The experts

-

Nigel Harris

Managing editor and events director at RAIL magazines – a role he has had since 1995. He has worked in railway publishing since 1981, starting as assistant editor of Steam.

-

Christian Wolmar

Writer and broadcaster whose specialist subject is the railway. He is a former transport correspondent of The Independent and has also written for newspapers such as The Times and The Guardian.

-

Tony Miles

Railway journalist and commentator who has been writing about the rail industry for more than 30 years. He is currently a correspondent for Modern Railway magazine.

-

Roger Ford

The industry and technology editor of Modern Railways magazine and founding editor of Rail Business Intelligence. A qualified mechanical engineer, he has more than 25 years’ experience writing about the railways.

Who decides if trains are cancelled?

Nigel Harris: “It depends on the reason.

“If the infrastructure is in order but the driver doesn’t turn up – that’s an operator issue, so the operator would tell Network Rail ‘this train can’t run’.

“Network Rail could discover a signalling problem and say to the operator ‘this can’t go’.

“Sometimes it’s not a decision – you’re just faced with a reality.

“Whoever had the problem would inform Network Rail control, which operates the infrastructure.”

Christian Wolmar: “Where weather is a factor, a train operations person would be responsible for making decisions around the timetable when there are problems.

“ScotRail and the Scottish route on Network Rail have a closer relationship than on other parts of the rail network because nearly all trains are ScotRail but, whether they have a joint person, I don’t know.

“They would make the decision on the ground.”

Tony Miles: “There are many processes for deciding to cancel trains or related to concerns about infrastructure. I’m sure they would have been followed correctly.

“Safety is the first topic discussed at monthly meetings. It is the thing operators are concerned about the most, because people are placing their journeys in their hands.

“Decisions on whether to run would have been taken very, very carefully.”

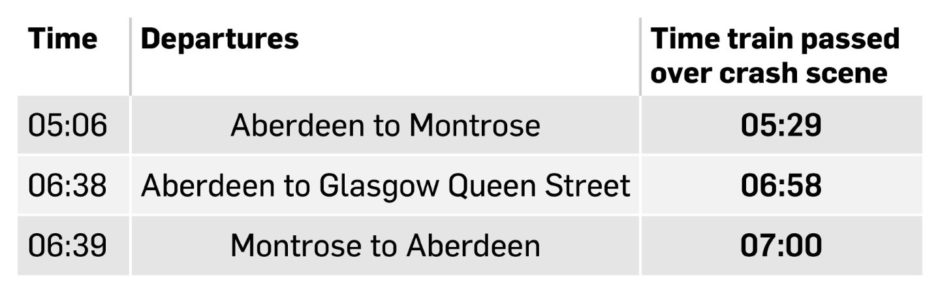

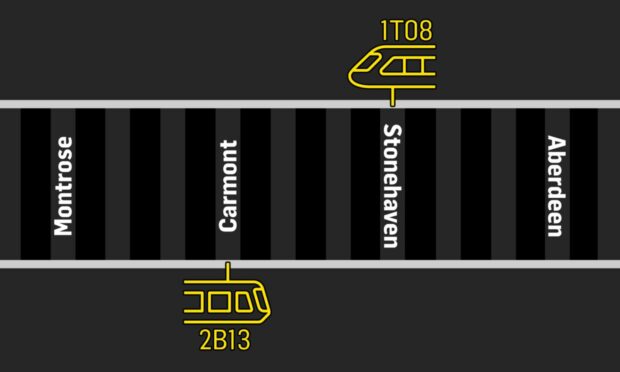

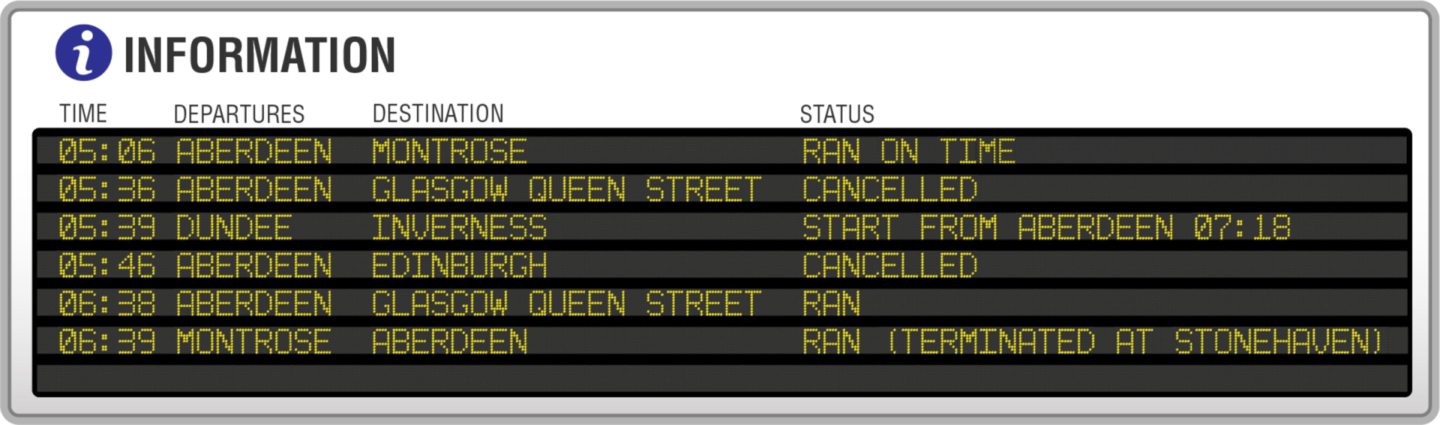

Christian Wolmar: “Just one train had left Aberdeen station at close to 5am.

“You would have possibly had several customers who hoped to get on the two services cancelled around 5.30am.

“Rail workers always prioritise safety but they also have a ‘let’s get the show on the road’ mentality’.

We know two trains were cancelled and one amended due to ‘heavy rain flooding the railway’ – so why is rain a factor?

Nigel Harris: “Rain alone does not cause cancellations, more its impact.”

He added: “It takes a lot to stop a train. Just the presence of a thunderstorm is no reason to cancel.

“The train knows where it’s going, you don’t have to steer it. You’ve got signalling systems that mean trains don’t bump into each other.

“Providing the railway is intact and secure, you can run trains in far worse conditions than you can ever run on a road.”

Christian Wolmar: “Presumably, the trains that didn’t run – staff weren’t concerned about a landslip, but were worried the intensity of the rain would prevent them getting through.

“Just because of a thunderstorm in the area, trains don’t necessarily stop. Trains are pretty robust.

“This is an important service when it gets nearer Glasgow so to cancel it you’re then inconveniencing a lot of people further down the line.”

Why do thunderstorms cause particular problems?

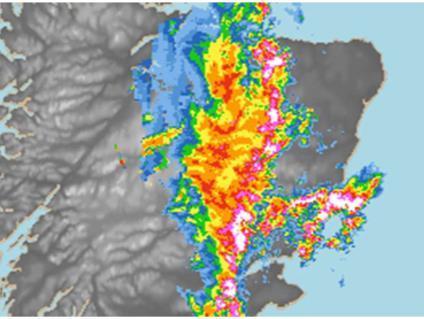

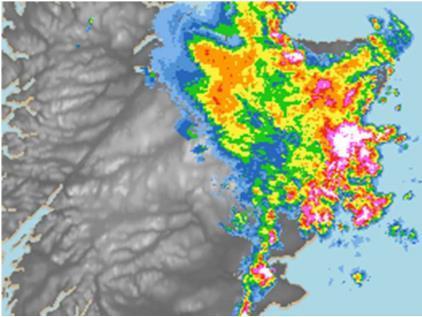

The Met Office had issued a weather warning covering most of the north-east from midnight until 9am on the day of the crash.

It was an ‘amber’ warning – the second-most serious on a three-point scale – meaning it is quite likely bad weather will affect people and they should be prepared to change their plans.

However, predicting exactly where a thunderstorm will appear is difficult.

Met Office spokeswoman Nicola Maxey said: “I’m sure everyone has been sat at home one day in torrential rain while someone in the next village over is basking in sunshine.

“It’s just because these weather features are quite small, it’s difficult to pinpoint.

“We can say ‘this area is at risk from thunderstorms because of the atmospheric conditions’.

“But it’s a bit like – you know a pan is full of boiling water, but trying to work out where the bubbles are going to come up within the pan is very difficult.”

Why is it difficult to predict where thunderstorms will be? pic.twitter.com/r24Ap5yGTT

— Met Office (@metoffice) July 27, 2018

This problem is illustrated by one decision taken on the morning of the tragedy.

By the time the 5.39 Dundee to Inverness service was about to depart, it was relatively dry in Aberdeen but there were thunderstorms in Dundee.

Rail authorities cancelled part of the service and started it from Aberdeen at 7.18am assuming that, because it was dry in Aberdeen when they made the decision around 5.30am, the risk of flooding there was much lower.

But by the time that amended service was ready to roll out of Aberdeen station – at 7.18am – the thunderstorms had reached the Granite City – something the bosses would not have been able to predict at 5.30am.

Why was the train that crashed allowed to leave?

This a question posed by loved ones of the victims and union officials.

In the hours after the crash, Salina McCullogh, the sister of Brett, who had been driving the train, posted a message on Facebook, addressing ScotRail.

She said: “During one of the worst storms to hit Scotland, you sent my brother out to drive a beast of a train”.

Later, Manual Cortes, general secretary of the TSSA union that represents some rail staff, told us: “There were some inconsistencies on the day because some trains were cancelled and some weren’t.

“Why was this train circulating when most other services in the Stonehaven area had been cancelled?”.

Was there a good reason to cancel it?

There are two schools of thought among the people we have spoken to.

One way of thinking is that it is irrelevant because the crash happened almost three hours later; the other way of thinking is that two other trains had been cancelled that morning and allowing this one to run set off a chain of events.

The decision was taken around 6.30am – eight minutes before the train was due to depart.

As the previous two trains had been cancelled due to ‘heavy rain flooding the railway’ it is reasonable to suggest rainfall on the route of the 6.30am train would have been considered.

By 6.30am, it was raining everywhere in the north-east save for Fraserburgh and Peterhead, but there was a sharp contrast in severity.

Up to 16mm fell in south Aberdeenshire in the 30 minutes between 6am and 6.30am compared with up to 4mm in Aberdeen.

The operations manager might not have been aware of how heavy the rain was in south Aberdeenshire or may have thought that, because the thunderclouds were moving north-east, the train travelling south-west would eventually clear it.

Staff at Aberdeen station also had a lack of first-hand information.

By 6.30am, nobody had seen the route for more than an hour: The last person to see it was the driver of the 5.06am service to Montrose, who experienced no problems.

Nigel Harris said there has previously been no reason to inspect the line – but that climate change is increasing the number of severe weather events, and so getting ‘eyes on’ will become a routine in future.

He proposed a solution to this.

Mr Harris said: “If Network Rail wants to ‘have eyes’ on a particular piece of railway, a mobile operations manager has to get in his four-wheel drive, drive in his field to a crossing and walk and have a look.

“If you can put a drone in the air, you can look at a lot more railway much more quickly much more effectively, so there is a new technology solution there to establish whether a line is clear.

“If you’ve got half a dozen men with drones operating up and down the railway when you have got rain like we’ve talked about – within an hour, they can not only prove the line is clear, but by remaining on site and flying the drones up and down you can effectively patrol the line and ensure accidents don’t happen.”

The staff who allowed the 6.38am service to leave were not alone in making that judgement call – as the 6.39am service from Montrose to Aberdeen was also allowed to leave.

Indeed, it was the driver of that service who notified colleagues about the landslip on the southbound side of the line.

Those who have studied the crash remain divided about the significance of the 6.38am service being allowed too leave Aberdeen.

Kevin Lindsay, organiser in Scotland for the Aslef union, which represents train drivers said: “Leaving Aberdeen wouldn’t have necessarily been a problem.

“When that train ran, it got stopped as per the rules and regulations. It was the return journey back north that was the issue.”

Nigel Harris: “To suggest there were trains cancelled earlier and, therefore, they ought to have maybe cancelled this one and (then ask) ‘did someone make a wrong decision? It’s not really appropriate.”

Christian Wolmar: “I don’t see how you can ascribe any blame for making decisions around whether these trains ran.”

Mick Hogg, organiser for the Rail and Martime and Transport workers union (RMT) said: “It’s an operational decision to depart trains.

“I can’t really comment on the decision. Hindsight is a beautiful word.

“If we could turn back the clock – absolutely, don’t depart. Our members would still be alive, as well as the passenger.

“With hindsight, I would never have allowed the train to depart Aberdeen, but that’s just a personal view.”

Mr Cortes believes it is a pertinent question.

He said he has written to the Rail Accident Investigation Branch’s chief inspector Simon French to ask the question and added that Mr French had assured him the question was valid.

The RAIB’s report will address this question when it is published, though that might not be until next summer.

Was it a blessing so few passengers were on board?

ScotRail has revealed that 20 people are typically board the train – 13 more than on the day of the derailment.

Tony Miles: “It was a good job it was a lightly loaded train. For once, the impact of coronavirus was good.”

Christian Wolmar: “It’s a small mercy. If there had been more people on the train, there might well have been more serious injuries or fatalities.

“You only have to look at how the train ended up. Some (sections) of it weren’t survivable.”

What happened at the signal box?

Four parties were involved:

- The driver of the 6.39am Montrose to Aberdeen train who raised the alarm about the blockage on the southbound line, before continuing on his way and exiting to the conversation

- The driver of the 6.54am Aberdeen to Glasgow train, Brett McCullough

- The signalman at Carmont signal box

- The control manager

Roger Ford: “Control would have told the driver to return to Aberdeen.

“The driver would have contacted the signaller by radio, the signaller would have said ‘come here, we’ll put you over to the other line, but we’ve got to wait for the mobile operations manager’. That’s standard procedure.

“The mobile operations manager had to clamp the points so they aren’t pushed apart by the train. The signalman can’t do that.

“(Two hours or more) is a usual time period for him to arrive.

“The train would have been going ‘backwards’, through the points, onto the down (northbound) line.

“When the train cleared the points, it then set off northwards. By then, the weather was sunny and fine.

“There was no sign of a slip at that time (around 7am), so the landslip must have happened in that two-and-a-half-hour period.”

Tony Miles said staff would have also considered continuing towards Glasgow.

He added: “There were probably quite a lot of discussions between the driver and the signaller like ‘what are the best options here?’

“There may have been a discussion – and we won’t know until the voice records are released – that the flooding ahead of the train (on the southbound line) might have dissipated and it would have been safe to move forward.

“That would have been less inconveniencing for passengers than moving backwards.

“They may have said ‘before we decide to reverse, we’ll just wait to see if conditions improve enough to carry on’.

“If they decided to carry on southbound, they may have advised him to go at 5mph and look ahead and, as soon as he spotted anything, to stop and report it.

“Or he might have been able to report ‘look, okay, it’s clear for me to complete the journey but I think we’re going to need some inspection before anything can go over it any faster’.

“The drivers are used to being asked if they will do an inspection at very low speeds.

“Once they decided to go back towards Aberdeen, the signaller would have given the driver permission to reverse back and cross the line and say how fast he could go when crossing and whether he could go onto full speed when he got onto the other line again.

“The driver would have to repeat all that back, as is proper protocol, so both understand the information they are sharing.”

Nigel Harris: “Network Rail will occasionally send a live engine out before services start to make sure the line is clear, but that wouldn’t have helped in this incident because, the place where the accident occurred, Brett McCullough had passed two hours earlier and the line was clear.

“According to all the operating practices in place at the time, neither the signalmen at Carmont nor Brett McCullough had any reason to believe the line was obstructed.

“That being the case, we were overtaken by events very quickly after the passing of the train that left Montrose for Aberdeen at 6.39am.”

What assessment can be made of the train’s speed before it derailed?

This is the question that has provoked much controversy in the aftermath of the tragedy.

An RAIB report published on August 21 said the train was travelling at 72.8mph.

Several media outlets reported on this, causing anguish to Mr McCullogh’s loved ones.

Afterwards, his widow Stephanie, said: “Brett did everything by the book.”

The experts agree.

Nigel Harris: “Brett did nothing wrong.

“In order for a train to keep to time, it has to run at line speed.

“Line speed is not the speed limit – it is the speed a driver needs to aim for in order for the train to run to time.

“The fact he got it to 72.8mph when the speed limit was 75mph isn’t an indication that he was pushing his luck – it’s an absolute hallmark of his professionalism.

“Paramount in Brett’s mind would have been ‘I need to get these people back to Aberdeen within the minimum of delay now’.

“He would have talked to the signalman at Carmont. If there was a need to do so, the signalman would have cautioned him about the necessary speed.

“Everyone concerned seems to have done entirely the right thing and there is nothing to suggest the line was anything other than clear and that Brett McCullough was doing a thoroughly professional job to get the passengers back to Aberdeen with minimum further delay.”

Some people may think he was going too fast – that is certainly not the case.”

Christian Wolmar

Christian Wolmar: “You will have miffed passengers on the train who have been sat there for several hours and are now going in the wrong direction.

“It’s not the driver’s responsibility (to determine the speed).

“He is controlled by the signallers who are in turn controlled by the controller.

“He is under orders and he has no reason not to go at line speed unless he’s told to do so.

“He is not in a position to judge what the conditions of the line are further up the track.

“Some people may think he was going too fast – that is certainly not the case.”

What factors contributed to the derailment?

The experts believe the crash was caused by a lethal combination of a freak amount of rain, the curve on the track, the presence of the bridge and the location of earthworks where a relatively significant amount of work and inspection had taken place in the last 20 years.

Christian Walmer: “That is a very good summary. All those things played a part. Take away one and the crash doesn’t happen.

“If the bridge wasn’t there, the train would have shuddered to a halt.

“It’s sad to say – but these horrendous things do happen.

“As ever with these accidents, there is a series of decisions leading up to it where, any of those decisions being made in a different way could have prevented it, but that’s not to say it’s anyone’s fault.

“We’ve had bad luck. We’re looking with hindsight.”

Nigel Harris: “The planets came into alignment in a very bad way.”

“If this had happened on a straight section of track, all that would have happened is everybody would have got a jolt and a shock and the train would have come to a standstill upright.

“The fact that it happened on a curve – and at a viaduct – it has stripped the wall off the viaduct and toppled down the embankment.

“Unless RAIB finds something, I can’t see any evidence that anybody made a dodgy decision.

“I’ve seen nothing yet to suggest someone made a bad decision – quite the contrary.”

Tony Miles: “After this crash, a lot of people have asked ‘whose fault is it?’ I suppose that has happened because fatal rail crashes or derailments are so rare.

“It’s going to come out as an Act of God.

“It’s a combination of the ground doing what it shouldn’t and the laws of physics – heavy metal moving very fast.

“Sometimes people do things with the best intention. For example, deciding to take the train back (northbound) was the right decision.

“I think it will come out that they had the right conversations with colleagues.”

Roger Ford: “If the train had been going the other way and hadn’t hit the bridge, this would have been a minor incident.

“It’s harsh to say but, when it’s the first fatality on the railway since 1995 (caused by a landslip) it’s terrible for those involved, but you can never promise it won’t happen again.

“If you balance the equivalent of a jumbo jet on wheels resting on thin steel rails and run them fast, there is always a risk something can interrupt it.”

Manual Cortes: “Sadly, an extreme weather event appears to have caused the derailment of this train.

“So what is badly needed is additional investment to make our railways more resilient in the face of this.

“I’ve called on the Transport Secretary Grant Shapps to give cast-iron guarantees that this investment – the money that is required to make our railways more resilient in the face of climate change – will be made available.”

Nigel Harris: “It looks like an awful example of extreme weather, and the impact that had on the drain.”

Kevin Lindsay: “It’s too early to say if there have been any systematic failures (with the derailment) and if anyone should be held accountable for it.”

“I don’t want to comment on specifics around Carmont because the RAIB and Police Scotland are doing an investigation. It would be speculation at this stage.”

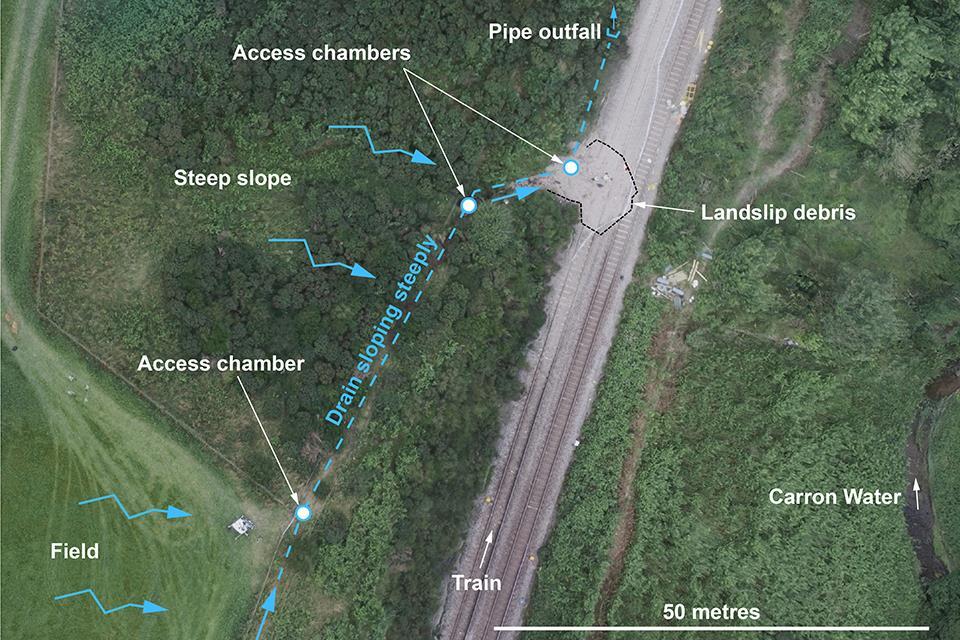

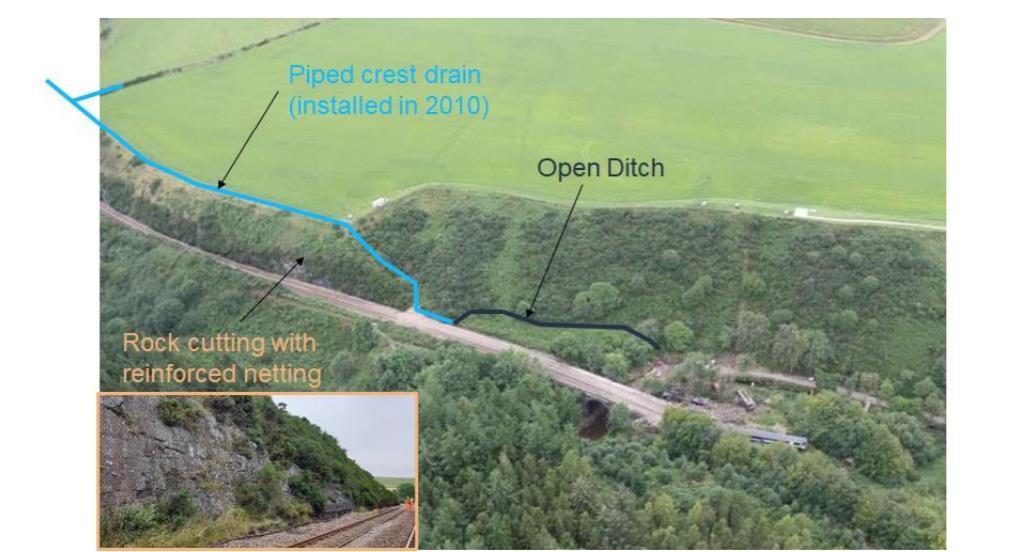

What do we know about the drain?

At the site of the derailment there is a steep slope leading down from a field that could cause lots of rainwater to flood the rail line, if left to nature.

To prevent this, Network Rail installed a drainage system. This system was replaced in 2010, taking rainwater from the field and the slope down into the river below the rail line.

Nigel Harris: “The drain is 18in in diameter. It is a big drain.

“In 2010, that would have been calculated by the civil engineers to be adequate for the worst rain that could fall. Network Rail was on the ball.

“But things have changed. Extreme weather has become more frequent and severe. The drain has become unsuitable to take the water it was designed for.

“They must have had something which told them there was a risk of that embankment washing down onto the track, so we need to put a drain in – and that’s what they did, with the size required for the envisaged maximum load put on it.”

Roger Ford: “In 2010, Network Rail spent well over £1.8 million on doing a hell of a lot of work, by putting nets in at the rock cutting (next to the derailment site).

“They put the drain in on the top and down the side.

“You put the perforated pipe in, then you bed it down with gravel.

“On the morning of the derailment, the flood of water coming down off the fields just passed the rock cutting washed the stone and the gravel out of the trench.

“The water came down and just overwhelmed the drain.

“You wouldn’t expect a flood of water heavy enough to wash gravel out of a trench and stones out of a wall by the side of the trench.

“There is no way you could have expected that or monitored it. It’s a very rare occurrence but every now and then it goes wrong.

“These are things that you cannot allow for.

“It was fairly minor landslip, as landslips go, but it was just fatal.”

Tony Miles: “The fact that the drainage was most recently inspected in May 2020 (with no defects recorded) shows how fast things can change.”

Could Brett McCullough have reacted quicker?

No. The experts unanimously agree.

One rail industry insider, who asked not to be named, said: “I spoke to a train driver who transported the cranes to the site so they could be used to recover the carriages.

“He just said ‘I can understand why the driver would have had no time to react. If I’d have come round that corner driving that train I virtually wouldn’t have had time to do that instinctive thing you do to put the brake on.

“It is quite a tight bend. He understands why there was little time to do anything.”

Tony Miles: “The time to react would have been almost non-existent. It takes half a mile or a mile to slow down.

“People initially were saying ‘why didn’t the driver just slam the brakes on?’ But the laws of physics mean it takes a long time to stop.”

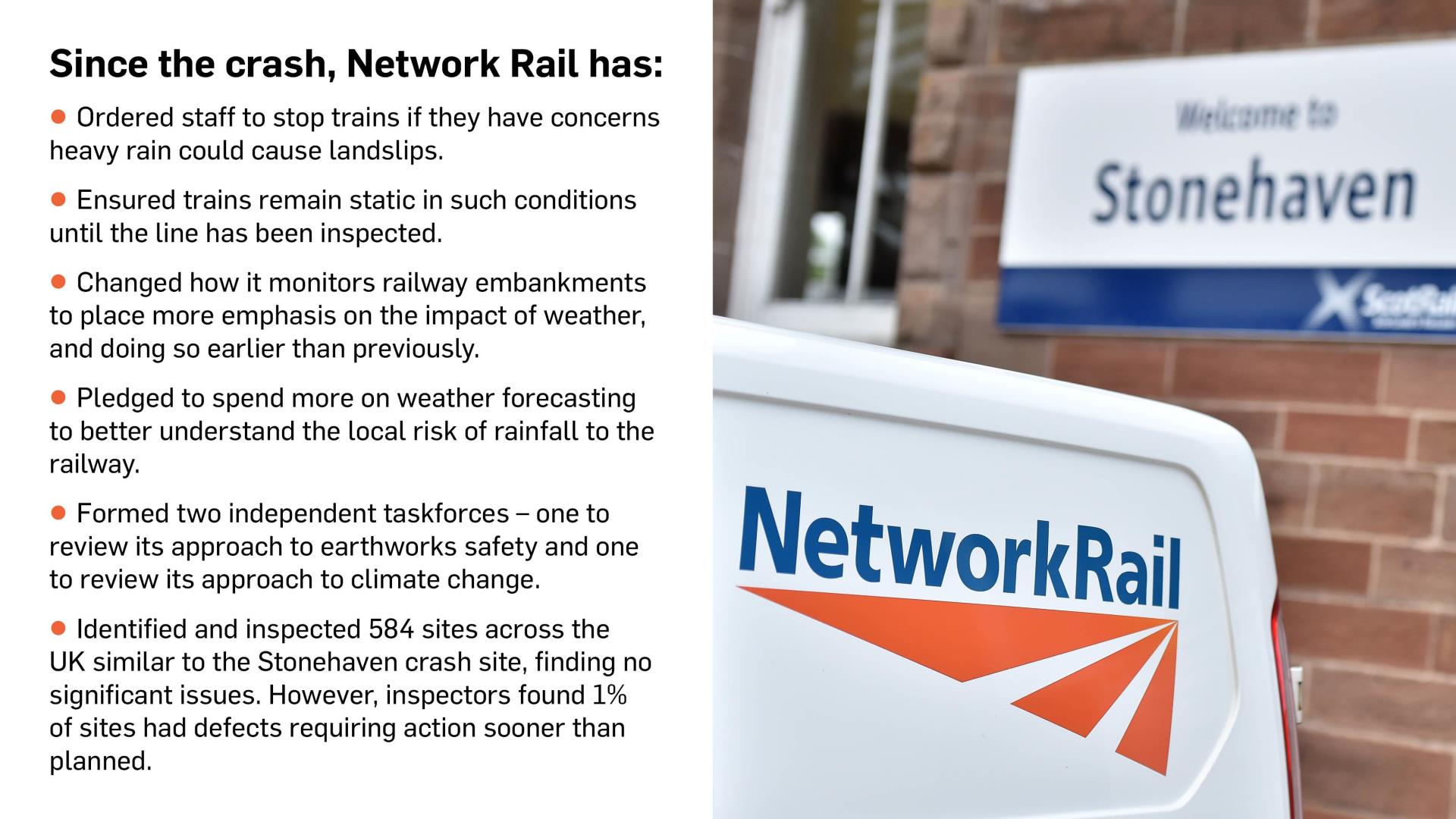

What practical steps has Network Rail taken since the derailment?

Immediately after the derailment, UK Government Transport Secretary Grant Shapps ordered Network Rail to write a report detailing what the derailment might mean for the resilience of the wider rail network.

That report was published on September 1.

It said that Network Rail issued an emergency instruction on August 18 to remind staff of the need to report concerns related to weather and landslips.

Perhaps most significantly, the instruction said: “…where there is a potential for infrastructure damage…all trains are stopped until the infrastructure is inspected”.

On September 5, Network Rail strengthened rules relating to instructions of trains operating during extreme weather, including where there is a risk of earthworks failure.

It also improved weather guidance “to determine the appropriate response to implement during adverse and extreme weather”.

Within 16 days of the derailment, Network Rail had identified and inspected 584 sites across the UK “which share some characteristics” of the crash scene. No significant issues were detected and defects found at 1% of those sites will be repaired sooner than planned.

What do the experts think of that action?

Manual Cortes: “The point about line inspection seems very sensible to me.

“If you’ve had atrocious weather and, let’s face it, this is how the weather was described on the day, and you’ve already cancelled a number of services, it stands to reason that, before any services are allowed to run, that there should be a thorough investigation to ensure that the infrastructure is in a position to support train movements.

“It is better to err on the side of caution because, ultimately, a train derailment can cause a lot of casualties.”

Kevin Lindsay: “Network Rail has already implemented rulebook changes.

“Drivers now have to report water on tracks right away and stop their trains. Is it kneejerk? That is for the industry to judge.

“Everyone is questioning everything now. Our safety reps and our industrial reps are doubling down on everything they do to ensure the job is as safe as possible.”

Tony Miles: “There are stronger rules in place now when there’s bad weather as to what discussions should be had between staff and even more strict rules on asking drivers to check the track than there were before.

“They will want to learn every lesson possible so at least out of this tragedy something positive comes from it.”

Roger Ford: “It is commendable that they have made these changes, but it’s important to remember Network Rail was already doing a great deal of work on this and we won’t know the full picture until the final RAIB report comes out.”

Nigel Harris: “Between 2014 and 2019, Network Rail had already doubled the money spent on earthworks. Everyone was on the case.

“But the situation has changed and worsened more rapidly more than anyone could have envisaged.

“Brett McCullough tragically ran into one of those areas where it has gone beyond what the system could take.”

Mick Hogg: “Network Rail has done a good job in the way that it has reacted and working together with unions.

“As a result of the incident, there are going to have to be lessons learned.

“Because the railway goes way back to Victorian times in terms of infrastructure and drainage, that tells me that potentially, what has happened at Stonehaven could potentially happen again. That phrase absolutely horrifies me.”

What else needs to be done to make the railways as safe as possible?

Nigel Harris: “There needs to be a focus on how thunderstorms can be managed.

“We are, to a degree, in unchartered territory.

“We’re in a time when we’ve got sudden, very vicious extreme weather where you can get a month’s rainfall overnight.

“RAIB and Network Rail will be looking at this. It will be one of the key aspects of the RAIB investigation

“Network Rail was working according to protocol. We must ask if the protocols need to change.

“The RAIB investigation has now got to ask: ‘What procedures do we need in place given when we are getting extreme weather that can cause landslips within a very short period of time?’”

He added: “If the window of time in which weather can do damage has become shorter the railway needs to find new ways of monitoring the line, hence the idea about drones.

“The mobile operating manager at Inverness (recently) asked if he could be trained on drone use because you can look at a lot more railway much more quickly and effectively than by driving. Perhaps that is a solution.”

“Also, if you’ve got a piece of railway which has got a history of being unstable, you can put GPS markers in the embankment or cutting side and, if they move, they sound an alert which can stop a train.”

Mick Hogg: “The idea of deploying drones is good – providing you’ve got perfect weather. I’m not sure if they would work in adverse weather or the dark, but they are a good bit of kit.”

Tony Miles: “It might be where there has been heavy rainfall in an area close to a possible landslip area the instruction to the driver is to proceed at 30mph and inspect the track.

“If protocols are tightened up on the basis of what’s happened after the accident those will be new steps to make things even more belt and braces than before.”

Mick Hogg: “Learning the lessons of what has happened at Stonehaven may include rail staff being extra vigilant.

“If that means holding trains at stations or at certain points while checks take place during severe weather, that’s a good thing because you’re double-checking the infrastructure is okay, there’s no landslides and the train is able to get from A to B.”

The big challenge is monitoring these sudden slips, which can happen in seconds.”

Roger Ford

Tony Miles: “Weather resilience work was already happening before this derailment.

“Network Rail was in the process of making the case to Government for the necessity of this work because of the environmental situation and because there has been an increase in minor landslips.

“In the shorter term, the discussions they will be having will be around getting advanced warning of heavy rain where there is a potential for flooding.

“They may consider improving drainage and land movement, where you install a little black box at particular sites, which monitors when land moves and sends out an alert when that happens.

“In the longer term, it may involve having discussions with those who own the land near to particular rail lines, about how that land is managed to improve drainage.”

He added: “Technology is already there, but maybe needs to be used more.

“There are trains now around the country that monitor the track as they are travelling.

“They can report ‘there is a bump there that wasn’t there yesterday’. It may only be a tiny defect but if that happens more often, it may well be monitoring needs to be stepped up. That’s all part of the learning curve.”

Roger Ford: “There’s lots of ways of mitigating problems at potential landslip sites but, when you realise there are something like 20,000 relatively low-risk sites like the crash scene, it’s difficult.

“You get a sudden landslip, which can easily happen, so that is a risk that is always going to be with us.

“The big challenge is monitoring these sudden slips, which can happen in seconds.”

Are there any suggested improvements that won’t work?

In its resilience report, Network Rail suggested making trains slimmer or installing unused ‘check rails’ to offer trains more protection from landslips.

Nigel Harris: “It would be impossible in terms of cost to create a flood plain alongside every piece of railway. That’s just ludicrous.”

Kevin Lindsay: “Cost is going to come into it. We’ve just got new electric trains in Scotland.

“They are not going to be replaced for at least 25 years. The next new trains in Scotland are probably going to come in 10 years’ time.

“It’s fanciful to think that that’s going to prevent any rail crashes in the near future.

“They are talking about the idea of building a third rail – the cost of that is huge when you consider Network Rail is saying it is impractical to rebuild thousands of miles of earthworks due to funding. Where are they getting the money for this?”

The possibility of introducing speed limits during heavy rain for trains travelling on curved sections of train near bridges was also rejected.

Tony Miles: “There are tens of thousands of places where embankments would need careful management.

“There are curves on tracks all over the place so, if you did it for everywhere, you’d need to physically put signs in place and provide written information for drivers.

“The driver would also have to be taking his eyes off the line more to check every bit of instruction, perhaps half a mile a part or a mile apart, which means he’s not looking ahead.

“You add the stress to his concentration, of trying to flip between many things.”

Was the model of train crashworthy?

This is one of the issues that has divided the industry experts and officials.

Speaking to us in the aftermath of the derailment, Manuel Cortes questioned the crash worthiness of the train’s carriages – all Mark 3 models – in comparison to newer trains.

British Rail entered Mark 3 carriages into service in 1975.

They had been used by Great Western Railway and were then refurbished before being given to ScotRail in 2017.

Mr Cortes told us: “When I wrote to Simon French I also did raise issues around the crashworthiness of a 40-year-old train versus some of the new rolling stock that we now have on our railways.

“I was quite taken aback when Scotrail announced they were bringing in this new train. I called them museum pieces.

We’re using 50-year-old trains, so if that constitutes the best railway Scotland has ever had, God help us.”

Mick Hogg

“On the same week Scotrail announced that they were going to be refurbishing a number of sets, Great Western donated three to a museum.

“There must be an issue, I think. That’s why I asked the question (to RAIB) of whether or not the crashworthiness of this train is robust enough when you compare it to a more modern model and I hope the investigation will answer that question.”

Mick Hogg: “Mr Cortes is bang on the money. We keep getting reminded from ScotRail that we currently have the best railway that Scotland ever has seen.

“It’s a million miles away from the best. I would go as far as saying it’s the worst.

“We’re using 50-year-old trains, so if that constitutes the best railway Scotland has ever had, God help us.

“It’s nothing more than an absolute shambles.

“We should never ever be using these trains. We should have a railway that is up there, fit for purpose and reliable with good trains that have been recently built.

“It is an absolute joke we’re using those trains and the quicker we get rid of those trains the better.”

However, the others believe this view is misplaced.

Nigel Harris: “The operators whose trains travel fastest and cover the most ground get the newest trains and, when a newer model comes in, the older ones are given to an operator with less demanding routes.

“That has been going on since George Stephenson invented railways.

“It is known as a cascade. You put new carriages in at the top, and cascade the older ones down.

“After the Mark 3s did 40 years of solid service at 125mph, a new fleet of trains was brought in at Great Western, so the Mark 3s were retired.

“They were then refurbished and given to ScotRail.

“ScotRail should be commended for taking that express fleet of carriages, refurbishing them by putting in new safety aspects like sliding doors and putting them back to service at a much lower speed.

“They have done billions of safe miles and has got a fantastic safety record but this derailment was way beyond the design specification.”

Explaining why the Mark 3’s design is robust – but was to its detriment on the day of the derailment, he added: “The Mark 3 is a very strong, tubular, construction.

“It has got incredible end-to-end strength.

“Imagine a tube in the middle of a toilet roll. If you put it between your hands and try to squash it, it’s not easy to do – a Mark 3 is similar so it withstands frontal impact well.

“Mark 3s tend to hold up in line and upright even when they come off the tracks.

“But in this instance, a carriage has landed on top of another.

“With a toilet-roll tube, if you put your hand on top and try to squash it, it’s very easy.”

Tony Miles: “Considering the speed it was going and the physics involved, the train still stood up remarkably well compared to a car or a coach on the motorway.

“You’d be very lucky to have survivors if it was a coach.”

It is understood RAIB may carry out a computer simulation of the derailment as part of the investigation, seeking to understand the crashworthiness of the Mark 3.

Nigel Harris said he does not believe the Mark 3 needs to be taken out of service or redesigned.

He added: “You get the occasional instance where the force placed on the carriage goes way beyond even the safest design.

“However strongly you build something, you cannot make them indestructible.”

Could the recovery effort have been quicker?

Experts have revealed that those working within the rail industry were frustrated by the amount of time it took to start track repairs and get the line reopened.

Their view is there is a double standard between how road and rail crashes are dealt with – and the slower handling of rail incidents peddles the myth that the railway is less safe than the road.

One expert, who asked not to be named, said: “There was a rail worker whose job it was to drive a train carrying cranes to the site to be used to lift the derailed carriages.

“He sat in the train saying ‘I don’t understand, it’s the third day in a row I’m just sat in a cab waiting.”

Tony Miles: “There was annoyance within the industry that the legal process hampered the recovery as much as it did.

“(Rail workers) are saying ‘why, when a coach crashes into a bridge, the first thing they do is drag it out of the way so the road can reopen but on the railways, they leave it 14 days before they start touching it. Why the difference?

“That didn’t happen in the 1980s. They would get the line running much quicker then.

“There has been a strong reaction (among rail workers).”

He added: “Had (the emergency workers) felt there was somebody alive underneath it all, they would have found a way to lift it very quickly. But once they established they weren’t needing to rescue anybody, they then didn’t want to move anything at all.”

People mustn’t lose sight of the fact that rail is an incredibly safe form of transport.”

Tony Miles

Roger Ford: “They were on that site for a record amount of time. They were doing fingertip searches after the vehicles were lifted. What they have been looking for? I don’t have the first idea.

“The police were on there. Network Rail workers had to be accompanied by police.

“It was considered a crime scene and it wasn’t handed back (by police) until many days had passed.”

Work began on moving the train from the site on September 10 – 29 days after the tragedy – and the line reopened on November 3 – 83 days after the crash.

Tony Miles: “Investigators were able to establish exactly where the train had gone off the rails and given a report on that within two or three days so, quite why they needed another fortnight (to move the train), makes you ask – is that reasonable?’.

“However, we know the road structure wasn’t capable of taking the load of the train once it had been lifted by the crane, so they did have to improve the road.

“People mustn’t lose sight of the fact that rail is an incredibly safe form of transport.”

Roger Ford: “The idea of it being logistics (and problems getting access to the site meaning the recovery effort was held up) was wrong.

“There’s a road not far away, and you can get a Land Rover there.

“I don’t buy this argument that the site is awkward to get access to.”

Mick Hogg: “Due process has to take its course, it’s absolutely crucial.

“Also I’m pleased Police Scotland and British Transport were able to work together on the rescue operation, so they were able to share expertise.”

Though RAIB has to date published two interim versions of the investigation report, the full report might not be published until July.

Nigel Harris: “It’s a source of frustration that it takes so long to do the investigations.

“They have to be thorough, so that takes a long time. I think it should be quicker because we ought to have reports quicker.”

Tony Miles said Network Rail had a window of opportunity to do any landslip prevention works at the crash scene, from when the line was cleared to when it was reopened.

He added: “If there are any works to do on the embankments at Carmont, the best time to do it was then.

“If they decide they want to cut away the embankment, or reshape it or change the drainage – that period is the time.

“They will have wanted to get the job done properly rather than doing a temporary job and having to revisit it in future.”

Outlining what work could have been done, he added: “If they thought this embankment was more stable than it turned out to be, then it might be good if they have time to dig down inside it.

“If they used the time wisely to learn things out of this sad event, they can learn for the future.”

Tony Miles said that there is always a pay off between the need for caution when running services and people’s expectations that they will complete their journeys on time.

He added: “Behind all of this is the Government, MPs and the general public saying ‘why the hell isn’t my train on time?’

“In winter when there has been severe weather and a tree trunk has gone through the cab of the train and missed the driver’s ears by millimetres, the next day they say the first train will go slowly to check there’s been no further trees have gone down.

“You get some people who say ‘oh for goodness’ sake – the drivers should just man up and go for it’.

“It’s good rail operators are putting videos and pictures out of hazards so they can say ‘look, do you want us to be gung ho or should we be more careful because this is what might be round the next corner?’

“People just need to be minded that it’s better to arrive safe and sound a little bit late.

“People who might be thinking the rail authorities should make it even safer might be the same people who don’t check the oil in their car or tyre pressure every day.”

Tony Miles said there is also a pay off between safety measures and the cost of them.

That was underlined in Network Rail’s network resilience report, published on September 1, which said: “In the short term, rebuilding thousands of miles of earthworks to modern-day standards is not practicable either from a funding or deliverability perspective.”

Tony Miles: “It’s a difficult one. This is obviously an emotive subject, but there has to be a practical perspective.

“If you’re the family of the victims in the derailment, then no amount of money would be enough to protect a life.

“If you’re the general public sitting down being rational in a group and saying ‘look, the railways could spend £15 million more per life that has been lost over however many years, but someone has to pay for that either in taxes or fares – are you happy to pay for that?’ Generally, once you get to a certain value, people will say ‘no’.

“The network was built 190 years ago and Network Rail has now got to convince the two main governments that, even after the pandemic, we’re not going to cut investment and we’re going to spend more on it, to make sure it’s good for another 90 years.”

Kevin Lindsay: “It is worrying when Network Rail comes out with statements that they don’t have money to make the railway as safe as possible.

“They should be letting people know what work needs to take place and then, if there is additional funding required, that can be raised with either the UK Government Department for Transport (DfT) or Transport Scotland.”

Mike Hogg agreed with Mr Lindsay about how wise that Network Rail statement about money was, calling it “defeatist”.

He added: “We know to make the railway totally safe, you’re talking about spending billions of pounds.

“Accidents will happen – it’s all about learning the lessons and putting in place an action plan to ensure, where possible, it doesn’t happen again.”

Mr Hogg said that privatisation of the railways had led to billions of pounds being paid out to shareholders and that it would have been better for passengers had that money been invested back into maintenance.

He added: “Money needs to be reinvested in our railway and the only way that is going to happen is if we end this madness of rail privatisation and get rid of the franchises who are making a mockery of the railways.”

Unions have urged the Dft to guarantee enough funding will be put aside to make any improvements investigators deem necessary.

In an exclusive interview, Transport Secretary Grant Shapps told us: “Network Rail have so far advised us there is sufficient funding within their current regulatory settlement to implement the immediate measures.

“When we are assessing the future funding needs of the railway, we will take advice from Network Rail and the independent Office of Rail and Road on the level of funding required for climate change adaptation and severe weather resilience.”

In the aftermath of the Stonehaven rail crash, Network Rail has established two taskforces – one to look at how climate change may impact rail safety in future years and the other to look at how earthworks.

Kevin Lindsay: “The establishment of the taskforces has got to be welcomed.

“However, there is a question of why now? Why wasn’t it done sooner if Network Rail knew that it had issues with its earthworks?

“Climate change is a huge issue for us and across the world.”

He added: “We need to know if the taskforces are going to report back to Transport Scotland or are they going to go to Network Rail to then the DfT because there is no way of any changes getting implemented without buy-in from Transport Scotland.”

Roger Ford: “The taskforces will be checking the homework of Network Rail. It’s a scrutineering role.”

“I think they will really check what Network Rail is doing, make some recommendations, particularly on the weather side, but I don’t see them having a huge impact.”

Mick Hogg: “The task forces are charged with a variety of challenges and need to make sure those challenges are addressed and fixed within a reasonable amount of time.

“We don’t want investigations going on for years. The families want answers now, not in many years’ time.

“It’s important we move heaven and earth to learn lessons and put in place an action plan to address what happened at Stonehaven and give the families the answers they need and rightly deserve.”