair moved to Aberdeen two years ago.

The now 19-year-old can’t remember what motivated her to first get fillers – it was more of a gradual decision; people she followed kept coming up on her newsfeed with new lips, or noses, or cheeks, meanwhile several close friends went under the needle themselves and encouraged her to go for it.

“As soon as I turned 18 I was really keen to try out something a bit different and out of my comfort zone.”

“After hearing such great feedback from friends who had underwent the procedure in the past, I decided to try out lip injections for myself.”

When it came to choosing a practitioner, Karla had heard good things about a new place which had recently opened up near her family home.

“I did a bit of research and all her reviews were extremely positive,” she said, “so I messaged her on Facebook and she was lovely from the outset.”

Karla started out with 0.5ml in the syringe, which is the amount recommended for first timers.

“To keep the look up I had to visit the clinic at least once a month for the first three months,” she said.

“From that point, it was closer to once every two or three months for a more ‘full’ appearance.”

Karla has never strayed above 1ml of filler per session, but those after a really full-on pout can get up to 2ml per session.

When Karla debuted her new look to friends, they were impressed with the results.

“My friends absolutely loved them,” she said. “A number of them went on to contact the same practitioner and try out the procedure for themselves.”

Her family, meanwhile, were less pleased.

“Like all parents, my mum and dad didn’t see the need for me to have any procedures,” she smiled.

“They were both incredibly concerned about the cost, as well as the mishaps that can occur when procedures like lip fillers go wrong.”

Karla says she doesn’t feel pressure to use fillers to achieve a certain look, but understands why other women might feel pressure alter their appearance.

After all, she too loved the look the fillers gave her.

But following a year of regular treatments, Karla decided to stop her appointments in February.

“I think it’s fair to say my parents were over the moon when I decided to throw the towel in and stop topping my lips up,” she said.

“I loved receiving the treatments, but the cost – roughly £150 per treatment – started to make me consider whether or not the regular procedures were really worth it.

“After all, I’ve never lacked confidence or been brought to tears by my appearance.

“I think the filler has now pretty much completely dissolved from my lips and they’re back to their normal, small selves.”

For Karla, it seemed that lip fillers were just another teenage whim; and certainly nothing to be demonised.

It’s a reminder that Botox and lip fillers sit on a spectrum.

On the shelves of bathroom cabinets in homes around Scotland are many products whose sole aim is to change your appearance.

Stinging lip gloss designed to swell your lips; hair dye to cover stray greys; contouring pallets to change the shape of your face and many millions of creams and serums that claim to take years off.

As fat freezing grows in popularity and machines which can electric shock your abs into a six-pack fly off the shelves, nothing seems too far-fetched.

Perhaps injectables are just the latest fad in our never-ending quest for beauty, whatever that may be – online or off.