I’d never felt particularly Scottish until the day my boyfriend told me to “stop being such a peelie-wally”.

Despite having lived in Aberdeen his whole life, he clearly didn’t have a clue what he’d just said.

“You can’t be a peelie-wally,” I’d replied, “you’re either peelie-wally or you’re not.”

I suppose it’s not his fault that his Scots grammar isn’t what it should be; his parents are English and Polish, and he did go to a “posh” school after all.

“What do you think peelie-wally means?” I asked.

“I dunno,” he said. “A bit flaky? Like when someone bails on plans.”

I was incredulous. Growing up in a Scots household, I hadn’t even realised that peelie-wally wasn’t a phrase that everyone would know.

“How about baffies?” I asked. “Or oxsters? Bosie?”

He looked blank.

I, meanwhile, was mystified that these common words seemed like a foreign language to him.

But for him, and many other folk, Scots is indeed another language.

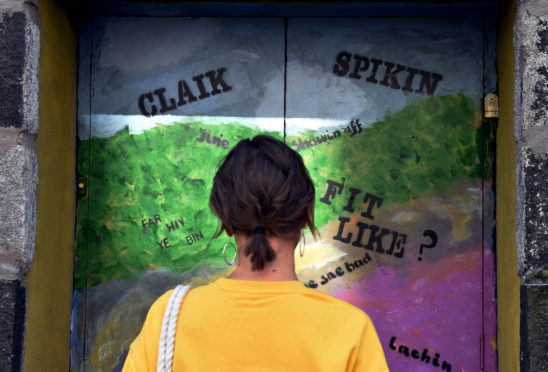

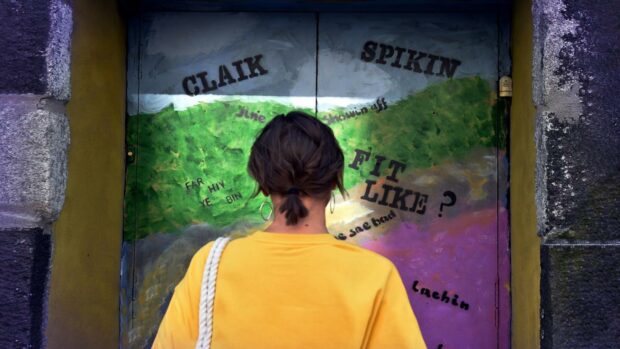

‘Spikkin proper’

In fact it’s recognised as the largest minority language in the UK, despite it not being officially learned, taught or standardised in any way.

A conservative estimate puts speaker numbers at around 1.5 million, spread across the length and breadth of the country.

But despite it being the mother tongue for many, the Scots language is struggling for recognition.

Dismissed by some as nothing more than a slovenly version of its sister tongue, English, there are worries that Scots speakers are turning their backs on a language which has existed for centuries years in favour of “spikkin proper”. Or in other words, speaking English.

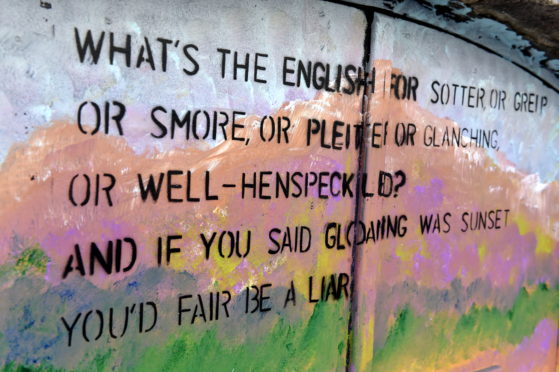

But when a languages dies out, more is lost than some funny-sounding words which end up on a tea towel for tourists.

A link to the past disappears and as the last speakers of a language die, culture and perspective dies with them, along with a sense of identity.

We lose the ability to describe ourselves; to tell someone what the weather is like (dreich, thanks for asking) or how you’re doing (I’m just chavin’ awa).

You can be scunnert rather than just fed-up, or havering rather than talking rubbish.

For many, Scots is an unlikely language of love. The language of the town and the folk you care most about.

But grimmest predictions have 90 percent of the world’s languages dying out by the end of this century, and Scots is one of those at risk.

Fit is Scots onywiy?

What is Scots anyway?

One of the biggest stumbling blocks facing Scots is that no one can agree exactly what it is, least of all those who speak it.

Some claim it’s a language, others think it’s a dialect. The rest probably think you’re confusing it with Gaelic. What most people don’t know is that Scots is officially recognised as an indigenous language of Scotland in its own right, and includes everything from Doric and Dundonian to Mearns, Orcadian, Glaswegian and everything in between.

Scots has also made it onto an exclusive list recognising regional and minority languages of Europe, and is classed as a “vulnerable” language by Unesco.

There are even calls for Scots language courses to be made available on Duolingo, the world’s biggest language learning app.

It seems that the only people who don’t believe it’s a language are the speakers themselves.

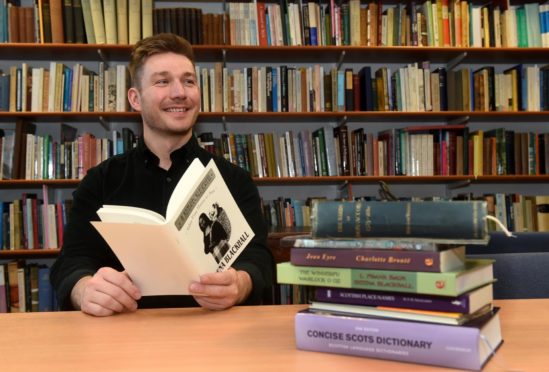

“The Scots have kent that they’ve had a language for the last 600 years, it’s only in the last 40 that they’ve forgotten it,” said Alistair Heather, a Scots writer and TV presenter hailing from Angus.

The 30-year-old is currently on a one-man mission to encourage Scots to reclaim their native tongue, and has been getting to the bottom of where the problems started.

“It’s unusual in Scottish history that folk arenae aware of what language they speak,” he said, “and it’s a bit of a minter (meaning: embarrassed or ashamed).”

“Linguists have never questioned if it’s a language, artists and writers have never questioned if it’s a language, and educators at the highest level have never questioned it. It’s just that we’ve got ourselves in a total fankle (tangle/mess) about Scottish stuff not being considered valuable.

“Over time Scottish history became a minor part of British history, Scottish literature became a very minor part of English literature, and Scots language by the same process, became seen as a minor part of the English language.

“The English didnae de that tae us,” he clarifies, “we did that tae ourselves.”

And Alistair has the perfect anecdote taken straight from his own life to illustrate.

…it was seen as working class to be speaking Scots, or that you werenae educated.”

Alistair Heather

Fresh out of school he found himself working in a call centre in Dundee, and was mystified to see the call handers policing each other’s speech.

“They’d say ‘dinnae speak oary!’ (common), even though it was just Dundee folk speaking to other Dundee folk at the end of the telephone.

“But we were self-policing because we had been telt oor language isnae right, it was seen as working class to be speaking Scots, or that you werenae educated.”

This stereotype persists today. English is seen as a superior, meanwhile Scots remains the butt of the joke and, for some, the language of teuchters (someone who lives in rural countryside).

Gradually this has placed an indescribable feeling of inferiority over the population. How good a person can you really be, and how good can your home be, if you don’t even speak correctly?

As a result, almost all native Scots speakers have learned to switch between Scots and English at the drop of a hat.

“Loads of cultures round the world have these partially-submerged languages that can only be used in certain spheres,” Alistair said.

“So Scots we ken (know) is a hame (home) language, it’s for your family, your pals, your freens (friends), it’s no really a business language.

“It means it’s cringy to hear it in some circumstances, like if a newsreader started speaking briad Scots, because we’ve got all this cultural training that Scots isnae good enough for that kind of sphere.

“It feels like a real clanger, a social faux pas, to use it in the wrong situation.”

But the only ones ever cringing were us. The term “Scottish cringe” even has its own Wikipedia entry as a result.

Trying to convince Scots to be proud of their native language isn’t something which can happen overnight.

While Scots language activists like Billy Kay have been campaigning for years for more recognition of the language, Alistair himself is taking a more ground up approach.

Alongside writing articles and appearing on TV documentaries, Alistair has also made numerous visits to HMP & YOI Grampian (or Peterheid Prison to you and me), to work with inmates and encourage them to be proud of their native tongue, rather than cursing it for making them sound unsophisticated.

“Gaelic has been brought to its knees because people stopped speaking it,” said Alistair, “we can’t let Scots go the same way.

“I have a pal who teaches at a school in the Mearns and recently she was teaching Lewis Grassic Gibbon’s novel Sunset Song.

“She said the kids were complaining heavily – and their parents even started complaining too – because naebody in the class understood Scots, and that is five miles from where the book is set and written.

“There’s places where Scots is definitely taught to bairns at hame in the same way it has been for generations, but there’s loads and loads and loads of folk that are in their 30s or 40s and haeing bairns for the first time themselves but arna passing it on.

“And that is how a language dies out.”

Far dis Scots come fae?

(Where are the origins of Scots?)

Despite being recognised by both the UK Government and the EU, speculation over the legitimacy of Scots as a language continues.

The biggest point of contention is Scots’ seemingly close links with English. And it’s true, many of the same words appear in both languages albeit often with different spellings.

But opening the history books certainly offers a few answers.

The cosy relationship is explained by the fact that both languages descended from Anglo-Saxon, or Old English.

Yet the pair were never identical, with Scots descending from Northumbrian Old English, while standard English traces its roots back to the London area.

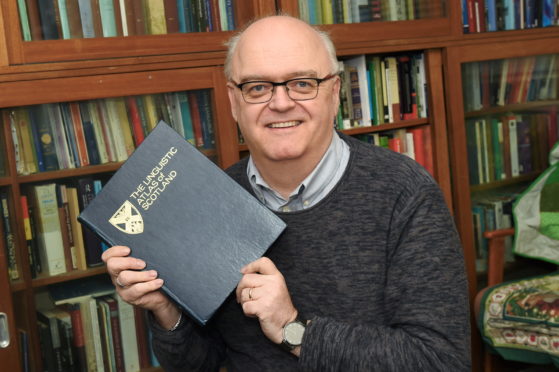

“It (Scots) is a close relative of standard English, but the split between the two goes back more than 1,000 years,” explains Robert McColl Millar, a professor of linguists and Scottish language at Aberdeen University.

“They were already distinctive then and got more and more distinctive,” he said, particularly as travel was rare and Scotland was somewhat isolated.

The invasion of tribes from the European mainland introduced more linguistic diversity, and with a dash of Scandinavian and hint of Dutch now in the mix, a new language began to take prominence north of the border: Scots.

By this point the language had spent centuries developing separately from English, and if this had continued Scots would likely have continued changing to become its very own, very distinct language.

But a convoluted succession of royalty changed everything.

Modern day Scots has no standard form, so each of the dialects are strikingly different from each other,”

Robert McColl Millar

Along came James Charles Stuart, son of Mary, Queen of Scots, who became King James VI of Scotland in 1567 at just 13 months old. Thanks to royal intermarriage, he was also the great great grandson of King Henry VII of England.

As he ascended to the throne, all of a sudden the individual identity of Scotland was dealt a major blow.

After the 1707 Act of Union which created the United Kingdom and the shift of political power to England, the use of Scots was discouraged by many in authority and education, as was the notion of Scottishness itself

English was suddenly the language of the church and the state, and many well-off gentry in Edinburgh took to learning English.

Though now regarded as inferior, Scots remained the vernacular of many rural communities and the growing number of urban working-class Scots, which perhaps explains the language’s blue-collar connotations today.

“Modern day Scots has no standard form, so each of the dialects are strikingly different from each other,” said Robert.

“But once you tune your ears in, you see there are plenty of similarities there too.”

It doesn’t take long for languages to change, he explains. “Just 60 years ago, people in the north-east of Scotland universally said ‘hoss’ as in ‘moss’ instead of ‘hoose’ like ‘loose’, with the ‘oo’ sound at the back of the mouth.

“Now you’d have to go deep into rural Moray before you heard that.

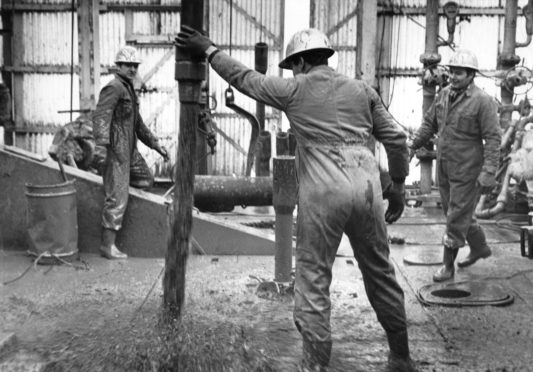

“This change was slowly spreading from central Scotland over a couple of hundred years, but it seems to have jumped in the 1970s from round about Dundee to right into Aberdeen City.

“In my view that’s probably got a lot to do with the oil boom.”

It makes sense. Movement between cities was becoming easier, so when traditional industries like shipbuilding began dying out in the central belt, whole families moved north to places like Aberdeen to seek work, most notably in oil.

This brought with it a change in language. For example in the north-east, ‘what’ would have traditionally been ‘wit’, but this has morphed into ‘fit’ thanks to the influx of west central voices in the region.

But it works both ways; although the north-east’s strong industry attracted many new voices to the area, it is also one of the reasons Doric has remained so distinct.

“One of the reasons north-east Scots is so distinctive and so connected to its Doric heritage is because until very recently a large majority of the people worked in agriculture or fishing, or in the auxiliary trades surrounding it,” said Robert.

“Compare that with places like Glasgow and Dundee, which have altered completely in terms of their makeup and what people do for a living in the last 200 years, and it means that a lot of words were lost because these cities had to become more innovative.”

‘Barking ganzie’

An example Robert gives of a lost Scots word is “barking”, which refers to a procedure carried out in fishing communities up until the 1950s. Bark from certain tropical trees was boiled up and the liquid which was left was water retardant. This was painted on jumpers, overalls, ropes, lines – everything which was taken out to sea. It was a communal practice and had to be done outside.

“It was a pungent process, to put it mildly,” said Robert. “Everyone took part; fishermen, retired people, children across the community… and people I have spoken to have very fond memories of it being part of their childhood.”

But with the introduction of oilcloth and then plastic, the process of barking was lost and the word relegated to the history books. “Words like a ‘barking ganzie’ (water-repellent jumper) were just not needed anymore.”

Fits aah the fuss aboot?

(Why are people talking about Scots now?)

Losing words here and there is one thing but losing the entire Scots language is quite another.

Here to save the day is an unlikely hero, our young people.

While many of their parents have been busy dismissing Scots as slang and answering the telephone in a posh phone voice, Scotland’s youth appear to have undergone a cultural shift.

It’s subtle yet significant, whereby identifying as Scottish is no longer a source of social stigma, nor discouraged in favour of a more homogenous notion of “British”.

People are proudly proclaiming their Scottishness, with personalities like Lewis Capaldi bringing it to the masses.

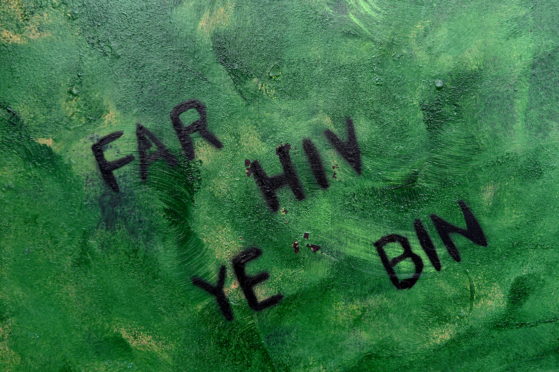

Specific places on social media exist to celebrate the nuances and in-jokes that come with being a young person growing up in Scotland, with hashtags like #scottishpeopletwitter often using Scots language like a badge of honour for those who can understand it.

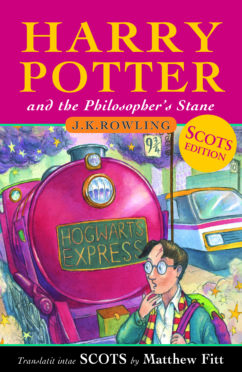

Award-winning children’s book The Gruffalo has been translated into Dundonian, alongside Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stane, while patriotic murals and slick graffiti art bearing unicorns and saltires are appearing all over the country.

Meanwhile Scottish thriller series The Nest and classic sitcom Still Game have reached wider audiences through streaming on the BBC and Netflix. Last year also saw the inaugural edition of the Doric Film Festival in the north-east.

The tide hasn’t just turned for young people either. An online survey with the DC Thomson Media Reader Panel (mostly made up of people age 35 and older) revealed that rather than seeing Scots as a coarse or unsophisticated language, it was associated with positive feelings of pride and identity.

Could it be that being Scottish is finally becoming cool?

Well that might be a bit of a stretch, but 22-year-old Scots singer-songwriter Iona Fyfe thinks we are heading in the right direction.

“You’re not going to get bairns picking up a book of poems by Robert Burns and thinking it’s cool and relevant, because it’s just not,” she said, matter-of-factly.

“But they might just pick up Scots Harry Potter, or even Peppa Pig in Scots, and that’s amazing.

“I’m not losing sleep over traditionalists who think Scots should only be done one way – the old way.

“If we have that attitude it really will die.”

This desire for Scots to be brought into the 21st Century is partly what has inspired Iona’s career.

As a singer-songwriter all of her music is written and performed in Scots, often combining traditional elements of bothy ballads and other Scots-specific musicianship with modern lyrics and arrangements.

Originally from Huntly, Iona grew up speaking Scots at home without realising it.

It wasn’t until she moved to Glasgow to study music that she realised how much she “neutralised” her language in order to be understood by international classmates.

A fiery sense of pride was lit within her, and Iona suddenly saw the value in the language of her community.

“I want Scots music to be modern and accessible,” she said, “for it to be contemporary so people can sing along.

“I don’t want it to be confined to history.”

And her plan seems to be working. Not only does Iona play with her band throughout Scotland, but she has regularly toured south of the border in England, as well as all over Europe in places like Germany, Spain and Poland, educating listeners as she goes.

“I get booked in the weirdest places,” she laughed. “From the Czech Republic to South Australia.

“Sometimes I think people don’t know what they booking, or they are familiar with the idea of Gaelic music so they assume that’s what I’m singing.

“So many folk don’t realise Scots is this third and totally separate living language.”

It’s heartbreaking for me when people ask ‘is it a real language though?’”

Iona Fyfe

However Iona is hopeful that the lack of recognition surrounding the Scots language could soon be about to change.

Along with a group of other Scottish entertainers, writers, academics and political campaigners, she is part of a grassroots campaign which has recently emerged for the tongue to be classified as a “legal language”.

Together known as Oor Vyce, the group are lobbying the Scottish Parliament to pass a law similar to the 2005 Gaelic Language Act, which would give Scots comparable funding, protection and legitimacy within society.

They also want an official body like Bòrd na Gàidhlig, to raise the status and profile of Scots.

“When you think about it, it’s pretty weird to have made a whole career out of a language which isn’t really recognised as a language and has no legal protection,” Iona said.

“It’s heartbreaking for me when people ask ‘is it a real language though?’

“Yes, yes it is. If it wasn’t, people like me wouldn’t exist.”

Dae I ken twa leids?

(Do I know two languages?)

Awareness of Scots as a language might be growing, but speakers remain reluctant to consider themselves bilingual.

However researchers at Abertay University in Dundee have some good news: Being fluent in both a Scots dialect and standard English is as good as speaking two different languages.

It’s all to do with the “switch cost” according to Dr Neil Kirk who oversaw the study.

This measures how long it takes for someone to change from speaking one tongue to another.

Findings showed that the brains of people who are equally fluent in Scots and in English work in the same way as more “traditional” bilingual individuals who speak English with French, Spanish or German.

The experiment was simple; participants were asked to name a series of random objects one after the other in a mix of Dundonian Scots and English.

“We were looking at the speed in which they were able to name things,” said Dr Kirk, a psychology lecturer at the university.

“The faster you can name something, the more dominant you are in that language.

“When you have equal proficiency in English and Scots there is barely any delay in switching.”

But compare that to the monolinguists – volunteers who specifically learned some Dundonian before being tested – and the switch takes longer.

That’s because their brains had to expend more effort suppressing the dominant language and the ‘switch cost’ was higher.

Working with colleagues in Germany, the Abertay researchers also found the same pattern among speakers of minority languages and dialects there.

“There is no definition of what is a language versus what is a dialect that is utterly complete,” said Dr Kirk.

“For example if two people from different places are speaking and can understand each other, you’d assume they’d have different dialects but be speaking the same language.

“And if you can’t understand it, then that’s a different language. But that logic falls apart when you look at places like Scandinavia.”

He’s right; Danish, Swedish and Norwegian share a lot of history and are mutually intelligible, though are not considered to be the same language.

Listening to Scots spoken, as a native English speaker, you might almost feel like you can get it for a sentence or two, and then you’ll have no idea what’s being said for another few sentences, and then you’ll sort of understand part of it again.

“For example, if you have a broad Doric speaker in the south of England,” said Dr Kirk, “it’s likely there’ll be some degree of mutual intelligibility.

“But it could also be that there is just one-way intelligibility, meaning the Doric speaker can understand the English but not the other way around.”

Written, it’s a bit easier, as the sentence structure is broadly similar and some of the vocabulary is shared, if usually altered in spelling.

It’s a complicated subject, but Dr Kirk is hopeful that his research contains an important lesson for Scots as well as an insight into our psychology.

He mentions the 2011 census in which 1.5 million people reported that they could speak Scots, approximately 30 percent of the total Scottish population.

“In a lot of the questionnaires in which we ask people about their language use we’re really not capturing the full story,” he said.

“So a lot of people will report that they speak English and a bit of French or they’re fluent in German.

“But actually they won’t ever consider, for example, their knowledge or use of Scots is worth mentioning on a questionnaire like that.”

Dr Kirk is not alone in believing that Scots speaker numbers may be far higher than officially documented and is keen to see the question repeated in the 2021 census with additional prompts like “Doric” and “Dundonian” to get people thinking.

Fit’s next fir Scots?

(What’s next for Scots?)

It seems that after 300 years of shame, the language of Robert Burns is finally on the up.

For the head of the Oor Vyce campaign, Jack Capener, it’s about time.

“There is little doubt that we are experiencing a real renaissance of Scots,” he said, “possibly for the first time ever.”

At just 23 years old, what Jack lacks in experience he makes up for in passion and enthusiasm.

“It’s gaining more and more prominence in newspapers, literature, theatres, social media… and that is down to the fact that there are a lot of people out there campaigning with their own resources, with their own time and their own money, for the Scots cause,” he said.

“I was one of those people. I’d neglected and pushed aside my own Scots voice when I was younger, but once I rediscovered it I really found pride in Scots again and started using it whenever I could.

“What I thought was really lacking though was a national coordinated strategy – something that links up all these individuals, campaigners and activists and gives them a platform to talk to the government, so I decided to set up Oor Vyce.”

‘The Broons Syndrome’

The goal of Oor Vyce is simple: To gain official recognition for the Scots language.

In Jack’s mind, the most important part of this aim is the creation of an official governmental body which would have the responsibility of looking after, promoting and protecting the Scots language.

Ideally it would be similar to the Bòrd na Gàidhlig, which receives funding from the Scottish Government to promote Gaelic across the country.

But protecting a language isn’t a one-size-fits-all exercise, and success is far from guaranteed.

While the Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act 2005 was a desperate attempt to reel in more speakers of a dying tongue, the biggest challenge Scots faces isn’t a lack of speakers, but a lack of recognition.

This means any act passed by law will likely focus more on getting native speakers to give Scots status and respect, which could prove tricky.

It’s hoped that this will avoid Scots falling deeper into what some experts are calling “The Broons Syndrome”.

Everyone agrees it’s great to see Oor Wullie and The Broons each week, but there are worries that Maw, Paw and the rest of the family paint Scots in a sentimentalised light, and cement the idea that the Scots language is one of the past, relegated to a funny tourist tea towel.

Jack meanwhile has his rose tinted spectacles on, and envisages a Scotland where tourists pack a phrasebook alongside their cagoules and midge repellent.

“It’s really hard to learn Scots,” he says with a smile. “You can’t just go out and take a course on it – there aren’t any courses!”

There are a few things he’s keen to point out, however.

It’s a national project, but not a nationalist one.”

Jack Capener

First and foremost, this is not a “political thing”, he says, throwing his hands in the air mimicking air quotes, “it’s just a Scottish thing”.

What he means by that is that the Oor Vyce campaign is not affiliated with Scottish Independence or the SNP in any way. It’s not a push to distance Scotland from England or “prove” how different citizens are.

“You see a lot of folk online saying that efforts to promote Scots is a nationalist ploy to make Scotland more different from England, and that’s not the case at all,” he said. “It’s a national project, but not a nationalist one.

“It’s already SNP party policy to support the creation of a Scots language board, but that does not mean it is part of government policy.

“The onus is on us as Scots activists to engage with the Scottish Government, and we’ve seen a lot of support from all over the Scottish Parliament, not just the SNP.”

Jack is also keen to set the record straight on something else.

“The drive to recognise and support the Scots language is not about forcing it on communities which don’t feel they have a connection to it,” he said.

The message isn’t “Scots or nothing”, but rather bringing Scots to the fore and teaching younger generations that it’s not something to be hidden.

“We have to acknowledge that Scots is a big part of our world and that should be reflected in institutions like schools and the government,” he said.

It’s difficult to estimate a timeline, but Oor Vyce are hopeful that the Scottish Government will implement changes sooner rather than later.

After all, the seemingly terminal situation that Scots Gaelic has found itself in serves as a cautionary tale, showing what decades of inaction can do to a struggling indigenous tongue.

For Scots meanwhile, native speakers cross their fingers and hope it’s not a case of too little too late.

It may never be a language of business, affluence and splendour, but that’s never what Scots has been about.

Perhaps Lewis Grassic Gibbon summed it up best in Sunset Song, when he wrote that guid Scots could wring and hold the heart, while English words were: “Sharp and clean and true – for a while… until they slid so smooth from your throat that you knew they could never say anything that was worth the saying at all.”

With proper attention and care, lang may the Scots lum reek.

Conversation